Soul music. The blues. Gospel. Jazz. All can be traced back to the same source, which is the experience of Black people in America, the oppression and triumph, the joy and ache, the struggle to make sense of it all. The international appeal of Black music is a testament to the humanity at its core, the celebration of life in all its bittersweetness.

“Bittersweet” may be the single best word to describe Ahmir Khalib “Questlove” Thompson’s documentary Summer of Soul, comprising footage from the Harlem Cultural Festival, a series of free outdoor concerts held in Mt. Morris Park (now Marcus Garvey Park) in the summer of 1969. The concerts, which drew around three hundred thousand people over six weekends, were organized by the energetic promoter and former lounge singer Tony Lawrence, “a hustler in the best sense” who “talked a big game and delivered,” as one person describes him. This spellbinding documentary includes commentary from attendees as well as famous figures, including journalist Charlayne Hunter-Gault and activist and media personality Al Sharpton. Despite early efforts to market the professionally filmed recordings of the concerts, the footage sat undiscovered in a basement, according to the filmmakers, for half a century; it is now being shown to audiences for the first time. The result is the best kind of time capsule, one that demonstrates how much American life has changed, how much remains stubbornly, depressingly the same, and how timeless the power of great music is.

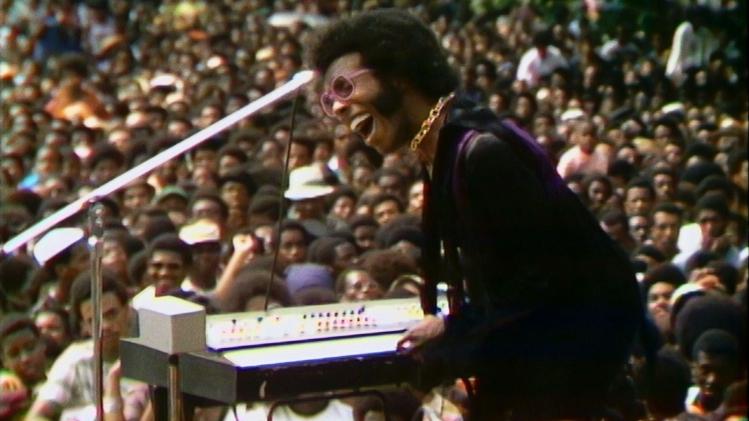

The music! Stevie Wonder was there, all of nineteen years old, singing, playing drums and keyboards, and generally leading us to, well, wonder at the concentration of so much talent in one human body. Nina Simone was there, in all her otherworldly regality. Sly and the Family Stone—despite their reputation for showing up for concerts hours late or not at all—were there, right on time, as was their infectious soul-rock, with its message of inclusiveness. That preeminent bluesman B. B. King was there, and so were Gladys Knight and the Pips, and the Fifth Dimension, and the Staple Singers, and Mahalia Jackson, and the drummer Max Roach and his wife, singer Abbey Lincoln, and many others. And the crowds were there, too, many thousands of mostly young African Americans, some of them children, taking part in what one attendee, a young boy at the time, called “the ultimate Black barbeque,” one that “smelled like Afro Sheen and chicken.” It was the “summer we became free...from our parents,” recalls one commentator, a college student in 1969.

It was the summer of many things, and Summer of Soul does a good job of placing the concerts in historical context. The Harlem Cultural Festival coincided with the first moon landing, and the documentary includes person-on-the-street interviews about that historic event, revealing gaps between Black and white perceptions of reality that have yet to be bridged. The whites interviewed saw the landing as a wondrous achievement; the Blacks thought the money for the space program would have been better spent feeding the hungry down here on Earth. This was also the year when a new consciousness was emerging for African Americans, a new defiance and self-celebration—a time “when the ‘Negro’ died and ‘Black’ was born,” as one observer puts it, when straightened hair and neckties gave way to Afros and dashikis. Driving that point home, Hunter-Gault tells the story of when a white editor that year changed the word “Black” to “Negro” in the headline of her New York Times story. It prompted her to write the paper an indignant eleven-page memo, after which the Times’s use of “Black” became official. That change took place against a backdrop of Black activism and protests against the war in Vietnam. Finally, a couple of hours north of Harlem, four hundred thousand or more people attended the concerts at Woodstock, performances that have eclipsed the Harlem Cultural Festival in historical accounts of the era.

But if the Harlem concerts were insignificant, somebody forgot to tell the attendees, a handful of whom reflect touchingly on what the event meant to them. Also touching are the expressions on the faces of the present-day, incredibly well-preserved married couple Marilyn McCoo and Billy Davis Jr., formerly of the Fifth Dimension, as they watch footage of their younger selves performing. Dressed in bright orange outfits, the group sang “Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In,” their monster-hit version of the song written for the Broadway musical Hair. As McCoo explains, many thought—based on the group’s sound—that the Fifth Dimension was white, and so it meant a great deal to her to perform for such a large gathering of Black folks.

