The most interesting moment in Hugh Whitemore’s The Best of Friends—a play about the friendship between George Bernard Shaw and Dame Laurentia McLachlan, a cloistered Benedictine at Stanbrook Abbey—comes about a third of the way through. Shaw, returning to England after a visit to the Holy Land, has gifted Laurentia a small stone from Bethlehem. He picked the stone himself; before he gave it to Laurentia, he also placed it in a small, specially commissioned silver reliquary.

Shouldn’t the reliquary, a mutual friend inquires, be given “a brief inscription explaining its purpose and saying who it’s from”? At this suggestion, Shaw explodes:

What the devil—saving your cloth—could we put on it? We couldn’t put our names on it—could we? That seems to me perfectly awful. “An inscription explaining its purpose”! If we could explain its purpose, we could explain the universe. I couldn’t. Could you? … Dear Sister: our fingerprints are on it, and Heaven knows whose footprints may be on the stone. Isn’t that enough?

Shaw angrily resists the idea that the reliquary he’s given his friend is only an object like any other—at the same time, he doesn’t really want to ascribe to it any particular meaning. Why, then, does it matter quite so much? He doesn’t know; in a real sense, he doesn’t want to.

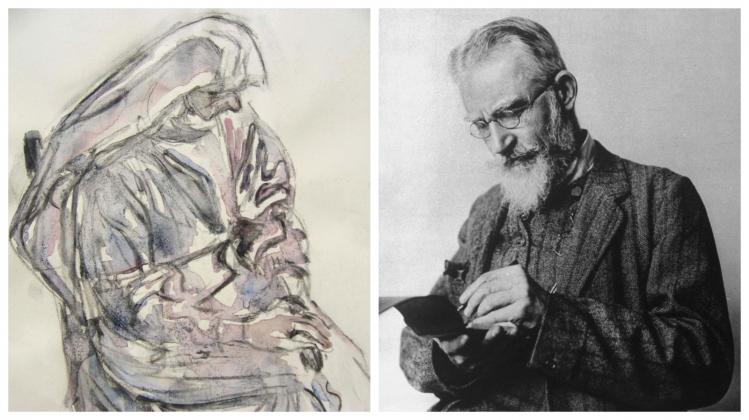

The Best of Friends is drama, but Shaw’s words are drawn almost verbatim from his correspondence with the real Dame Laurentia, as is almost all of the play’s dialogue. You can read it, along with other letters they exchanged and accounts of visits Shaw paid to Stanbrook Abbey, in The Nun, the Infidel, and the Superman, a book about Laurentia’s friendships written by a fellow nun there. Or you can pick up, if you are lucky enough to find it, the Masterpiece Theatre production of The Best of Friends starring Patrick McGoohan as Shaw, Dame Wendy Hiller as Laurentia, and Sir John Gielgud as Sydney Cockerell, director of the Fitzwilliam Museum and the “mutual friend” who elicits Shaw’s scorn for asking about the reliquary.

Though hardly a household name, Laurentia maintained an active correspondence with many of her secular contemporaries in the world of letters. Her research played an important role in the restoration of Gregorian chant, and she even received a commendation from Pius X for it in 1904. (It was this work that led her to become friends with Sydney Cockerell, and subsequently with Shaw.) She was, as Shaw said, “the enclosed nun with an unenclosed mind.”

It’s her friendships, however—not her scholarship—that have received the most sustained attention since her death. This isn’t too surprising; we are, after all, interested in the ability to maintain friendships across sharp differences and other obstacles (such as cloister grilles). Many of us disagree with people very dear to us on issues of the greatest importance; that Cockerell and Shaw, two atheists, could plausibly be described as “the best of friends” with a cloistered nun gives us hope.

But that friendship was more complicated—and for that reason more instructive—than any simple feel-good story. Shaw’s description of his friend as having an “unenclosed mind,” for example, is an interesting turn of phrase—clearly affectionate, but just as clearly backhanded. On what kind of terms, one wonders, did this friendship really exist?

Indeed, the further one reads about their friendship, the more one is not just impressed by the real depth of mutual affection that existed between them, but frustrated by Shaw’s refusal to respect Laurentia’s choice of life. His friendship with her was marked from the beginning by a kind of surprise that such a creature existed. After their first meeting, he was uninterested in seeing her again until he discovered that she had been in the convent for fifty years—as Laurentia admitted, “When he found that whatever I am is the result of my life here he was impressed.”

But why did he assume that a woman who had recently entered a cloister could only become less interesting, or somehow diminished? At times he felt openly sorry for her—wishing, for instance, that he could persuade her to take a leave of absence, slip into a short skirt, and set off with him to Damascus. They had one serious quarrel over a satire Shaw had written of the search for God; it was, Shaw claimed to her, a “purification of religion from horrible old Jewish superstitions.” When Laurentia was unimpressed by this defense, he wrote to her: “I know much better than you what you really believe. You think you believe the eighth chapter of Genesis; and I know you don’t: if you did I would never speak to you again.” But it would be a curious sort of a nun that read the Bible like Thomas Jefferson.

In her letters and in the play, Laurentia comes off as happy with her life and untroubled by doubt; no wonder her biographers and dramatizers alike find more to think about in the lives of her famous friends. She entered Stanbrook Abbey at the age of eighteen because she recognized that she could be happy there; as far as one can gather, she was. Shaw’s self-dramatizations (he claims to Laurentia his satire was divinely inspired), his flirtations with religion on one level and contempt for it on another—these are, from one point of view, more interesting than Laurentia’s steady faith.

But it’s precisely the commitment Laurentia maintains to her difference, to her own community and her own standards, that allows their friendship to exist at all. In the context of the cloister, Shaw’s pirouetting around the really difficult questions, his conviction that God will reward him more for refusing to believe than believing, comes off not as interesting, but as exhausting, even a bit sad. Why respond to putting your name on a reliquary as if it were sacrilege if you don’t think the object contained is sacred?

Laurentia can like Shaw, respect his work, and yet be unimpressed by him for a number of reasons, surely one of which is having firmly rooted herself in a life where Shaw can only matter as a person, not a personage. In the cloister, Shaw is just one visitor among many, and one more confused than most. Her special affection for him doesn’t change the way her life is built around an entirely different center than his. In The Best of Friends, the world that matters is Shaw’s world, not hers. She’s the one whose mind is always in danger as being perceived as enclosed.

That’s a regrettable error. “Oh, wasn’t this nun remarkable, since these very smart men were her friends” is the message, both in the play and in the book on which it’s based. But Laurentia’s real life, and thus any real sense of whether she was remarkable or not, exists quite outside their scope.

If there’s a lesson to be drawn here about how to cultivate a friendship over stark differences—and, given that we are dealing with two fairly odd individuals at some distance from us in time, there might not be—it probably starts there. We have to love each other, no matter how much we might hurt or mystify one another. In the eyes of God, no one matters more than anybody else, and for Christians—whether cloistered or not—keeping our distinctive love for even the best of our friends in line with this principle is necessary to love them at all. How lucky, after all, Shaw was to discover a friend for whom he was not especially intimidating, for whom he was not lovable because he was useful or intelligent or famous, but because he was an irascible soul in need of someone who could see through him.