Robert Louis Wilken is widely and deservedly recognized as a leading advocate for patristic theology and its pertinence for contemporary Christian thought (see his The Spirit of Early Christian Thought: Seeking the Face of God, 2003). He is the general editor of this impressive series of patristic and medieval reflections on each of the biblical books. In addition to this volume on John, books on the Song of Songs, Isaiah, Matthew, Romans, and 1 Corinthians have also appeared in print. The Gospel of John offers a good opportunity for assessing the series, since this most “spiritual” gospel was, together with Matthew, the most attractive to ancient interpreters, and received the most and closest attention from them.

John: Interpreted by Early Christian and Medieval Commentators is crafted to provide modern readers easy and rewarding access to the ancient authors. After a short essay by Wilken, “Interpreting the New Testament,” Bryan Stewart follows with an “Introduction to John” that clears the way for the subsequent reading of unfamiliar authors on Trinitarian and Christological considerations, sacramental theology, figural readings, John and the unity of Scripture, John and the Synoptics, and moral applications.

Next comes a selection of “prefaces” to John’s Gospel from various ancient writers, which offer the type of introductions—concerning the author and circumstances of the writing—that are found in standard contemporary treatments. The balance of the book is a chapter-by-chapter collection of interpretations of John. Those familiar with such anthologies will be surprised (and pleased) by three things: first, the selections are substantial and sometimes quite lengthy; second, the range of authors is wide, extending from Origen (185–254) to John Scotus Eriugena (815–877) to John Cassian (360–435) to Romanos the Melodist (490–566); third, selections are drawn not only from commentaries—where little of the juice of ancient interpretation is found—but also from homilies, theological writings, and even poetry. The volume concludes with notes on each selection, a biographical sketch of each contributor, and full indices.

Our patristic and medieval ancestors in the faith scarcely require my recommendation. But this volume makes a strong case that, far from being only of antiquarian interest, those whose lives were profoundly and pervasively shaped by Scripture (in a manner none of us today can claim) and whose faithful witness to the One whose Spirit was at work in all of Scripture, have everything to teach us about both Scripture and the faith. Kudos to Eerdmans for investing in such an expensive—and so constructive—an enterprise.

John

Interpreted by Early Christian and Medieval Commentators

translated and edited by Bryan A. Stewart and Michael A. Thomas

Eerdmans, $65.00, 684 pp.

If proof were required that mystical prayer can cohabit with tough practicality and wry humor, these letters of Teresa of Jesus (1515–1582) contain more than enough evidence to make the case. Canonized forty years after her death by Pope Gregory XV in 1622, Teresa was declared a doctor of the church by Pope Paul VI in 1970. Her works on prayer, above all, The Way of Perfection and The Interior Castle, continue to be read with great profit by those seeking a deeper life of prayer. But the other side of Teresa—the founder of communities, the defender of her movement of reform, the woman who suffered from both physical ailments and powerful human opposition—appears vividly in the letters she wrote, often late at night and sometimes, when especially weak, through dictation.

This collection of one hundred letters (offered in the Christian Classics Series from Notre Dame) is an abridgement of a two-volume edition containing all 342 extant letters and the fragments of eighty-seven others (2001, 2007), also translated by Kavanaugh. They are arranged chronologically, written from when Teresa was in her forties through the last month of her life. The last, written shortly before her death, is filled with advice for the prioress of one of her communities. We hear her, then, at the height of her struggles to secure the physical and spiritual foundations of the Discalced Carmelites.

As she writes to her relatives, confessors, associates, various clerics, and patrons from the nobility, we grasp how very “this-worldly” her efforts necessarily were: acquiring land and buildings for her nuns, gaining financial support, supporting her colleague John of the Cross, appealing for help to King Philip II, discerning which young women with substantial dowries seeking entry to her financially strapped communities actually had religious vocations—all these occupy her attention. At moments, we can almost feel her frustration and longing to be free of such distractions, not least because of the vagaries of the postal system. At the same time, Teresa shows flashes of sardonic humor, a directness in expressing her views of people, and a charming appreciation for gifts of fish, fresh fruit, and sweets.

Each letter in this edition is generously annotated, so that Teresa’s sometimes oblique references are made more clear. Particularly helpful is a comprehensive appendix that provides biographical sketches of all her correspondents. With the assistance of these, the collection offers insight not only into Teresa’s mind and heart, but also into the complexities of ecclesial life in sixteenth-century Spain. So vibrantly alive does she appear in these letters, more than five hundred years since her death, that we’re led to consider just what a powerhouse of the Spirit she must have been in the flesh.

St. Teresa of Avila

Her Life in Letters

Kieran Kavanaugh, OCD

Ave Maria Press, $22.00, 352 pp.

Coming to grips with the human Jesus was a challenge not only to Enlightenment-era Europeans, but also to Asian intellectuals who needed to make sense of the religious figure championed by Western colonial powers. R. S. Sugirtharajah is emeritus professor of hermeneutics at the University of Birmingham and is well known as a proponent and practitioner of post-colonial studies, one of the dominant scholarly approaches in the humanities, not least in religion. The Eastern encounter with the Western Messiah is naturally a textbook case for examining the complexities of cultural collision.

Although Sugirtharajah spends a chapter on earlier periods, his main focus is on Asian writers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries who responded to the political hegemony of Western powers and the missionary incursions of Christians. He notes the great difference between the evangelization of Europe and Asia; while colonialism drove the political and economic dynamics of conquered territories of Asia, Christian missionaries confronted ancient and profound religious traditions that were more than capable of holding their own both intellectually and spiritually.

