Interested in discussing this article in your classroom, parish, reading group, or Commonweal Local Community? Click here for a free discussion guide.

Near the beginning of the Book of Jeremiah, the prophet waxes nostalgic over God’s love for Israel. “I remember the love of your youth,” he has God say. “Your love as a bride—How you followed Me in the wilderness, in a land not sown.” For Jeremiah, the wilderness is a honeymoon setting, a paradise of distilled spirituality and uncomplicated love.

Compare that with Bamidbar, the fourth book of the Torah (the Hebrew name literally means “the wilderness,” but in English it is called the Book of Numbers). In Bamidbar, the desert produces dreadful hunger and thirst, cowardice, fury, collapse, rebellion, all followed by plague, bloodshed, poisonous snakes, catastrophic defeat, and hopelessness.

These dueling accounts of the wilderness repeat throughout the Hebrew Bible, appearing most clearly through a literary technique known as “doublets.” The Torah tells some stories twice, with slight variations in setting or circumstance. Abraham pawns his wife off as his sister twice; Hagar flees Sarah twice; Jacob leaves home twice; Joseph is pulled out of the pit by two different wandering groups. For biblical scholars, doublets indicate different authors from different regions and traditions shading the narratives in accordance with different agendas. Since the redactor included both versions of events in the final version, the careful reader develops a complex attitude toward some of the Bible’s most important stories.

For example, in Exodus (16:2–14), the Israelites grow hungry in the desert. This leads to false memories of “flesh pots” and bountiful supplies of bread in Egypt. God quickly responds by promising to “rain down bread from the sky,” while Moses mildly rebukes the people for their temporary loss of faith. God “hears” the further complaining and sends a flock of quail so his people can eat meat.

But the parallel story in Bamidbar (Numbers 11:4–34) paints a very different picture. The wandering Israelites moan to Moses, “We remember the fish that we used to eat free in Egypt, the cucumbers, the melons, the leeks, the onions, and the garlic. Now our gullets are shriveled. There is nothing at all.” Instead of a mild rebuke, Moses now responds with a despairing, suicidal rage, begging God to take his life. In abject fury, God promises to give the people meat “until it comes out of [their] noses.” He sends poisonous quail and thousands perish in a plague.

Similarly, there are two different stories of Moses bringing water from a rock. In the Exodus version (17:2–7), the people grumble that they’re thirsty. God instructs Moses to take the staff he used to part the sea and strike a rock. Water emerges; the people drink. Once again, God hears human suffering in the wilderness and responds lovingly. Meanwhile, in Bamidbar, things go much the same way until God mysteriously punishes Moses once the water flows. He will not be allowed to fulfill his lifetime mission of guiding the people into the Promised Land.