The presence of the Fifth Dimension was just one example of the variety of music and musicians the concerts encompassed. Gladys Knight brought her mighty, insistent voice to her signature cover of “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” with the Pips supplying backup vocals and their inimitable choreography; the free-jazz underground hero Sonny Sharrock held his electric guitar sideways and at neck level, the better to squeeze out of it sounds that no one else could, high and fast and seeming to flirt excitingly with loss of control; lean, tall, Afroed David Ruffin of the Temptations sang the Motown group’s hit “My Girl,” showing off a range from cellar depths to the ionosphere; a young, fierce Hugh Masekela, in a sleeveless, dark-gray zippered outfit, blazed a trumpet-line path through his highly popular “Grazing in the Grass”; and B. B. King, sweating in his jacket and tie, big rings on his fingers, underscored the tell-it-like-it-is lyrics of “Why I Sing the Blues” (“When I first got the blues / they brought me over on a ship”) with a strong, nimble, ringing guitar. The variety on display was not only musical but cultural. The Cuban-born percussionist Mongo Santamaria and Puerto Rican–born bandleader Ray Barretto were on hand, too, giving the crowd a message of togetherness and a shot of Latin rhythms. As Lin-Manuel Miranda notes, “Mongo Santamaria, at this festival at this time in Harlem in the ’60s, is the nexus of the Black and Brown communities that make up uptown New York.” His music, Miranda added, is “where Cuban music meets jazz.”

The miracle Summer of Soul reveals is the sense of unity in diversity, the way that all of the different sounds connected. Billy Davis, who had sung gospel as a teen, slipped some of that feel into the hippie vibe of “Let the Sunshine In.” This idea of different sounds coming together may have been best expressed by Mavis Staples of the Staple Singers, the gospel-come-soul group made up of Roebuck “Pops” Staples and his three daughters. “People thought we were old people” based on their gospel work, she recalls, and yet she remembers asking Pops, “Why are these people inviting us to blues festivals? We don’t sing no blues.” Her father replied, “Mavis, listen to our music. You will hear every kind of music in our songs.” Indeed, she muses, “It was years before my sisters and I knew Pops was playing blues in his guitar while we were singing gospel.”

Mavis features prominently in the most jaw-dropping moment in all of Summer of Soul. Six years earlier, Mahalia Jackson had sung at the March on Washington; now, with the wound of Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1968 assassination still fresh, she appeared at the Harlem Cultural Festival to sing King’s favorite gospel song, “Take My Hand, Precious Lord.” As Mavis recalls, Mahalia whispered to her onstage, “Baby, Mahalia don’t feel too good today. I need you to help me sing this song.” Mavis, who called Mahalia “my idol,” started things off, sustaining throaty high notes as the song and the crowd moved her to jump and shake her head. Then Mahalia was ready. She may have been singing about—and to—the Lord, but her voice commanded the earthy power, the unstoppable natural force, of the bygone-era blues shouters Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith. Yet Mavis, brought back to the mic by Mahalia, held her own in a call-and-response with the gospel great as the crowd clapped, shouted, and screamed its approval.

As great as the music is, Summer of Soul does not gloss over how tough things were in 1969, in the country as a whole and in Harlem in particular, and how fiercely some responded to what was going on. In America’s Black capital, poverty and joblessness were rampant, as was a heroin crisis; then as now, young Black men were falling to police bullets and nightsticks. African Americans wanted change. (One attendee muses, “The goal of the festival may very well have been to keep Black folks from burning up the city in ’69.”) The people who showed up for the concerts were “radicalized,” as the cultural critic Greg Tate puts it, and others did not stop at singing along with soul hits. “When we kicked off the Young Lords Party in New York, we were in complete harmony with the Black Panthers,” recalls Denise Oliver-Velez. (The Panthers provided security for the Harlem Cultural Festival.) “As activists, we were making a complete and total commitment. It was like going to war. And we were propelled on a wave of music.”

That seems like the biggest difference between today and the era captured in Summer of Soul: the sense, then, that music could inspire change. Perhaps that sense came from the feeling that gods mixed among us. At a time when music groups had long been segregated by color and gender, Sly and the Family Stone—“a game-changer on so many levels,” in Tate’s words—was a soul group, led by a Black male, with female members (including a trumpeter) and, hold on a second, a white drummer; they almost didn’t have to sing the words to their hit “Everyday People” to get the message across. And then, good Lord, there was Nina Simone. In a bright yellow patterned dress, gigantic earrings, and a black wrap that funneled her mass of hair back in a kind of soul-cone, she sang “Backlash Blues” and “To Be Young, Gifted, and Black” in her signature tone, “somewhere between hope and mourning,” as Sharpton puts it, one that “defined a whole generation” and in which “you could hear our pain but [also] our defiance.” Hunter-Gault knows something about this, recalling, in 1961, being one of two Black students to integrate the University of Georgia. White girls routinely stomped on the floor above her dorm room to rattle her, but in the face of such hate, she listened to Nina Simone records and felt at peace. If there is a stronger testament to the power of music, of Black music, I have yet to hear it.