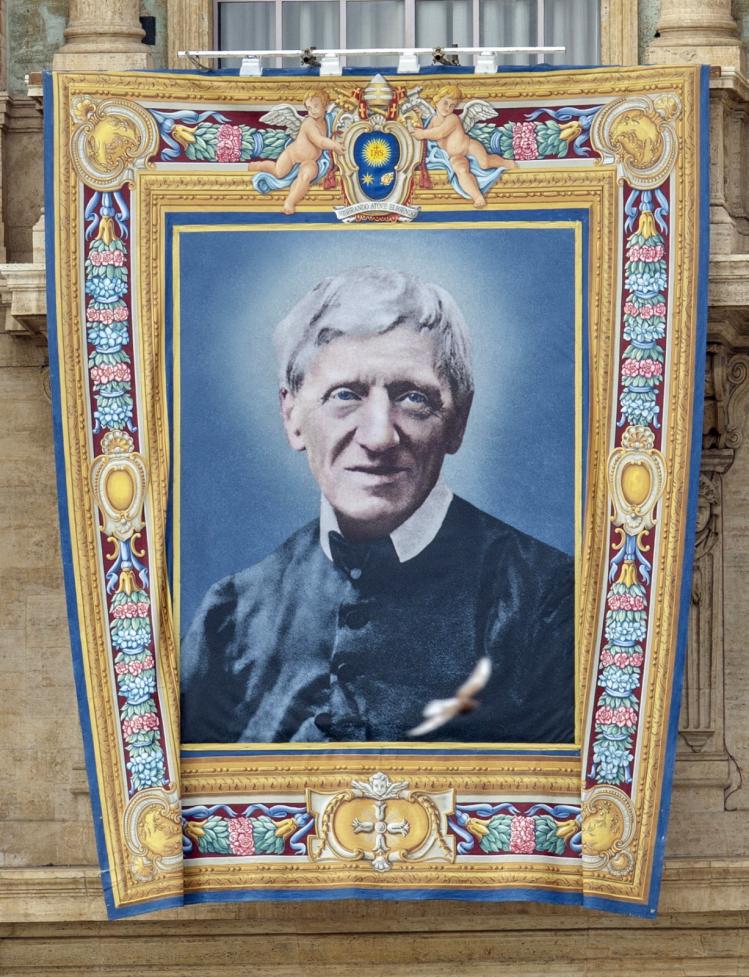

To meet Ignatius Harrison, the Oratorian tasked with promoting the canonization cause of John Henry Newman, is to catch a little glimpse of the saint himself. Fr. Harrison lives with other Oratorians in the house Newman designed and built in Birmingham, England, and follows his prayer life as closely as possible. He is portly and jowly where Newman was beak-nosed and spindly, yet Fr. Harrison’s black cassock with its crumpled white collar is identical, as are his shyness and exquisite Englishness, and that soft Victorian way of speaking that belongs to the age before television.

At the Vatican press office the astonished indignation of our waiting scrum of reporters and camera crews on being told Harrison won’t give TV interviews was priceless. When the Tablet’s Christopher Lamb and I sat down with Harrison, he was still shaking his head at all the “fuss,” worrying that our taking of his photo was “vanity.”

But then he began speaking in perfectly modulated, TV-friendly soundbites. Harrison is not only soaked in Newman’s thinking but also has the saint’s forthrightness and clarity and bold openness to new things. Newman, he tells us, would have been delighted by the way the church has developed since his time. “His main ideas, that seemed to some in Rome at the time dangerously liberal, have now become embedded in the mind of the church and seem to most of us quite normal and normative,” he points out, citing as examples his insistence on the divine origin of human conscience, his insistence on the protagonism of the laity, and above all his “carefully elaborated” understanding of the true development of Christian doctrine, the way doctrine becomes more true to itself as it grows in response to new times and challenges.

Asked about Pope Francis and the synod on Amazonia, Harrison refuses the role of curmudgeon. “It seems to me—not that I have any prophetic insight—this is going to be even more important in the future than it was to Newman when he was writing, because the church is exploring, as we know, the peripheries, looking at possibilities and opportunities that we really hadn’t considered before,” he says.

He would certainly not be in the opposition camp. “I think John Henry Newman would say, fine, now let’s look at that in the light of the church’s tradition, and in the light of our belief that the Holy Spirit guides the church in every age and at every moment.”

Newman’s mind was so refined and supple that he can sometimes seem like a helicopter that never lands. Thus, his zinger quote in his Letter to the Duke of Norfolk—“I shall drink to the Pope, if you please, still, to Conscience first, and to the Pope afterwards”—has long been brandished to justify Catholic dissent, whether by liberals annoyed at John Paul II twenty years ago or nowadays by rad-trad opponents of Pope Francis’s magisterium. But Newman saw conscience as an “aboriginal Vicar of Christ,” one that leads eventually to submission to a dogmatic and institutional Christianity.

