I once had a job in which I taught adults how to notice and break counterproductive or destructive habits of thought or behavior. One question I liked asking people who felt stuck was “If someone could see you, what would they guess you were trying to do?” I still ask myself this question, and it jars me loose from some embarrassing things. I say I’m working on a piece of writing, but it appears that I’m checking to make sure nothing new has been posted online in the past three minutes. I say I’m trying to solve a baking problem, but it appears that I’m coming up with a list of reasons it was impossible to solve anyway. I say I love God, but it appears that my time with him is always my most negotiable—he never complains when I blow him off!

In You Are What You Love, James K. A. Smith is most concerned with that last one: the mismatch between our spiritual intentions and our daily habits. He wants to awake his readers to all the little choices that don’t even feel like choices but lead us to put God last in our lives.

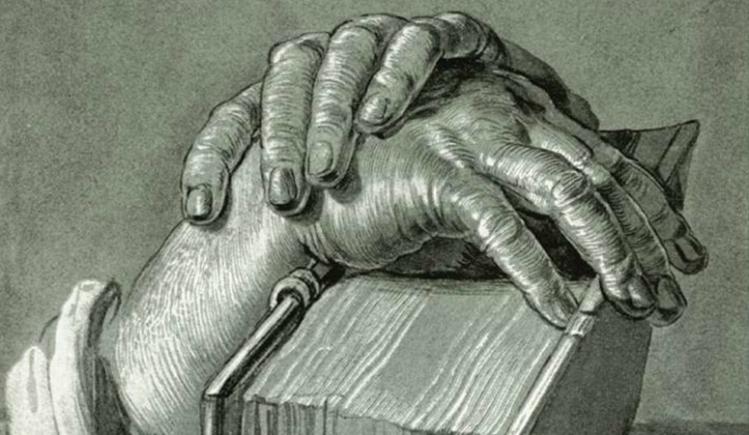

In Smith’s diagnosis, one of the ways we neglect God is by refusing his humblest gifts. We might meditate on the readings at church, do a little devotional reading at home, and keep tabs on blog posts online, but we run the risk of “approach[ing] discipleship as primarily a didactic endeavor—as if becoming a disciple of Jesus is largely an intellectual project, a matter of acquiring knowledge.” This chimes with my own experience. As a convert, I had to get out of the habit of only thinking about God and not actually praying and thinking with God. To read, analyze, and discuss can be fruitful, but to do only these things would be a lot like wooing your beloved by reading and writing about courtship but leaving out all the small affectionate touches, texts, and trivial traditions that keep you present in each other’s lives. It’s the boring things that ground a relationship. But, as Smith writes, “too often we look for the Spirit in the extraordinary when God has promised to be present in the ordinary. We look for God in the fresh and novel, as if his grace were always an ‘event,’ when he has promised that his Spirit faithfully attends the ordinary means of grace—in the Word, at the Table.”

Clearing space for God at the beginning of our days or even just at the beginning of a specific task within the day gives us the chance to accept the graces and guidance that God is always offering. An example: I try to pray Morning and Evening Office as bookends to my work day; it’s a way of tucking my whole job into a prayer. On days when I don’t really live up to that ideal, prayer at the end of the day can break me out of whatever rut I’ve settled into and point me back toward God.

Smith writes about how he created one potent ritual of beginnings by accident, when he felt bad for the students taking his 9:00 a.m. class. He made them a promise that he would have coffee available five minutes before class, so that they could get their caffeine fix without making a harried stop on the way. Keeping that promise prevented Smith from beginning class frantically himself. He no longer had the option to work till the last minute; he had a hard stop he was forced to respect. Almost any preclass ritual might have won him this peace, but the particular act of preparing coffee helped him find an answer to the question he assigns to parents in his book: “We tend to treat our children as intellectual receptacles, veritable brains-on-a-stick…[b]ut what does it look like to parent lovers? What does it look like to curate a household as a formative space to direct our desires? How can a home be a place to (re)calibrate our hearts?”

As a teacher, Smith also wrestled with the temptation to think only of his students’ intellect, but making coffee for them forced him to think about the needs of their bodies. And, in the time that physical care required, he found himself invited to care for them spiritually. He began praying for his students while the coffee brewed. His classroom became “a space for the students to be welcomed into.”

ONE THING THAT keeps us from making ourselves truly available to others or to God is the fear that we might not have enough to offer or a pride that prevents us from offering something humble. I often find myself tempted to put off a small prayer now in order to pray “better” later. If I’m a little tired now, if I feel tetchy, not holy, wouldn’t it be better to push aside God’s call to me until I can answer it with a little more dignity? This kind of logic always fails when we ask ourselves if we would treat anyone other than God this way. Would I push away a toddler asking for a hug because I felt my embrace would have more oomph later? Would I not kiss my fiancé hello because it’s a much shorter kiss than others we might share? The immediate need of a child or a lover helps one respond without delay, but God doesn’t need us. And, Smith says, we can put ourselves off prayer by trying to limit ourselves to the kind of original, expressive prayer that we could pretend was needed. As Smith writes:

If I worship in order to show God how much I love him, I might start to feel hypocritical if I just keep doing the same thing over and over and over again.... And so we need to find new ways to worship, new ways to show our devotion, fresh new forms to express our praise. Novelty is how we try to maintain the fresh sincerity of worship that is fundamentally understood as expression.

When I first started reading Scripture regularly, I found it a struggle. I was always trying to read in this expressive vein—almost the way I’d read in preparation for writing a college paper, looking for something novel to add to the corpus of scholarship on the topic. But the only thing that God wants us to give him is our whole selves. Each moment of self-gift allows us to consecrate more of our lives to God. The small, humble prayers that Smith commends, which aren’t inhibited by the fear of having nothing new to say, allow God to express his grace through us. That is finally the only expression that matters.