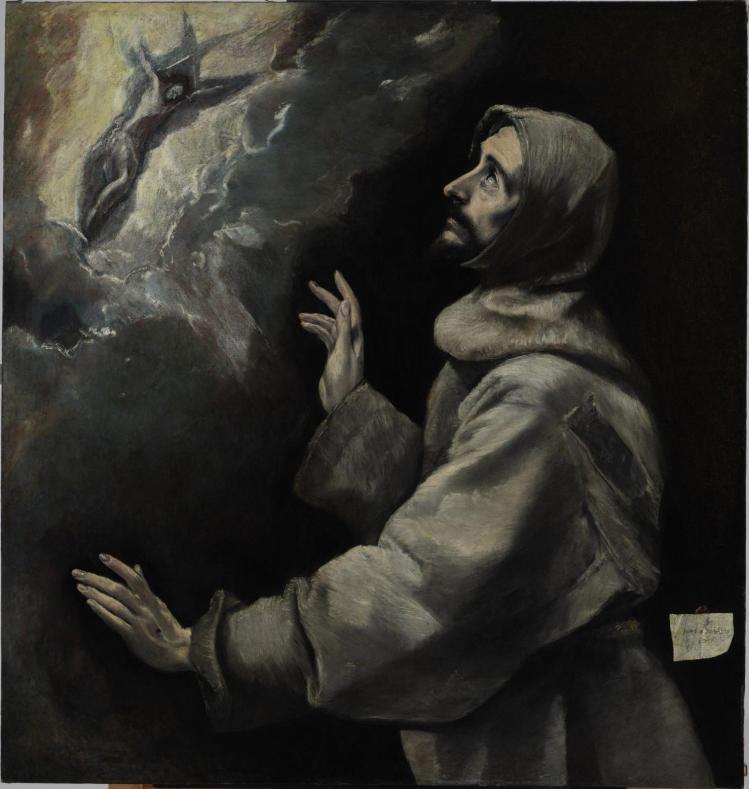

Among the villains who populate the lives of the saints, none stands out quite like Peter Bernadone. Peter is famous for abusing his son, St. Francis of Assisi, one of the most beloved figures in the history of the Western world.

Students of Church history typically give Peter no sympathy. And why should they? Judging from the earliest biographies of Francis, written soon after his death in 1226, Francis disowned his father and had nothing further to do with him for the rest of his life. It seems that Francis, who took literally the words of Mark 10:21 to “sell what you have and give to the poor,” also observed the words of Luke 14:26: “If anyone comes to me and does not hate his father and mother and wife and children and brothers and sisters, yes, and even his own life, he cannot be my disciple.”

This passage has concerned me since my parochial-school days. It was contrary to the fourth commandment to honor thy father and mother. And, moreover, I had no plans to hate my parents. Could I then be a good follower of Jesus? As an adult, when I puzzled over Francis’s extreme behavior, I figured that Francis was taking these words from Luke literally. But perhaps we need to look deeper at this fraught father-son relationship and this gospel verse. Might there be reason to have some sympathy for Peter Bernadone? More importantly, could Francis have shown more loving compassion toward him than he has been given credit for?

First of all, who is Peter Bernadone? In his book Naked Before the Father: The Renunciation of Francis of Assisi, the late historian Richard C. Trexler presents evidence that the basis of Peter’s fortune was the considerable money that his wife Pica brought to him from a prior marriage and possibly from her own wealth. Peter indulged Francis’s every whim, according to the earliest biographies of the saint. He financed the adolescent Francis’s plans to become a soldier and knight, a status that was possible for commoners with sufficient money to buy swords, armor, and horses. In 1202, when Francis was twenty, he fought in a losing battle against Assisi’s enemy Perugia and was taken prisoner. Peter ransomed him and was tolerant of Francis’s slow emotional and physical recovery—until Francis did an about-face and decided to serve God and the poor.

Thomas of Celano, Francis’s first biographer, wrote that when Peter heard Francis had become an object of ridicule for his new life of penance, he “immediately arose, not to free him, but rather to destroy him. With no restraint, he pounced on Francis like a wolf on a lamb and, glaring at him fiercely and savagely, he grabbed him and shamelessly dragged his home.” Once inside, Peter taunted, beat, and tied up his son. Pica stepped in to protect Francis, but Peter began to abuse his wife as well.

Finally, Peter accused his son of stealing valuable red cloth from him and took legal action. Why? Trexler suggests that Francis would have been an heir to a large share of Pica’s wealth. If so, Peter may have been eager to terminate Francis’s legal standing as a family member before Pica could bestow any of her capital on her unpredictable son, who might use it for the Church or even for prayers for her soul. Peter’s determination to protect Pica’s (and his own) fortune from anything that Francis might do could explain why he turned against the son he loved so much.

Peter vanishes from his son’s story after Francis stripped himself naked and disowned his father and his wealth at a public trial on the bishop’s plaza. This leaves us to believe that Francis, who preached love and forgiveness, turned his back on his parents and never dealt with them again, even in the years when he lived within walking distance of their home. Was Francis guided by the words of Luke?

Luke was not actually telling us to hate or abandon our loved ones, as David Lincicum, associate professor of theology at the University of Notre Dame, explained to me. According to Lincicum, this harsh-sounding phrasing comes from a disjunctive way of speaking in Semitic languages like Hebrew or Aramaic that offers a stark, perhaps unsettling choice: to prioritize following Jesus above all other relationships, including familial ties.

Did Francis, who advised his followers that “if you do not forgive people their sins, the Lord will not forgive you yours,” really shun the man who raised him? I do not think he did. A little-known comment that Francis made to the bishop of Imola convinces me that he reconciled with Peter Bernadone. Francis went to the bishop repeatedly to ask for permission to preach in his diocese, and was rejected each time. Finally, the bishop asked why he kept coming back when his answer never changed. Francis replied, “If a father drives his son out of one door, he must come back in another.” Could Francis have made such a statement if he had not done the same thing himself?

Peter, who had probably died by 1215, may have lived to see Francis begin to achieve the respect that would bring centuries of glory to the Bernadone name. He may have been proud to see the way people came to regard his son. At least we can hope so, for both their sakes.