I learned about the case of Curtis Flowers, a black man who has been tried six times for the same crime, through the excellent reporting of the investigative podcast In the Dark. For the show’s second season, American Public Media host Madeleine Baran and her team of reporters went to Winona, Mississippi, to find out why Flowers was accused of murdering four people in a small-town furniture store in 1996, and why he has spent twenty-one years in prison awaiting trial after trial. Four guilty verdicts have been thrown out due to prosecutorial misconduct (the other trials ended with deadlocked juries). And each time, Flowers was tried by the same district attorney, a man named Doug Evans.

Baran has a longstanding professional interest in issues of power and accountability—she exposed a cover-up of clergy sexual abuse in Minneapolis–St. Paul while working at Minnesota Public Radio. And in the story of Curtis Flowers, her team found alarming lapses everywhere they looked. Each aspect of the prosecution’s case—police record-keeping, witness statements, handling of evidence—was called into question. One crucial episode lays out damning evidence that Evans deliberately eliminated black jurors from Flowers’s trials.

In 2007, the Mississippi Supreme Court found that Doug Evans had done just that in Flowers’s third trial, in violation of the 1986 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Batson v. Kentucky. The conviction was overturned, but Evans was not penalized. Three trials later—after Flowers was sentenced to death in 2010, and following In the Dark’s dogged investigation—an appeal alleging Evans had committed another Batson violation brought Flowers v. Mississippi to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In June, the court overturned Flowers’s conviction with a 7–2 ruling. Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote, “The State’s relentless, determined effort to rid the jury of black individuals strongly suggests that the State wanted to try Flowers before a jury with as few black jurors as possible, and ideally before an all-white jury.”

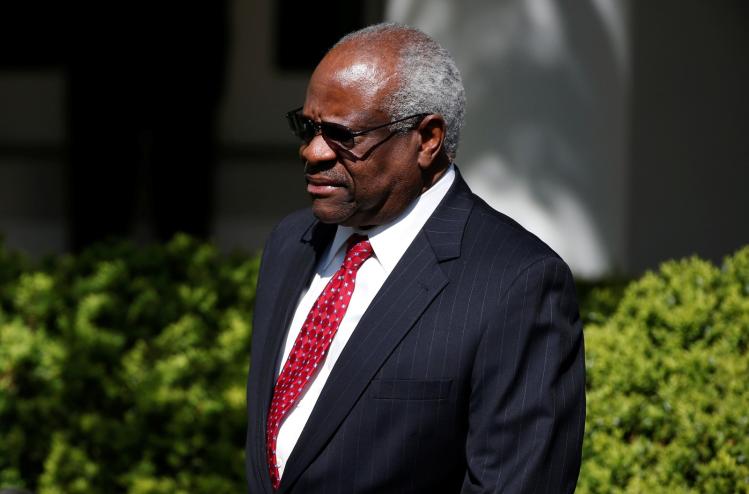

Clarence Thomas dissented (along with Neil Gorsuch), which itself was not surprising. But his dissenting opinion took a disgraceful swipe at the media that went beyond right-wing boilerplate. Thomas speculated that the Supreme Court heard Flowers’s appeal only “because the case has received a fair amount of media attention,” a mistake that, in his view, “only encourages the litigation and relitigation of criminal trials in the media, to the potential detriment of all parties—including defendants.” Quoting an older opinion of the court, he added, “The media often seeks ‘to titillate rather than to educate and inform.’ ”

Some “true crime” reporting does aim primarily to titillate. No one could fairly say the same about In the Dark. The podcast describes but does not revel in the details of the crime, and it treats its subjects with compassion. It examines the murders from every angle, with a focus on the people most affected, from the victims’ grieving families to Flowers’s steadfast parents. It holds the evidence against Flowers up to the light and sifts through public records to establish patterns of misconduct. Its painstaking, humane approach to uncovering injustice is a sterling example of what public media is for.

When In the Dark took up his story, Flowers had been in prison for twenty-one years. “Could the attorney general have said, you know, enough already?” Justice Samuel Alito asked during oral arguments, wondering why the state never intervened, even after Evans was found to have violated the Constitution. The answer he received was that the state could intervene only if asked to do so by the district attorney. In other words, no one but Evans could take Evans off the case.

The “media attention,” then, did precisely what it should. In the Dark educated and informed. It exposed flaws in a justice system that cannot police itself. Citing concerns about defendants’ rights, Thomas says, “Any appearance that this Court gives closer scrutiny to cases with significant media attention will only . . . undermine the fairness of criminal trials.” But Flowers’s case is most noteworthy for having escaped scrutiny for so long. It is hard to imagine the defendant being treated less fairly in the wake of this rebuke—even though, as Thomas notes with satisfaction, “the State is perfectly free to convict Curtis Flowers again.”

Thomas’s attack on the media is more than obtuse; it is irresponsible and dangerous. In the era of President Donald Trump, who constantly threatens the freedom of the press and angrily resists accountability, our system of checks and balances is performing as poorly at the federal level as it did in Mississippi. Strong, independent journalism is desperately needed. A world where no one outside of Winona ever learned about Curtis Flowers and his six murder trials would not be more just. It is demoralizing for a Supreme Court justice to argue otherwise.