1920s

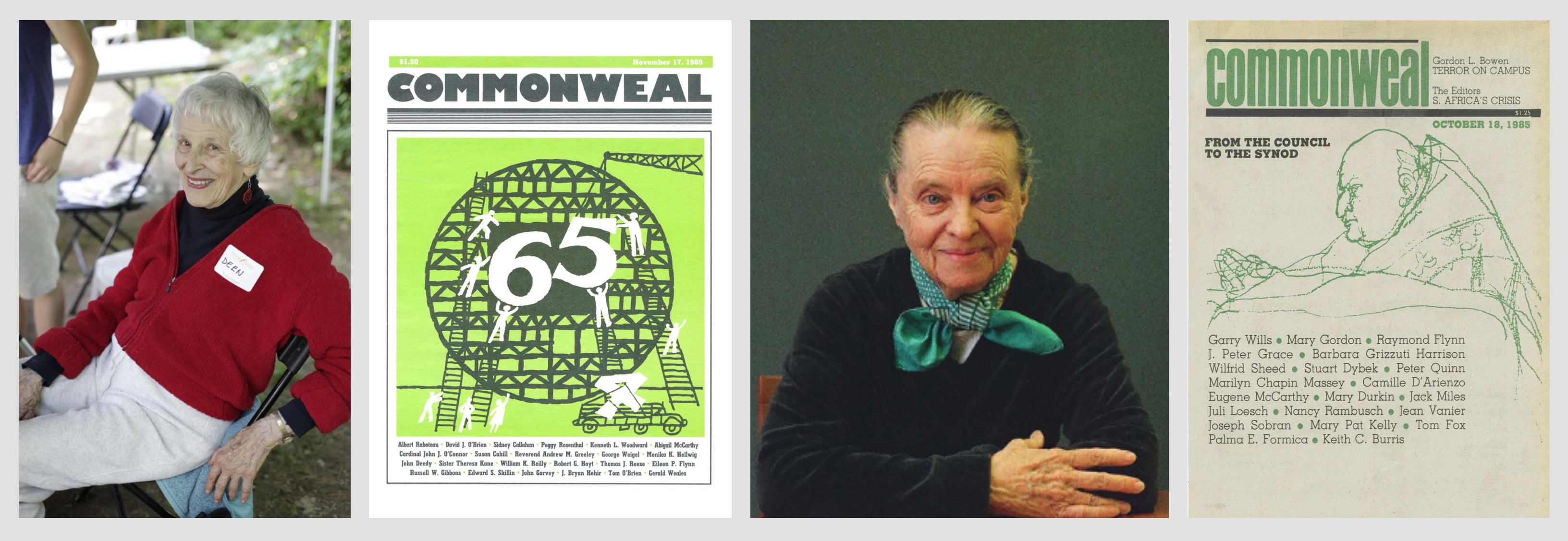

The Commonweal’s first issue was published in November 1924, a year after Time was first published and just a few months before The New Yorker was born.