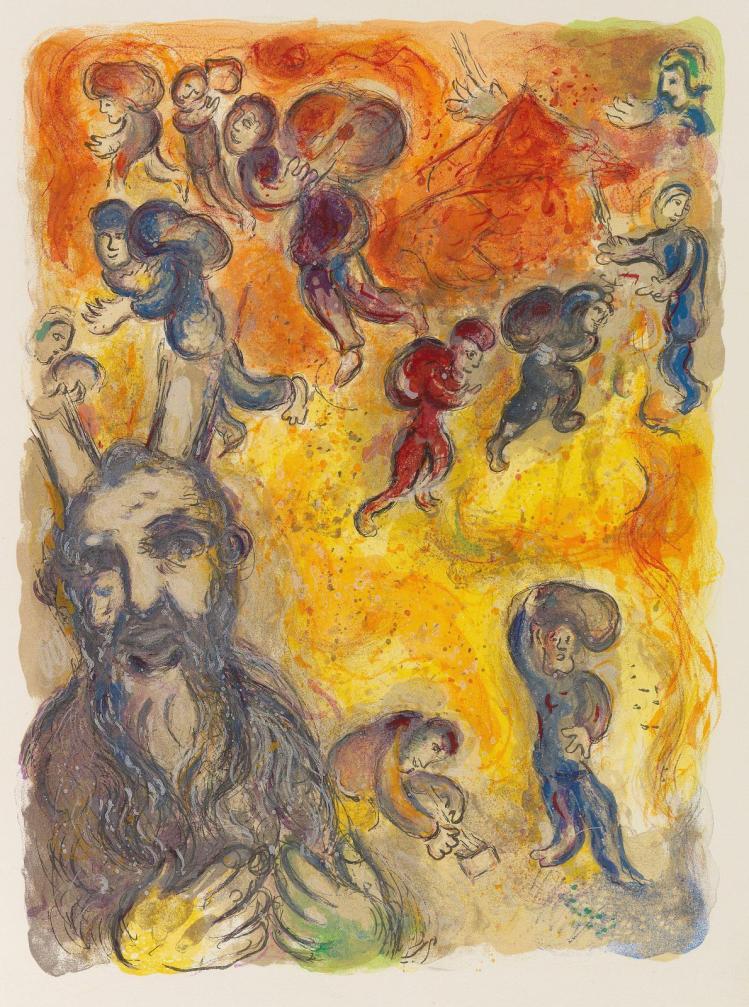

For millennia, readers have struggled to understand this punishment. Was it because Moses called the people rebels before he hit the rock? Should he have spoken to the rock instead of hitting it? Is God furious because Moses failed to give him credit? The fact is, there is no satisfying justification for Moses’ punishment in this version of the story. God’s will is as arbitrarily harsh as the author’s depiction of the wilderness. It’s unforgiving, relentless, dangerous, furious.

In these doublets and others (see, for example, Numbers 10:29–32 and Exodus 18:17–27) we are likely encountering the work of at least two different authors. But we also begin to discern two distinct attitudes toward the wilderness, and more generally toward the ideal of wandering versus the urge to build a home and stay put. One author cautions that nomadic life is filled with scorpions, snakes, hunger, thirst, weak leaders, and an angry, unforgiving God. The other author, like Jeremiah, reassures prospective wanderers that God protects his people, provides them with what they need, and communes with them directly and lovingly in the wilderness.

It’s reasonable to interpret these two authors as representing the two distinct approaches to Babylonian exile after the destruction of the First Temple in 586 BCE. Jeremiah urged the people to give up the fight and go into exile, but the journey to Babylonia involved wandering through the desert. Our pro-wilderness author responds with pro-wilderness narratives, while the anti-wilderness author warns against leaving and insists that the exiles will get no help from God in their wanderings. Better they stay put, rooted in their land, their Temple, their Holy City.

But these attitudes involve more than a single political disagreement. The conflicting stories bear on a debate over the very essence of post-temple Judaism. Jon D. Levenson demonstrates this clearly in his book Sinai & Zion: An Entry into the Jewish Bible. Levenson argues that much of historic Judaism hinges on a tension between two mountains. Sinai, where the Israelites received the Ten Commandments, represents the wilderness. It’s a place where the Israelites experienced God directly, where, as later rabbis would imagine, every individual received a unique vision of God. Since, even now, there’s no clarity about where exactly this mountain is located, it evokes a sense of wandering, of journeying aimlessly in the desert, waiting faithfully for God’s voice. Mt. Zion, on the other hand, symbolizes rooted sacred space. It’s the permanent location of the Temple, situated in the heart of Judaism’s sacred city. Zion is urban; Sinai is desert. Zion is institutional; Sinai, personal. Zion, with its Temple bureaucracy, offers worshippers a mediated spiritual experience; Sinai offers direct access to God.

Which is genuine Judaism? The Torah argues both sides. When Abraham and Lot decide to go their separate ways, Lot chooses the city—Sodom. Abraham chooses the desert and lives a nomadic life. The subsequent destruction of the wicked Sodom makes it clear that Abraham made the right choice, the moral choice. (Interestingly, Jeremiah often refers to Jerusalem as “Sodom.”) On the other hand, the entire book of Deuteronomy argues against wandering. In several passages, God, through Moses, commands the people to worship exclusively at one central location. Solomon builds that central institution: a Temple in Jerusalem. The Judean monarchs in the Book of Kings are judged according to how successful they were in centralizing worship—that is, in discouraging the people from adopting a nomadic spirituality.

