Interested in discussing this article in your classroom, parish, reading group, or Commonweal Local Community? Click here for a free discussion guide.

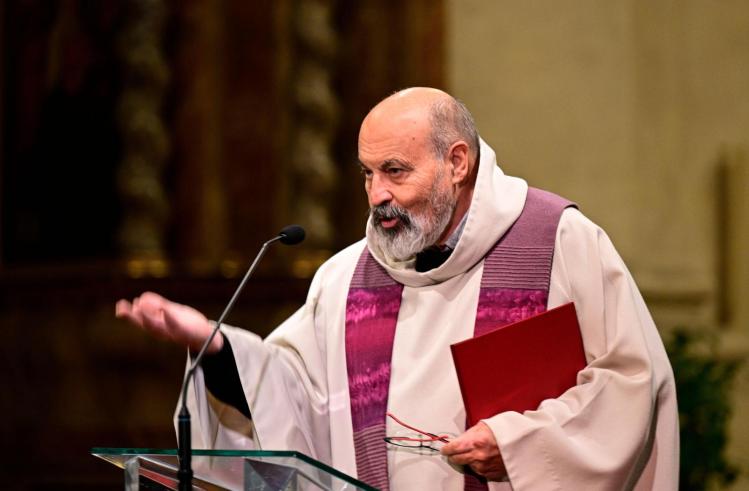

Msgr. Tomáš Halík is a Czech priest and professor of sociology at Charles University. Born in Prague in 1948, Halík earned his doctorate in philosophy in 1972. He was later ordained as a priest in the underground Church. Until the fall of Communism in 1989, he was banned from university teaching and worked in secret as an advisor to Cardinal František Tomášek, an opponent of the Communist regime. He also worked as a practicing psychotherapist during that time. His books include a memoir, From the Underground Church to Freedom, and several works of theology and philosophy, including Night of the Confessor and Patience with God. His most recent book, The Afternoon of Christianity, argues for a more mature and open Church. This interview was conducted over email with Zechariah Mickel, an editor at Wipf and Stock Publishers. It has been edited for clarity and length.

Zechariah Mickel: First, could you tell me about your education? What did you study, and where?

Tomáš Halík: I studied sociology, philosophy, and social psychology at Charles University in Prague from 1966 to ’72. Those were the years of certain political liberalization around the Prague Spring of 1968, when professors who had been banned for political reasons returned briefly, among them my teacher Jan Patočka, an important representative of European phenomenology and a disciple of Edmund Husserl. The Soviet occupation in August 1968 found me in Great Britain, where I took a semester of philosophy of religion at the University of North Wales. When I had to decide between returning to Czechoslovakia and emigrating, I chose to return and complete my studies. I obtained a PhD in philosophy from Charles University.

However, political circumstances changed at that time. When, in a speech at a university ceremony, I publicly thanked our teachers who had been expelled from the university again after the occupation, I was banned from academic work, as well as from publishing and traveling to the West.

From 1972 to ’78 I studied theology in underground courses and in 1978 I was secretly ordained a priest in the private chapel of a bishop in East Germany. I was not allowed to work publicly as a priest, so I worked in various civil occupations, for the longest time as a psychotherapist for alcoholics and drug addicts. At that time, I was licensed as a clinical psychologist. After the fall of Communism, I completed postgraduate studies in theology and religious studies at the Pontifical Lateran University in Rome and at the Pontifical Faculty of Theology in Wrocław (Poland). In 1992, I habilitated for theology and for sociology and began working at Charles University.

ZM: What about your conversion to Christianity—what were the circumstances surrounding that decision? Who or what led you to faith and to the Church?

TH: When I was growing up, Christianity became attractive to me for a number of reasons—mainly aesthetic and intellectual reasons (I admired Christian architecture, sacred music, and Catholic literature, especially books by G. K. Chesterton and Graham Greene). Certainly, political protest against atheism as a “state religion” imposed by the Communist regime played a role. I sympathized with Christianity but had still no contact with the living Church. It was still necessary for Christianity to get a “human face” for me.

This happened especially at the time of the Prague Spring, when I got to know a number of Catholic priests, professors of theology who had recently been released after fifteen years from the Communist prisons. They were truly heroic witnesses to the faith, and they became my fathers in the faith and inspired my decision to become a priest.