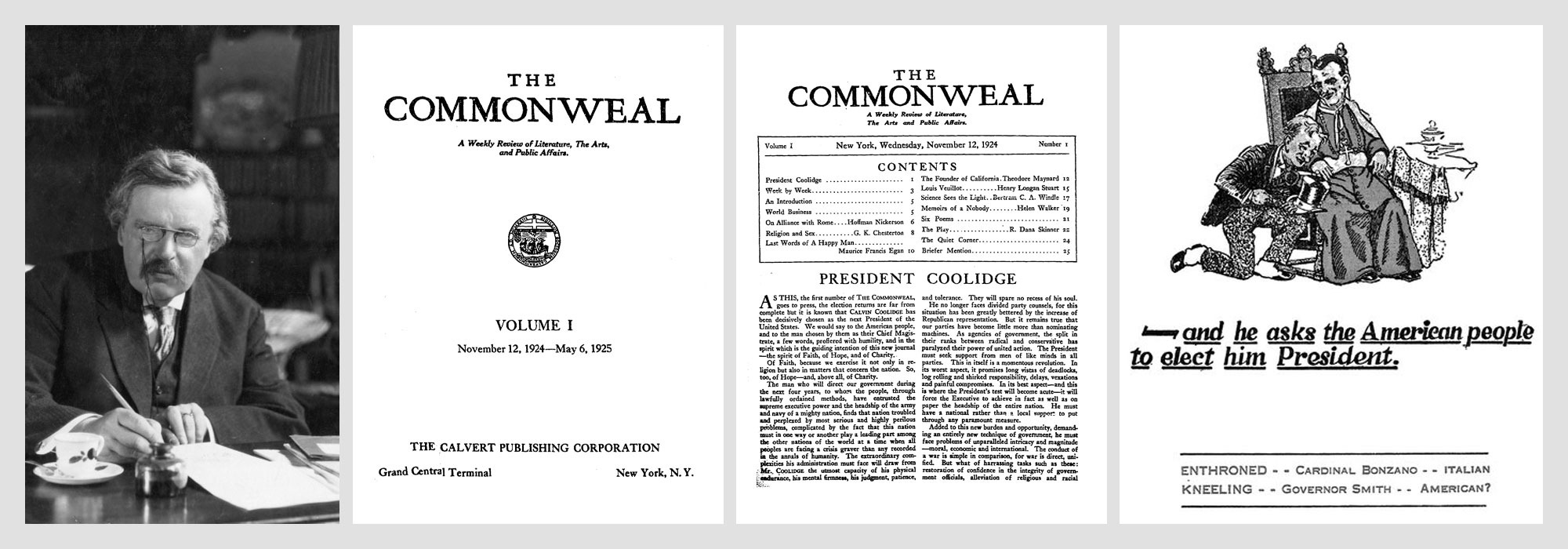

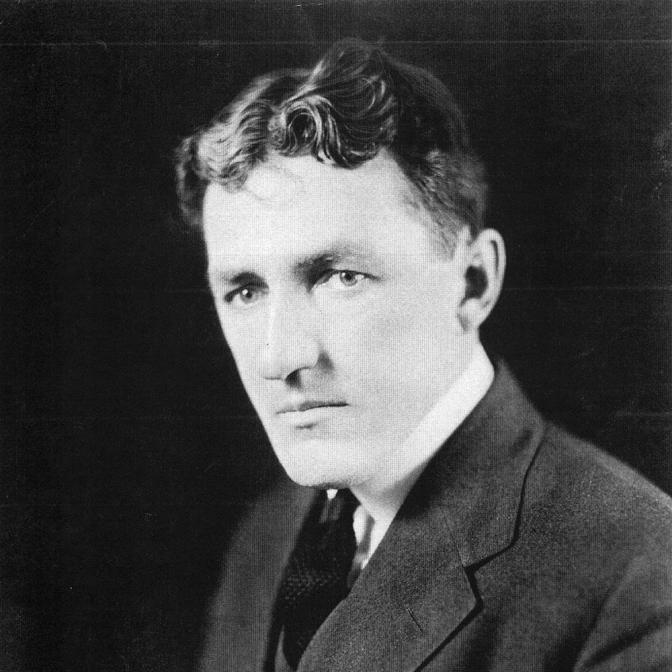

Founding editor Michael Williams was a Canadian-born journalist with a colorful past. After multiple newspaper jobs, a period in a failed Utopian commune and resettlement in California, he experienced a reconversion to Catholicism, which he later described in his The Book of the High Romance. While working for the National Catholic War Council, he conceived the idea of founding his own intellectual weekly: “How can Catholic thought, the Catholic outlook on life and the Catholic philosophy of living, as distinct from what might be called the Catholic inlook and individual religious experience, be conveyed to the mind of the whole American people?”

Williams found backing through the Calvert Associates, a group of (mostly) Catholic establishment business leaders and academics, including architect Ralph Adams Cram; Fr. Lawrason Riggs of the Washington banking family, later Catholic chaplain at Yale; and John J. Raskob, financial executive and builder of the Empire State Building. From the beginning, the magazine struggled with profitability, and required regular, sometimes urgent infusions of support. “It is,” said Thomas Woodlock of The Wall Street Journal, its first president, “an adventure, not a business enterprise.”

Further, the Calvert Associates set as their goal something more than publishing a review. They founded local gatherings of Associates to perpetuate Calvert ideals, especially religious understanding and liberty. They arranged for radio appearances by Commonweal editors and published a series of Calvert books on Catholic apologetics.

Editorial highlights

Should a Catholic Be President? (on the candidacy of Governor Al Smith) (April 13 1927)

G. K. Chesterton on Sex, from the first issue

Michael Williams covering the Scopes trial in Dayton, Tennessee (August 5 1925)

Because of its lay independence and ecumenical list of contributors, The Commonweal would shortly be known as a “liberal” Catholic weekly, but that would probably not be accurate by later standards. “It was,” wrote historian Rodger van Allen, “rather defensively and triumphalistically Catholic.” In its first weekly issue, it spoke of the Petrine Rock as that force which would resist pagan hedonism, and declared that “upon that Rock The Commonweal stands.”