Before the rise of professional historiography as we know it today, European scholars tended to start their accounts of the human story way, way back—as in, the Garden of Eden. In what was often called “universal history,” humanity’s story was depicted as progressing through certain predetermined, discernable “stages” or “ages,” culminating in the Last Things. Such an approach persisted, in a more secularist register, into the Enlightenment: in the philosophe Condorcet’s ten-stage account of the “inevitable perfection of the human race”; in Hegel’s lumbering pontifications on Weltgeschichte (world history); or later in August Comte’s vision of humankind’s passage through three ages, from the theological through the metaphysical and, finally, to the mature “scientific” or “positivist” stage, which Comte confidently felt he was advancing in his own writings.

This effort to detach history from theological and philosophical concerns and remake it as a just-the-facts, scientific enterprise strongly shaped the discipline that emerged in the nineteenth-century academy. As physicists sought predictable laws in the natural world, so historians sought them in the human world. George Bancroft, a nineteenth-century U.S. historian, for example, traced the roots of American liberty to Teutonic forests and Luther’s Reformation, addressing these words to the American Historical Association in 1886:

The movements of humanity are governed by law.... The growth and decay of empire, the morning lustre of a dynasty and its fall from the sky before noonday; the first turning of a sod for the foundation of a city to the footsteps of a traveler searching for its place which time has hidden, all proceed as it is ordered. The character of science attaches to our pursuits.

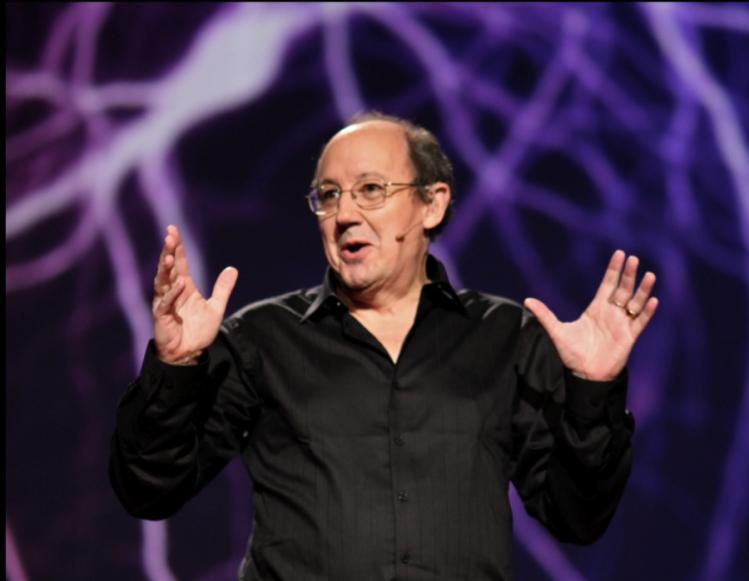

This context will help us assess so-called Big History, an approach to teaching pioneered and promoted by David Christian, professor at Macquarie University in Australia. Christian’s captivating instruction, showcased in a celebrated 2011 TED talk titled “The History of our World in 18 Minutes,” has become hugely popular online—and has gotten a big boost from Bill Gates. After stumbling across it during a late-night workout, Gates arranged to meet the professor and soon decided to invest millions in an effort to get Christian’s brainchild into American high schools.

Big History has some obvious charms. It aligns with the Common Core standards adopted in most states, and provides a wealth of well-organized material online—for free. It uses project-based learning in a comprehensive ninth-tenth grade sequence, and can also function as a “capstone” class or be incorporated into existing curricula. And it is exciting. Where high-school history teachers sometimes struggle to make topics relevant—recently, our daughter’s U.S. history class tried to use new NFL concussion rules as a way to get students interested in the Progressive Era—Big History ignites student interest with a drama of universal sweep and high stakes for our future. (The online curriculum proclaims that “decisions made by the generations of humans that are alive today” can either free the future from “conflict, disease, and degradation”—or undermine “the foundations of today’s world.”) And Big History, whose advocates fault conventional secondary-school curricula for randomness, promises students a way to draw connections among disparate disciplines. As project advisor Bob Bain puts it, “Most kids experience school as one damn course after another; there’s nothing to build connections between the courses that they take.”