ZM: What was your process for discerning the priesthood? What was it like considering your options for ordination given the oppressive sociopolitical conditions?

TH: The spring of 1968 was the spring of my life and my faith. I was twenty years old. It was also the spring of the Church after the Second Vatican Council, and the Prague Spring promised the end of the repressive Stalinist regime. But the political hopes of the Prague Spring were ended by the Soviet occupation in August 1968, followed by another twenty years of Communist rule.

In January 1969, Jan Palach, a student at our faculty, burned himself to death to encourage resistance to the growing political repression that followed the Soviet occupation. I organized a requiem for Palach and carried his death mask to the church. His sacrifice was an impulse for me to get involved in dissenting circles. Dissent took different forms—political dissent of people like Václav Havel, cultural dissent (like organizing an underground university and publishing samizdat books and magazines), and religious dissent (the underground Church). I was in contact with political dissenters (Václav Havel was a close friend of mine for forty years) and especially helped connect cultural dissent and the underground Church.

Anyone who wanted to work publicly as a priest under Communism had to go through a state-controlled seminary and get a “state license” from the Communist authorities who controlled religious life. That license could be revoked at any time if the priest was “politically unreliable” or too active in priestly work. “Illegal” priestly activity without a state license (such as celebrating Mass in small groups at home) carried the risk of years in prison. The underground Church included priests who had their licenses revoked by the state and then had to work as night watchmen, window and toilet cleaners, heating technicians, and similar jobs. They were known to be priests and were constantly monitored by the police. The second group of “underground priests” were those like me who had studied theology in underground courses and been secretly ordained, either by bishops in the surrounding Communist countries (especially East Germany and Poland) or by secretly ordained bishops in Czechoslovakia. They had various civil jobs, and their priestly activities had to be kept strictly secret.

ZM: As you mentioned, during your years as a clandestine priest, you also worked as a psychotherapist. How did that arrangement work, and what were you doing as an underground priest during those years?

TH: I was ordained in the private chapel of the bishop of Erfurt in East Germany in the presence of four people. It was the evening before the inauguration of Pope John Paul II in October 1978. Even my mother was not allowed to know that I was a priest. For most of my years in the “underground,” I worked as an unofficial advisor and collaborator of Cardinal Tomášek, who gradually went from being a very cautious bishop to a symbol of resistance against the Communist regime. I prepared his sermons, pastoral letters, and open letters to the government. The secret police investigated me several times on suspicion of underground activities, but they found no evidence against me. No traitor was found in our group.

ZM: As a psychotherapist, do you see any possible psychological roots at work in the Catholic Church’s sex-abuse crises? Do you, for instance, see this as (at least in part) an issue of an unhealthy sexual repression on the part of the priesthood?

TH: Certainly the fact that many priests find it difficult to endure solitude and maintain sexual abstinence plays a role here. I think the time has come to put the obligation of celibacy back where it came from and where it makes sense—in monastic communities. The Catholic Church already has many married priests—Eastern Rite Catholic priests and former Protestant pastors.

ZM: When I talk to many of my Protestant friends and family, they are shocked that the Catholic Church is still so hung up on the ordination of women and married men. Why do you think we have been so slow to embrace these as legitimate forms of the priestly charism?

TH: I believe that the main arguments against the ordination of women are not theological, but cultural. I think most Catholics in Western countries, where equality between men and women is a given fact, would soon get used to women in the priestly role. It’s a bit different in some African and Asian countries where the understanding of gender roles is different. Decentralization of the Church and multi-speed reforms will probably be necessary.

ZM: What do you make of the phenomenon of “closed communion” in the Catholic Church? Do you see this, in any way, as a barrier to a more concrete ecumenism? As a priest, do you practice some form of “open communion” in your own parish?

TH: If the Church is to be truly catholic (universal), it must be ecumenical. I distinguish between “Catholicism” (denominational closed-mindedness) and authentic catholicity. I look forward to the moment when all Christians meet at the Eucharistic table of Jesus. In my pastoral practice, I respect the rules of the Catholic Church. These rules allow the Eucharist to be served to non-Catholics “in exceptional cases” when there is a “serious pastoral reason” to do so. I have asked my bishop for permission to judge when there is a “serious pastoral reason.” Experienced old priests can balance the paragraphs of ecclesiastical law with “pastoral reasons.” Studying textbooks on morals and canon law is helpful, but we must not forget the most important principle: Salus animarum suprema lex—the salvation of souls is the supreme law.