So while conscience is the “first principle,” it “does not repose on itself,” as he puts it in Grammar of Assent, but “dimly discerns a sanction higher than self for its decisions.” It searches restlessly, one might say, until it comes to rest in submission to the papal magisterium, “like coming into port after a rough sea,” as he famously described his conversion in the Apologia.

The great Jesuit Erich Przywara said that for Newman the “principle of conscience” and “the principle of dogma” turned out to be “one living principle: the dawning and consummate manifestation of the One God—from the beginnings of His appearance in conscience, through to the fullness of His appearance in an authoritatively infallible Church.” And yet—you can’t talk about Newman without these qualifiers—he was no ultramontane, and was wary of papal autocracy. His opposition to the declaration of infallibility came from his accurate prediction that weaponizing the papacy in the nineteenth-century equivalent of the culture wars would end up feeding the false polarization of faith and freedom.

He was prophetic, too, in deploring long pontificates. “It is not good for a Pope to live twenty years,” he said of Pius IX. “It is an anomaly and bears no good fruit; he becomes a God, and has no one to contradict him, does not know facts, and does cruel things without meaning it.” (During the twenty-six-year papacy of John Paul II, Benedict XVI reached the same conclusion.)

It is almost a cliché to say Newman resists easy categorization. “It would be very imprudent to label him either a traditionalist or a progressive, a liberal or a conservative, because his whole life was a humble pursuit of truth led by the kindly light of the Holy Spirit at every step,” says Father Harrison. That makes Newman, as others have often said, the patron saint of the postmodern searcher, who has to pick up every rock to see what is underneath it before she will rest on it. But Newman is very unpostmodern in believing that along the road there will be the Rock, and that meeting it is not a matter of coldly weighing up arguments and options.

Indeed, the distrustful self-witholding of the postmodern self is the very opposite of Newman’s turbulent love affair with truth. His journey, recounted in his Apologia, is essentially a story of passionate conversions, each one revealing more of the Rock, as he boldly sets out to live faithfully in the tension of opposites.

So while Newman was no liberal in the common sense of the word, his was a deeply liberal frame of mind. His Idea of a University—the best book in the English language on the nature and purpose of university education—draws from the assumption that, as Archbishop Diarmuid Martin of Dublin put it in a lecture at the Irish College in Rome on Friday, “faith is more than intellectual assent…. It always contains an element of continuous searching and seeking, and therefore an element of risk.”

That is why, as Harrison told us in his interview, Newman “would have been a Remainer” in the Brexit debate. “He would say: ‘Why would England want to cut itself off, spiritually speaking, from Christian Europe, from Christian, Western civilisation?’” Harrison adds: “I think he would opt for anything that would contribute to a closer spiritual unity between different countries and different nationalities.”

When I put that quote to Archbishop Martin after his lecture on Newman’s ultimately failed attempt at creating a Catholic university in Dublin, the audience burst into laughter at the idea that England’s first saint in three hundred years had a view on Brexit. But the archbishop agreed with Fr. Harrison. “The idea of a university as a place of universal learning can only come from a person who has a broad understanding of relationships and culture and of our common history,” the archbishop said.

Prince Charles, who is representing the Queen at the canonization, says much the same thing. Newman, he has written in the Tablet, could “advocate without accusation, could disagree without disrespect and, perhaps most of all, could see differences as places of encounter rather than exclusion.” That makes him especially relevant at a time of “grievous assaults by the forces of intolerance on communities and individuals, including many Catholics, because of their beliefs,” the prince adds.

Could this now be Saint John Henry Newman’s role in the church and the world—as one who teaches us how to seek with rigor and honesty in a post-truth era?

Like Pope Francis, Newman was relaxed about theological conflict and disagreement, says Fr. Harrison. “He says this is our lot, this is how it has always been, but what matters above all is seeking God.” He is happy that Newman is declared a saint now, for it means “he no longer belongs to us exclusively. He’s the saint for the universal church and for people of goodwill.”

As Matthew D’Ancona explains “post-truth” in a recent book of that title, it is essentially an emotional phonomenon. “It concerns our own attitude to truth, rather than truth itself.” The epistemology of post-truth urges us to choose sides rather than weigh evidence. In a post-truth world, we construct narratives that feed our grievances or offer to protect us from what we fear, and the facts are arranged to suit the narrative. It is no longer enough to drive out lies with well-chosen facts, for there is no longer a distinction between opinion and facts. Nor can there be any hope to dislodge the emotional apprehension of truth by reverting to the cold science of reason. The means of correcting post-truth have to match the prevailing culture.

Who better to restore our relationship with truth than Saint John Henry Newman? He understood that truth lies outside and beyond us, yet beckons to us through our consciences, and that the end of all our strivings is not an idea but a person, who is reached not firstly through reason but “through the imagination, by means of direct impressions, by the testimony of facts and events, by history, by description,” as he wrote in Grammar of Assent. Newman shows us that by embracing what often appears to the mind as contradictions and opposites and trusting in the kindly light to lead us, we will eventually come into port. That’s what makes him, in a post-truth time, the saint our age badly needs.