But history gets its own say in ideological debates, and for much of Jewish history, wandering wins out. After 70 CE and the destruction of the Second Temple, the Jews became an exiled nation, praying for God’s protection in foreign lands, suffering expulsions, and postponing the planting of roots until the arrival of the Messiah. Like Abraham, Joseph, Moses and the Israelites, Jews wandered, and exile defined the Jewish character.

And then history intruded again. European antisemitism culminated in the Holocaust and demonstrated conclusively the dangers of the wilderness. Without roots in a particular place, the Jews were left defenseless, even more so than the wandering, starving, suffering biblical Israelites. From 1939 to 1948, Jews experienced in dizzying succession both the worst nightmares of wandering and the absolute, existential necessity of rootedness. The result was a shift in Jewish religious consciousness from Sinai to Zion, from wilderness to homeland.

And so it has stood for all of my sixty-three years. Judaism, for my generation, is a religion rooted in specific places: the Land of Israel, Jerusalem, the Kotel, Mt. Zion. After centuries of harsh wandering, the Jewish people have returned home. It’s impossible to imagine the Judaism I learned, embraced, and taught for more than fifty years as something apart from our spiritual center which is located in a specific place—the State of Israel.

But I’m beginning to notice a change. Like many Jews, I was surprised that the rhetoric of many of the demonstrations I saw after October 7 seemed to extend past particular Israeli or U.S. policies and target the very idea of Israel as a Jewish state. The ubiquitous slogan “From the river to the sea” is not a critique of Israel’s occupation of the West Bank, nor is it a call for heightened humanitarian aid in Rafah. Despite the insistence of some protesters that they mean nothing more by the phrase than a call for peace and equal rights for Palestinians, it’s hard to see how it doesn’t entail the elimination of Israel as a Jewish state. A generous interpretation of the slogan (there are less generous ones) is that it rejects the idea that Judaism needs its own particular space in order to survive. In fact, according to the slogan, the Jewish yearning for rootedness in space is harming another people. Jews, therefore, should go back to wandering.

This idea is not only coming from young, non-Jewish demonstrators. A few Jewish thinkers are beginning to explore a “Diasporic” Judaism, a wandering Judaism without Israel. The novelist Philip Roth explored the idea with tongue (mostly) in cheek in his novel Operation Shylock: A Confession. Shaul Magid makes a more serious case in his latest book, The Necessity of Exile: Essays from a Distance. He asks his reader “to consider the price of diminishing or even erasing the exilic character of Jewish life.” He seeks to reclaim a “non-Zionist,” “wandering,” “Diasporic” Judaism with “a new relationship to exile as a productive motif for rebuilding a humble and non-proprietary Jewish relationship to the land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea.” Magid’s pro-exile argument no doubt represents a minority of American Jewish opinion. Still, his book was recently featured in the New Yorker and, as he rightly points out, polls show a rising number of Jews thirty-five and younger with little or no attachment to the State of Israel.

The obvious response to Magid—or to young, alienated Jews, or anti-Zionist demonstrators, or, for that matter, to Jewish West Bank settlers drunk on biblical rootedness—is that two voices call out from the Torah. There is the Sinai thunder of the wilderness, but there is also the urban clamor from the heart of Jerusalem. Exile and wandering seemed sufficient, even necessary, until much of the world turned on the Jews. But radical rootedness could lead to Jewish settlements in Gaza and endless war. Clinging to space closes off any hope for peace, while exile exposes the Jews to the dangers of the Diaspora.

To wander or stay put? Which is the correct decision, the true voice? The Torah, in its strange wisdom, refuses to decide.