ZM: Could you share why you decided to title your new book The Afternoon of Christianity? What is meant by “afternoon”?

TH: Carl Jung used the metaphor of the course of the day to describe the dynamics of individual human life: childhood is the morning of life, then comes the midday crisis, followed by the afternoon, the age of maturity. I apply this metaphor to the course of the history of Christianity: the morning is the premodern period of building the Church’s institutional and doctrinal structures. Then comes the age of modernity, the age of secularization, the age of shaking up these structures. And our postmodern age is a call to “afternoon Christianity,” to greater maturity and depth.

ZM: In The Afternoon of Christianity, you challenge the popular “secularization” or “disenchantment” thesis, arguing instead that what we have witnessed in our age is a transformation of institutional religion into a more free-floating spirituality. In your view, how should the Church position itself with respect to this cultural phenomenon of the decline of institutional religion and the rise of spirituality?

TH: For a long time, the Church has emphasized doctrine (orthodoxy) and morality (orthopraxy) and fatally underestimated “orthopathy,” or spirituality, which is the sap of faith in the tree of the Church. Interest in spirituality has exploded repeatedly in the history of the Church, especially during crises in ecclesiastical institutions, and it has sometimes then fed reform movements, as it did during the sixteenth-century Lutheran and Catholic Reformations.

In our own time, the “marketplace of religious goods” responded to the thirst for spirituality ahead of the Church. It has flooded our world with a rich supply of esotericism, magic, occultism, and cheap imitations of Eastern spiritualities and ancient pagan cults. Therefore, careful spiritual discernment is needed in this field to avoid both the xenophobia of Christian fundamentalists and an uncritical superficial syncretism.

One must carefully distinguish the Zeitgeist, which is the superficial “language of the world” (public opinion, advertisements, ideologies, and the omnipresent entertainment industry), from the signs of the times (Zeichen der Zeit), which are the language of God expressed through events in the world, through profound changes in society and culture. The synodal way is the way of spiritual discernment. Right discernment is the fruit of a contemplative approach to reality.

In the epoch of modernity, Christianity has lost its cultural-political role as “religion” (religio) in the sense of integrating the whole of society (religio from religare, to bind together). Other phenomena have aspired to this role—to be the integrating force, “common language,” or “common worldview” over the last two centuries.

Synodal reform can prepare the Church for the cultural role of religion in another sense, in the sense of the verb re-legere (to re-read or read anew). The Church can be a school of re-reading and re-lecture, a new hermeneutic, a school of a new attentive approach to reality, a deeper interpretation of God’s speech, of God’s self-sharing. We must not succumb to the idea that we have already listened to and understood God’s self-sharing sufficiently.

ZM: Would your approach to the culture be different, then, from the “new evangelization” and Pope John Paul II’s approach to converting the culture? Do you think the new evangelization’s formulations for engaging with the world are still workable in today’s cultural climate?

TH: Evangelization is part of the ongoing mystery of Incarnation (incarnatio continua). The essence of evangelization is inculturation, a constant creative reinterpretation and recontextualization of the Gospel message in light of a changing cultural and social context. Evangelization without inculturation is merely superficial indoctrination. The “new evangelization” was a nice slogan, but I’m afraid there has been no real new evangelization. Many conferences have been held, a new dicastery has been set up in the Vatican, but it seems to me that it has remained just a lot of words and good intentions and few real results. Benedict XVI’s project to set up a “courtyard of the Gentiles,” a space for dialogue with agnostics, has had the same result.

The program of synodal renewal of the Church, announced by Pope Francis, is much deeper, offering a concrete, practical method of listening to one another and of “spiritual discernment” together. The art of “spiritual discernment” is the pearl of Jesuit spirituality and “synodality” is the experience of the first centuries of the Church.

ZM: You dedicated The Afternoon of Christianity to Pope Francis, “with reverence and gratitude.” I wonder if you might say something about what impresses you most about our current pope. Conversely, what criticisms do you have of his pontificate?

