Paul Farmer’s death last week at the age of sixty-two comes with a sense of profound loss, but also joy. Words can’t adequately capture the impact he’s had on my life, on the way I see the world and my place in it.

His work in global health was transformative. He gave many of us working in the field a new vocabulary that overcomes “failures of imagination” by seeing what is possible if we work together in partnership. His life and work embraced proximity to the poor and pragmatic solidarity. “It isn’t just signing a petition or voicing one’s displeasure or anxiety,” he’d say, “but actually doing something with solidarity.” His catchphrases—“the failures of imagination are the biggest failures” and “persistence is the secret sauce”—are always dancing in my brain. His language of accompaniment—working and walking with others, not bestowing charity on them—drives how I teach. In my undergraduate international development class at the University of Notre Dame, I talked about Paul, the impact of his work, and the organization he helped found, Partners in Health (PIH) on February 22, the day after he died. I must admit, the class was a rambling, maudlin mess. I didn’t do Paul justice. But it is hard to do him justice.

When Farmer was a boy, he moved often, including to Florida, where his family of eight lived for five years in an old school bus that his father had converted into a mobile home. After graduating from Duke University in 1982, he traveled for the first time to Haiti, a powerful connection he maintained throughout his life. While traveling back and forth to Haiti, he earned both a PhD and an MD from Harvard University and co-founded PIH. His New York Times obituary described him as “a public health luminary.”

“I have fought the long defeat and brought other people on to fight the long defeat, and I’m not going to stop because we keep losing. Now I actually think sometimes we may win.” This is a well-known Farmer quote from Tracy Kidder’s best-selling book, Mountain Beyond Mountains: The Quest of Dr. Paul Farmer, A Man Who Would Cure the World. I actually remember him more celebrating, joyfully, all the “wins”—and in some unlikely places. I saw one of these wins when I went to Haiti in 2002 for the first time. Like many others, when I saw PIH’s Zanmi Lasante clinic complex in Cange, I was blown away by all that had been accomplished on the dusty, rocky central plateau in Haiti. The area around the clinic was so verdant, rich with trees and beautiful flowers that Paul had helped plant when he founded the clinic with friends and Haitian colleagues in the 1980s.

I remember our small group gathering in a conference room with crepe paper hanging from the walls. One of the patients, Charlene, who had been in the clinic for months, was being discharged, and was sitting in the middle of a circle of chairs. Paul and his colleagues had orchestrated many such farewell ceremonies for patients who had long recoveries. Charlene told a harrowing story of illness, tuberculosis and more. “It felt like I had a giant snake in my belly and chest, eating my inside.” She then told of the incredible kindness, care, and healing that she had received at Zanmi Lasante. She concluded, “I am sorry I do not have any gift to give to you—doctors, nurses, and all our guests—but my story is my gift, and I give it with all my heart.” We applauded and cried. That was classic Paul. Celebrate the victories.

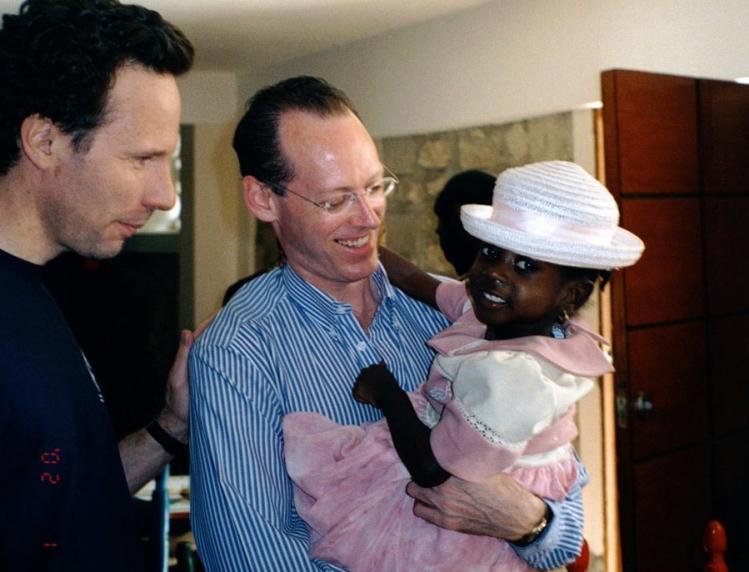

And there were victories to celebrate around the globe: ninety-pound men with TB who regained their strength and went on to live long and healthy lives in Haiti, mothers who didn’t die in childbirth in Sierra Leone, and babies who were premature and deathly ill who grew into healthy toddlers in Rwanda. Paul also celebrated big wins like treating patients who had multidrug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) in Peru when global health officials said it would never happen because it was far too expensive. Or when funding came from the George W. Bush administration for the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) program to treat people globally with HIV/AIDS, funds which ultimately saved tens of millions of lives. These sea changes in attitudes and funding came, at least in part, because PIH had demonstrated that people with MDR-TB and HIV/AIDS could be effectively treated in resource-poor settings around the globe.

Paul celebrated the opening of Haiti’s modern new hospital in Mirebalais in 2013, built after the nation’s teaching hospital was destroyed in the 2010 earthquake. One of the largest solar-operated hospitals in the world, it was called “University Hospital Mirebalais” from the start. When people said, “but there is no university,” Paul would answer, “not yet!” Today it is the largest teaching hospital in Haiti.

He celebrated the launch of the amazing University of Global Health Equity in 2019 in Butaro, Rwanda, with the country’s president and minister of health, and the newly inaugurated Cancer Center of Excellence in Butaro where Paul was treating patients the day before he died in his sleep. As author Tracy Kidder texted shortly after his death, “Just to remember, he lived a very full and rewarding life and had been treating patients shortly before he died, which means he died happy.”