In texts known as “the Jesus Sutras” from the seventh century and in a monument dating from the eighth, we have evidence of Chinese Christians assimilating Jesus into their own syncretic religious framework: “Jesus emerges as the embodiment of a mixture of Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism,” Sugirtharajah notes. In contrast, a 1602 work by Jesuit Jerome Xavier called Mirror of Holiness follows Portuguese colonization and the establishment of the Mughal empire in northern India, and, while emphasizing the connections between the gospels and the Qur’an, advances a very Catholic, Counter-Reformation version of Jesus.

Sugirtharajah’s detailed examination of subsequent Asian treatments of Jesus reveals a startling variety among them. Some converts to Christianity sought to define Jesus as a Jina or Guru (see Manilal Parekh [1885–1967] or Francis Kingsbury [1873–1981]). Others used a half-baked version of Jesus to construct their own messianic fantasies, as in the case of the Chinese Hong Xiuquan (1814–1864), leader of the Taiping Rebellion, who considered himself Jesus’ “divine younger brother.” In India, with its ancient Vedantic tradition, others resisted claims made for Jesus. The charge by certain European scholars that Christ was simply a myth was taken up by the Hindus Chandra Varma (Christ a Myth, 1903), and Dhirendranath Chowdhury (In Search of Jesus Christ, 1927). The Sri Lankan Ponnambalam Ramanathan (1851–1930) and the Indian Hindu Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (1885–1975) argued for the superiority of the Vedantic tradition by interpreting the worth of Jesus in terms of his “growth” toward that form of spirituality.

In Korea, the Christian New Testament scholar Ahn Byung-Mu (1922–1996)—an erstwhile disciple of German New Testament theologian Rudolf Bultmann—found in the historical Jesus the basis for Minjung theology, which emphasizes, in the fashion of liberation theology, the plight of the oppressed. And in Japan, the novelist Shūsaku Endō (1923–1996) displayed a career-long fascination with Jesus as a “maternal messiah” who was strong precisely through his weakness (see also A Life of Jesus, 1973).

Sugirtharajah has admirably filled a gap that most readers, including scholars specializing in the study of Jesus, are not even aware of. And if his own post-colonial proclivities sometimes seem intrusive, especially in his editorial comments on the respective authors, his treatment of the subject matter more than makes up for these minor transgressions.

Jesus in Asia

R. S. Sugirtharajah

Harvard University Press, $29.95, 320 pp.

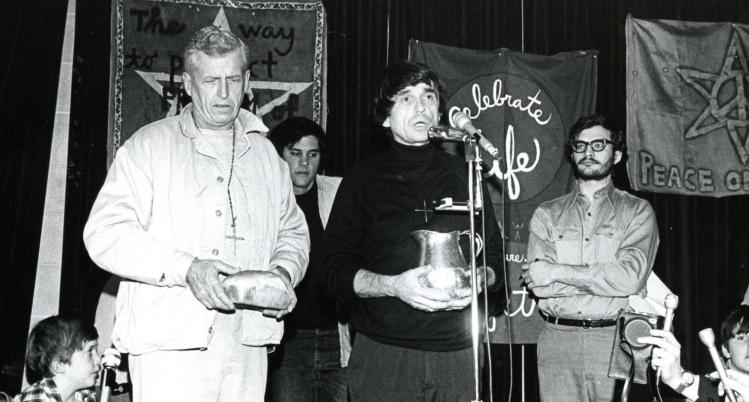

When Daniel Berrigan died in 2016 at the age of ninety-four, many of us recalled him mainly as the “radical priest” of the 1960s and ’70s, when he and his brother Philip gained notoriety for protesting war and nuclear arms and for burning draft cards as part of the Catonsville Nine. Berrigan was fortunate, however, to have had a much younger companion and colleague in Jim Forest, co-founder of the Catholic Peace Fellowship, who is able to provide a fuller portrait of a man who must surely be included among Christ’s true disciples and prophets of the twentieth century alongside his role models and mentors, Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton. Forest gifts readers with a positive but truly candid picture of the Jesuit with whom he protested for peace.

We are reminded of what we ought not to have forgotten (or what we ignored): that Berrigan was first of all a gifted and prolific writer. His first volume of verse in 1957 won the Lamont Poetry Award, and he would go on to publish fourteen more volumes of poetry before his death. But there were also more than forty other books, including the kind of commentary on contemporary issues that we associate with the later Thomas Merton, as well as nine biblical commentaries that emphasize, as we might expect, the prophetic dimensions of Scripture.

We learn that Berrigan traveled widely, and in his peripatetic career taught at twelve different seminaries, colleges, and universities. We learn of the importance of his loving yet at times tense relationship with his younger brother Philip, as well as of his mutually admiring friendship with Vietnamese monk and poet Thich Nhat Hanh. We learn how, when imprisoned at Danbury, he almost died from an allergic reaction to medication. We learn as well of the range of his social commitments, all of which he personally pursued: civil rights, peace in the Middle East and Ireland, the right to life in the face of abortion, and ministry for those with AIDS. And we learn that, to the very end, he combined a life in community with fellow Jesuits with a willingness to put his frail body on the line; he was last arrested at a protest at the age of ninety.

Forest’s combination biography-and-memoir—his own participation and correspondence with Berrigan is a major part of the story—includes many photographs, as well as copious and pertinent quotations from Berrigan. It succeeds wonderfully in telling the story of a complex man who, for all his fame, was and remains too little known.

At Play in the Lions’ Den

A Biography and Memoir of Daniel Berrigan

Jim Forest

Orbis Press, $30, 352 pp.