TH: Pope Francis is the great prophet of our time, one of the greatest popes in Church history. No one is doing more to build bridges between cultures than Pope Francis. His encyclical Fratelli tutti could play a role in the twenty-first century similar to that played by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the twentieth century. His call for the synodal renewal of the Church can mean much more than the transformation of the Church from a rigid clerical bureaucratic organization into a flexible network of mutual communication. Synodality (syn hodos) is a common journey: it is meant to renew, revive, and deepen communication, and not only within the Church. It is also about the Church’s ability to communicate with other systems in society, with other cultures and religions, with the whole human family, and with the planet we inhabit: to perceive the ongoing symphony of creation. It can also inspire the transformation of the process of globalization into a process of sharing and solidarity.

Criticisms? I regret a number of his unfortunate statements about Russia and the Russian-Ukrainian war. Unfortunately, he is surrounded by people who tragically underestimate Russian imperialism and naively believe that Putin—the Hitler of our time—will sit down for diplomatic negotiations before he is pushed to do so by force of arms. Not a word he says can be trusted. Supporting Ukraine is necessary for the security of the whole world.

ZM: What do you think are the pastoral and theological questions we need to get ahead of the curve on as we anticipate the years and decades ahead?

TH: We need a change in theological anthropology. We need to replace the medieval static understanding of “unchanging human nature” with a dynamic understanding of human existence as being in relationship. This will have implications for political and sexual ethics. The doctrine of the Trinity needs to be taken seriously—God is relational and created humans to live in relationships, to undertake the task of maturing and transforming ourselves by living with and for others.

ZM: Many Catholics in America—particularly those taken in by various internet apologist personalities—seem to attach great importance to proper doctrine without sufficient attention to both spiritual and ethical conversion. What might a Christian faith look like that is not over-attached to beliefs but that takes up faith also—or even primarily—as a way of being in the world?

TH: The synodal reform of the Church presupposes a deepening of spirituality and a reform of theological thinking: a shift from static thinking in terms of unchanging natures to an emphasis on the dynamics of relationships. At the center of the Christian understanding of God is the Trinity—God as a relationship. God created man in his image: our human “nature” is, therefore, to live in relationships, being with and for others; our mission is to share and communicate on a common path. The shift from thinking in terms of static, unchanging natures to an emphasis on the quality of relationships involves a renewal of ecclesiology, of the understanding of the Church, and of Christian ethics, including sexual ethics and political ethics. In making this shift, we cannot ignore the findings of the natural and social sciences.

The Church is to be a community of pilgrims (communio viatorum) that contributes to the transformation of the world and the whole human family into a community of the journey, helping to deepen the dynamics of sharing. The Church also has a “political,” prophetic, therapeutic, and transformative mission in the world. Church is a sacrament, a symbol, and an instrument of the unity to which all humanity is called in Christ. This unity is an eschatological goal that can only be fully realized at the “Omega Point” at the end of history, but for which we must continue to work throughout history.

ZM: What words would you impart to American Catholics following the reelection of Donald Trump? In what ways could American Catholics view national upheaval as an opportunity to become a deeper, more spiritual people?

TH: The victory of the amoral populist Donald Trump, a chaotic and immature personality, is a tragedy not only for America but for the whole world. Those who cannot accept defeat and are incapable of critical self-reflection, who don’t respect democratic rules and the culture of law, do not deserve to win and rule. When the people of Europe watch the narcissistic scenes of Donald Trump—whose gestures and facial expressions are strikingly reminiscent of Benito Mussolini—his vulgarities, his notorious lies, and his empty phrases, they laugh out loud. I don’t know if Trump voters realize that the world will not take America seriously with such a president. The spiritual blindness that makes this figure—who is the pure embodiment of values in complete opposition to the Gospel—into the object of a religious cult needs to be seriously studied. The attempts to turn the Christian faith into an ideological weapon for culture wars dangerously discredit Christianity. Nationalism and national egoism are contrary to catholicity.

Many forms of the Church today resemble the empty tomb. Our task is not to weep at the tomb and look for Jesus in the world of the past. Our task is to find the “Galilee of today” and there encounter the living Jesus in surprising new forms. We need to rediscover the depth and richness of Christianity, the polyphony of Scripture and tradition, and faith as a source of beauty, freedom, and joy.