In the largest sense, Big History goes the older “universal history” one better: it is not merely an effort to see how one country fits into the world or how one age follows another, but how our world fits into the deep time of the entire universe. Forget 1492 and 1776, forget decades and centuries; we’re talking about eons. David Christian’s narrative moves across eight “thresholds,” from the Big Bang to the rise of agriculture, cities, states, industry, and technology; homo sapiens don’t show up until threshold six. Christian drew his method from the Annales school, an early twentieth-century French school of history that prioritized quantifying the longe durée: broad, impersonal movements in geography, demographics, consumption, and the like.

But where Annales history was written in a dryly academic style, Big History is sexy. And it is catching on. As Andrew Ross Sorkin reported in a 2014 cover story for the New York Times Magazine, the California school system is paving the way for the state’s thirteen hundred high schools to offer it, and the project’s website lists several hundred schools in the United States, Canada, and Australia that already have embraced it. Sorkin reported widespread wariness toward the idea of a history program paid for by Bill Gates, quoting New York University’s Diane Ravitch, a prominent critic of corporate school reform. “I wonder how Bill Gates would treat the robber barons,” Ravitch mused aloud. “Bill Gates’s history would be very different from somebody else’s who wasn’t worth $50–60 billion.”

WE ARE WARY TOO, but not primarily because we fear Bill Gates is peddling rich-man history. The deeper problem, in our view, is that Big History is too big—too big, in fact, to be really history at all.

Historical inquiry can distort by over-specialization, looking at one place, person, or event too narrowly, without supplying the wider context. But going too wide also distorts understanding. Attempting to cover a vast stretch of space and time obscures understanding of contingent human actions. In raw scientistic fashion, Big History evicts subjective human experience from the curriculum, disabling the kind of teaching that (to quote Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn) seeks to convey “the whole weight of an unfamiliar, lifelong experience with all its burdens, its colors, its sap of life”—the kind of teaching that “recreates in the flesh an unknown experience and allows us to possess it as our own.”

Furthermore, as social historians recognize, a key element of any big story is the range of small stories it contains. Particular things happen for particular reasons to particular people, requiring close scrutiny of circumstances, personalities, beliefs, social conditions, ideas, motivations, inventions, elections, and so on. This recognition is not only a feature of methodology but a key humanistic reason for studying history in the first place—and a prophylactic against the solipsism of mistaking your own milieu as the apex of human reason. Not only is this goal not present in Big History; indeed, the project appears designed to delete it. History teachers properly want students to consider particular persons and events, to kindle capacities for moral reasoning, and to engage times and places utterly foreign to their own. But insofar as Big History has a storyline, it’s the glacial, improbable ascent of homo faber, Silicon Valley style: from the Big Bang to Bill Gates.

Big History also exhibits a dubious faith in what David Christian calls the “underlying unity of modern knowledge.” No fretting over a war between science and religion, or between the feuding “two cultures” of science and the humanities à la C. P. Snow, because historical knowledge exists within the house built by science. In the terms of the great German theorist Wilhelm Dilthey, Big History is all about Erklären, knowledge that admits sharp precision, not Verstehen, a more ruminative, reflective mode that encompasses nuanced empathetic understanding of people in remote times and places.

History teachers who are flattered to think that “history” can serve as the framework for organizing all knowledge would do better to worry that a Trojan horse is now inside their walls. Consider Christian’s claim to deliver all 13.7 billion years in 18 minutes (or in a few online lessons). What takes us through most of those billions of years are astronomy, physics, geology, chemistry, and biology. These are vitally important fields, but they are not methodologically recognizable as history—and certainly not history as a humanistic, empathy-inducing enterprise designed to plumb the cracks and crevices, the fathomless contingencies, of human experience.

Science and history can and should intersect, of course. Environmental historians long have studied the reciprocal relationships of nature and human activity, and the history of science deserves a much more prominent place in high-school and college curricula than it commonly receives. One might further argue that the job of a holistic liberal-arts education is to provide appropriate links between various disciplines.

But in presenting as history a visually beguiling panorama that is mostly science, Big History minimizes the significance of human experience, reducing it to a “stage” or “threshold” in the unspeakable vastness of time, energy, and matter. So it is both poignant and comical that the online version of the course recommends the following questions for instructor use: “What does 13.7 billion years of history tell you about yourself? How does knowing so much about the past change the way you think about the future?”

Answers may vary.