Thomas Merton died yesterday in 1968. We mark this on our calendars. Merton is so widely read that he might be keeping a good portion of the Catholic publishing world in business. It feels as if there’s a new book out on or of Merton every week. To be honest I marked Merton’s death on my calendar more for occupational reasons—to remind myself to pull something from our archives and post about it on Facebook. Commemoration days are good for social media, plus Commonweal has published a lot of Merton’s writing since he first appeared in our pages in 1946.

But what I found hit me unexpectedly hard in much the same way as Boston-based pastor Rev. Osagyefo Uhuru Sekou did last night at the NYC Catholic Worker auditorium when he exhorted white people in the audience to get out and “risk their lives to stop black kids from getting killed.”

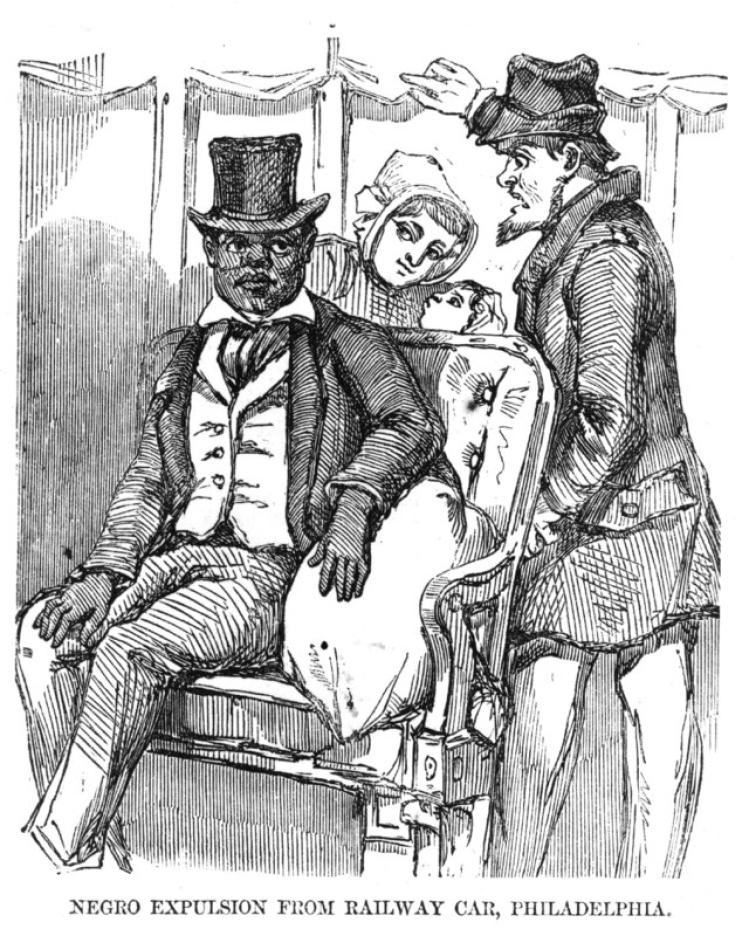

Merton’s last submission to Commonweal was received a couple months before his death and published posthumously. It’s an anti-poem called “Plessy vs. Ferguson: Theme & variations.” In 21 sections it dissects one quote from 1896 taken from the summary of the Supreme Court’s 7-to-1 opinion that it was constitutional for the state of Louisiana to require the East Louisiana railroad to have separate train cars for whites and for blacks, as long as they were “equal.” And so it was constitutional to arrest Homer Plessy for refusing to vacate the white car, because he was known to be one-eighth black. The poem begins with the quote:

We consider the underlying fallacy of the plaintiff’s argument to consist in the assumption that enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so it is not by reason of anything found in the act but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it. (Plessy vs. Ferguson 163. U.S., 537.)

Plessy’s lawyers had argued that the state violated Plessy’s 14th Amendment rights to be equally treated a citizen, and the 13th amendment prohibiting slavery, because the act of separation was decided and enforced exclusively by whites, thus making the black man “property.” The state prevailed, and through this new “separate but equal” doctrine opened the way for states to lawfully segregate public places until Brown vs. Board of Education in 1954.

Though I was familiar with the decision I had not known about the specific details of the case. I always knew segregation was wrong, I never knew this was precisely how it came to be. And I never wondered.

Rev. Sekou, whom I mentioned above, arrived in New York City fresh from demonstrating in the streets of Ferguson, Missouri, to compare notes with David Hartsough, a veteran of the civil rights movement 40 years ago, on “the struggle for justice in the United States of American, then and now” at the Catholic Worker auditorium. “We need your bodies. Shut up, and show up,” he demanded of the audience, in encouraging them to join the Millions March Day of Anger in New York City this Saturday.

Merton’s poem, the anti-poem from 1967, concludes “years later”:

We opened the door for the colored race. We knew it was their only way out. They themselves closed it. Perhaps they had misunderstood our motives. Thus we found ourselves all locked up together in the same construction. Only one question now remains: who will be the first to set fire to the building?