Over the past couple of days, I have spent hours talking with Paul’s friends and colleagues, remembering him, how visionary and how human he was, and recalling the crazy ways he seemed to make connections everywhere. He had nicknames for everyone. It was one of a dozen ways he seduced people into joining the work, but it also expressed his real friendship and love. He called me “Green Light Reifenberg” in the 1990s, because when I worked as an administrator at Harvard, I helped PIH surmount some bureaucratic hurdles within the university. (Paul could never understand why bureaucracies, though generally supportive of his work, would sometimes get in the way of doing something good for someone else.) Then the nickname changed. For the last dozen years, he called me “Estebe,” a Spanglish version of my name, mostly because he enjoyed ribbing me about my gringo accent when I spoke Spanish. “Estebe,” he would say in front of a group of people, “say fosforos!,” hoping I would indulge him, bad accent and all, which would send him into peals of laughter. On February 16, I saw Paul on a Zoom call with forty other PIH board members. “Estebe!” he wrote in the chat. He always did that, and it always made my day. If you could see his keyboard on the Zoom screen, you’d see his long fingers flying as he sent dozens of chats to other board members, nicknames leading the way. He was like that everywhere he went, and he was always going somewhere.

He was generous, even as the demands on him grew. He taught at Harvard, wrote books, helped lead a global health organization, and ministered to patients across the globe. There was always a long queue of people asking him to write introductions for their own books. I had sent him the manuscript of my own book, Santiago’s Children: What I Learned about Life at an Orphanage in Chile, with the same request. In the middle of the night, I later learned, between seeing patients in Lesotho, he wrote a poignant introduction to my book. Paul was then kind enough to be on a panel about it at Harvard. When it was his turn to talk, he asked the moderator if he could invite my daughter, Natasha, to the stage. I’m not sure if the idea of your thirteen-year-old talking about you to a large audience strikes fear into all parents, but it certainly did me. Paul handed Natasha the microphone. She spoke, in a very poised way, concluding with “My dad will probably try to tell some dumb jokes, and they won’t be very funny, but I hope you laugh anyway…and yeah, please clap at the end.” Paul howled with laughter. Long after, he remembered that evening, not for what he or the other panelists said, but what Natasha said. When I told Natasha, now in law school, that I was struggling to write something about Paul, she texted me, “Emphasize his joy and sense of humor…. He saw such awful things all the time but was joyous and funny!”

Whenever Paul visited Notre Dame, he said the university had that “good Catholic social-justice vibe.” Paul’s Catholicism was part of his DNA, though like many things in his life, it was imbued with complexity. One thing is certain, though. He was greatly influenced by the Catholic tradition and his life was, in many ways, organized around the corporal works of mercy.

One of his biggest joys in coming to Notre Dame was seeing Fr. Gustavo Gutiérrez, a Peruvian priest, often called “the father of liberation theology,” who at the time spent half the year at Notre Dame and the other half in Peru. Paul had read Gutiérrez as a young man when he was first working in Haiti, and the theologian’s ideas—on structural violence, the preferential option for the poor, accompaniment, and more—stayed with Paul for his whole life and infused the work of PIH. As an adult, Paul developed a deep friendship with Fr. Gustavo, and kept a picture of the two of them on his desk. They knew each other’s work well, and decided to publish a book together, In the Company of the Poor: Conversations with Dr. Paul Farmer and Fr. Gustavo Gutiérrez.

I had the privilege to help launch the book, with Paul and Fr. Gustavo on the stage at Notre Dame. From the speakers’ podium, I read from a longish quote from Desmond Tutu extolling the virtues of the book, skipping parts a few parts along the way. “Rarely have two such distinctive and complementary voices,” I read, “been raised together with more heartwarming and instructive results than here In the Company of the Poor.... The book is erudite, fresh…and witty.”

Paul interrupted, loudly enough for the audience to hear: “I thought he said even at turns, witty.”

I looked over at him, surprised. “Did you write that, Dr. Farmer?” I asked.

“No, but it bothered me that there were turns where it wasn’t witty.”

He turned to Fr. Gustavo and wondered aloud if their common project wasn’t more than just “at turns” witty. Fr. Gustavo beamed.

Yes, Paul was witty. But that wasn’t the first of his qualities to stand out. He had a remarkable ability to connect with everyone, and especially students, probably because he was willing to tackle seemingly unsolvable problems and to approach then in such personal and human terms. He lived a life full of hope and action, and he made a lasting impact.

At the end of an evening’s talk in an overflowing auditorium at Notre Dame in 2016, he took questions from students, and then met with hundreds waiting in line after his talk. Many students brought him things to sign, including his own books or well-worn copies of Kidder’s Mountain Beyond Mountains. One student brought her Notre Dame yearbook, another her statistics textbook. Farmers signed them all. “Don’t spend more than 12.4 percent of your time arguing with people,” he told a student who asked how to make a difference. “Spend the rest of your time doing stuff.” “You’re not the Dominic who wrote me an email are you?” he asked another student. I know this because Dominic, now in medical school, just wrote to me. “I didn’t know Dr. Farmer well at all, but I did have a few email exchanges [with him] while I was at Notre Dame and chatted with him after one of the discussions he led…. I was struck then by him remembering me despite us only having a brief email interaction…. I remember Dr. Farmer as being one of the first people I’d met who I thought ‘my life would be well lived if I live like he’s lived.’”

So many people I know were changed by him and reimagined their own lives after meeting him—or just reading about his life and work. They changed majors, committed their lives to working with the most vulnerable, thought differently about what was and wasn’t possible. He accompanied so many, so well, and connected them with a vision of something larger and better, “the refashioning of our world.” And he did it with imagination, intelligence, and joy. My heart aches for this loss.