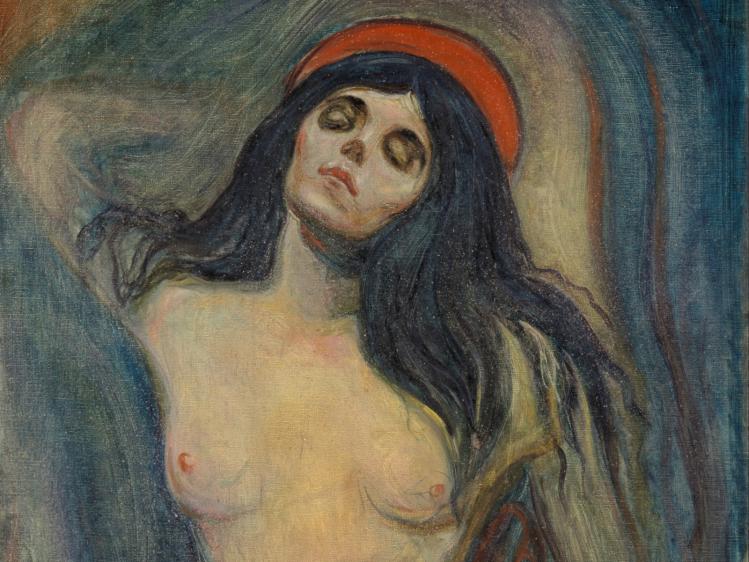

The painting’s called Madonna, but there’s no reason you’d think so. A naked woman twisting against a dark sky, in Edvard Munch’s typical hallucinatory colors, looking somehow both corpse-like and more alive than alive—none of this brings Mary immediately to mind. It’s sensual, but hard to imagine anyone finding it much of a turn on. The visuals are disturbing, almost violent, but at the same time comforting. Without the red nimbus behind the woman’s head, nothing about it would appear especially religious.

For a while, the Madonna was the only piece of art I owned; it hangs (well, it’s propped up) in my bedroom. It has never seemed disrespectful to me, but I will also admit that it’s the disturbing nature of the painting that draws me to it. And it’s that quality that seems to elicit two different, if equally mistaken, Christian responses to Munch’s painting. One is to see in Mary’s nakedness only the salacious preoccupations of a not-very-pious artist. The other is to make the painting less disturbing, draining it of its peculiar force, as Michael Neubeck did in an article for America last year. Munch depicts Mary, he writes, as “an adult and a partner, one who has made and continues to make choices.”

But there’s no need, least of all on religious grounds, to flatten the work’s meaning in these ways. The violent nature of the painting, and of the dark story of the real-life woman most commonly associated with it, actually tell us something important, or at least useful, about Mary.

Much like the ambiguity surrounding the painting—Madonna or no?—the identity of Munch’s model is also a mystery. One popular theory identifies her as Dagny Juel Przybyszewska, a close friend of Munch’s who was considered by many in their shared circle to be a femme fatale. Her peers described her in extreme terms, calling her “goddess, queen, sovereign” but also “cold” and “deadly.”

According to Dagny’s biographer, Mary Kay Norseng, however, Munch himself denied that Dagny was the model in a letter, owning up only to “a certain likeness” between the two. But since this letter from Munch doesn’t exist in his hand, we can’t know for sure that he wrote it. So it’s a Madonna that’s not a Madonna, with a model who might not even be the model, and a painting that Munch painted, as he was wont to do, several different times. (One variation, with sperm and a fetus, is both more obviously Madonna-like and more sexual.)

Whether the painting truly was of her or not, Dagny was fond of it, even writing to Munch to ask for a lithograph of it and Scream. That she, the “snake” of her social circle, could be supposed to be the model for Mary might have seemed like a complicated joke.

But it’s a joke with an ugly ending: A mere five years after Madonna was painted, Dagny herself was shot dead in front of her young son. She had married a novelist who had been serially unfaithful to her and then attacked her and their marriage in his novels. She left him to travel with another man, who resolved—probably unbeknownst to her—to kill her. He defended his murder as benevolent, writing to Dagny’s estranged husband “I’m killing her for her own sake.” To her son, he wrote that she was “an incarnation of the absolute…she was God.… She believed that she had come to the world only so that you might be born.”

Here, too, Dagny becomes almost a parody of Mary: represented by her peers as sexually impure and predatory; murdered so that the pure mother within her could live. She existed so that she could be a mother, and only in her motherhood could her redemption—or any woman’s redemption—exist. Writing about the Madonna painting, her husband himself commented that

…there are moments when the woman ceases to be the vampire. In giving herself absolutely to a man the dirt is washed off and her lust to destroy and her shame disappear without a trace, her face shines in conception’s terrible beauty.

There is a moment in the woman’s soul when she forgets herself and everything around her and transforms herself into a formless, timeless and dimensionless creature, a moment when she conceives in virginity: “Madonna.”

Much like Bernini’s Ecstasy of St. Theresa, another work of art that steps right up to the line of what is and is not appropriate, Munch captured Mary, or an idea of Mary, in a moment of experiencing the sublime. But while Dagny’s husband and peers—and, for all we know, Munch himself—could conceive of this sublimity only in terms of sexual submission, wherein women are redeemed only by renouncing themselves for men, Munch painted another story. There’s no man in Madonna; Mary’s not looking at the spectator. Her face is turned to God.

One irony of the “Madonna/Whore” dichotomy is that Mary herself entirely transcends it, even if many of those who admire and disdain her do not. Her “yes” to God means making herself vulnerable to suspicion of sexual sin—as indeed Joseph, who knows Mary better than anybody, immediately assumes to be the case. And so while Mary is, on the one hand, a figure of imposing purity, she’s also someone who appears impure. She is as open to slander as any woman. She opens herself to God, regardless of consequences.

Mary has inspired some of the greatest works of Christian art—from Bach’s Magnificat to Henry Ossawa Tanner’s Annunciation. But if I were to quibble with them, it’s that they convey Mary’s holiness by depicting her as serene, sometimes even in her grief. But holiness can assume many forms; it’s the intensity of John the Baptist, too. Mary proclaimed that the mighty would be torn down and the rich sent away; is serenity really all we can find in her?

Munch’s Mary is strange and unfamiliar, but she’s a Mary for all of us—the mother of God, whose rescue will not come from giving herself to a man, from formlessness, or from self-obliteration. She is there for virgins, as she is for whores. She will give birth to her savior, but that savior is not peculiarly hers: it’s not Mary who is saved through Christ so much as all of us. Before God, she is naked, as we all are; she is pure, but in the way fire is pure. Her communion with God is wild and strange, not respectable, even a little off-putting. But that her soul “doth magnify the Lord”…well, that’s undeniable.