Pope Francis has made it plain on numerous occasions that he doesn’t like “casuistry”—the case-based method of moral reasoning that has been a hallmark of Catholic teaching for centuries now. What is casuistry, anyway? And why doesn’t the pope like it?

Within the Catholic tradition, casuistry has its roots in the sacramental practice of confession. Confession has always been important for Catholics. But after the Fourth Lateran Council (1215), many Catholics were required to “make their Easter duty”—to take Communion during the Easter season. Since it was forbidden to receive Communion in a state of mortal sin, fulfilling that duty required Catholics to go to confession. Once there, they were required to confess to a priest each individual sin they committed, as well as the number of times they committed it. So the demand for good confessors increased exponentially. The priest hearing the confession was required to listen to the sins, evaluate their seriousness, and administer a penance designed both to punish and heal.

But how was the priest to know what to do or say in response? How was he to know whether an act confessed by a penitent was indeed a sin, and if so, how serious a violation of God’s law it was? To provide guidance, a genre of literature known as the “manuals of moral theology” developed, which provided a taxonomy of sinful actions, usually under the rubric of the Ten Commandments. They considered the range of possible sins in great detail.

The manuals were a type of professional literature written by priests for priests, not for laypeople. They were composed in Latin, not the vernacular, well into the twentieth century. (Even after the switch to the vernacular, some manuals kept the parts about sexual sins in Latin.) They were focused on what not to do on pain of mortal or venial sin, not what to do in order to grow in virtue. The manuals were no more designed to provide a broadly accessible and inviting view of Catholic life than the federal penal code was designed to inspire patriotic commitment to American life. They had a narrow purpose. At the same time, it is fair to say that they had a disproportionate—and distorted—effect on the moral imagination of the hierarchy as well as that of ordinary Catholics.

Pope Francis’s recent criticisms of casuistry, in my view, helpfully point to these distortions. Many of his most trenchant remarks have been given as part of his reflections during Mass at his residence, the Domus Sanctae Marthae in Rome.

In 2014, the pope suggested that casuistry is inimical to faith. According to a L’Osservatore Romano summary of one of his morning meditations, he claimed that

“Casuistry is precisely the place to which all those people go who believe they have faith” but only have a knowledge of its content. Thus, “when we find a Christian” who only asks “if it is licit to do this and if the Church could do that,” it either means “that they do not have faith, or that it is too weak.”

Here, the pope seems to be calling out Christians who place their faith in the law rather than in Jesus Christ himself. They assume that following (their interpretation of) the law is sufficient to respond to all difficult situations, rather than relying on trust in God’s mercy and a tender, creative response to human suffering. One of the cases he cites, for example, is the leaders who asked whether “a woman was widowed, poor thing, who according to the law had to marry the seven brothers of her husband in order to have a child.” Casuistry, in this sense, focuses on the moral dilemma, rather than the child of God who is suffering within it. It does not interpret the law in light of the merciful intentions of the divine lawgiver.

Two years later, in 2016, Francis portrayed casuistical reasoning as a malevolent snare. In another morning meditation summarized by L’Osservatore Romano, he cites the

“doctors of the law, who were always approaching Jesus with bad intentions.” The Gospel clearly tells us that their intention was “to test him”: they were always ready to use the classic banana peel “to make Jesus slip,” thus taking away his “authority.” They “were separated from the people of God: they were a small group of enlightened theologians who believed that they had all knowledge and wisdom.” But, in “elaborating their theology, they fell into case law, and could not get out of the trap.”

In this talk, Pope Francis sees casuistry as a mark of unjustified moral and intellectual pride, a tool for some people to view themselves, in deluded fashion, as morally superior to others and therefore more beloved by God. In the pope’s view, knowledge is not in itself the problem. Using knowledge to build up oneself by making other people smaller, more vulnerable, or less significant is a problem because it violates the command to love our neighbors as Jesus loves us.

In a 2017 morning meditation, Pope Francis contrasts casuistry with love of truth.

Francis observed, “casuistry is hypocritical thinking: ‘you can, you cannot.’” A thought “that can then become more subtle, more evil: ‘Up to this point, I can. But from here to there, I cannot,’” which is the “deception of casuistry.” Instead, we must turn “from casuistry to truth.” And, “this is the truth,” the pope noted. “Jesus does not negotiate truth, ever: he says exactly what it is.”

From this perspective, casuistry is a self-serving effort to comply with the letter of the law while subverting its spirit and purpose. It is a childish and ineffective attempt to reconfigure the radical demands of the Gospel to fit conveniently within our preexisting plans. This sort of casuistry can happen with liturgical requirements as well as moral requirements. A good example would be someone who finally puts the donut down while getting in the car on the way to Mass, figuring, “Well, it’s a twenty-minute drive, ten minutes to park and walk, and a good thirty minutes in church before I will get communion—so I comply with the one-hour fasting rule. I’m in just under the line! A personal best!”

Most recently, Pope Francis told a global conference of moral theologians that casuistry is a cramped and backward-looking form of moral theology. More specifically, he judged that:

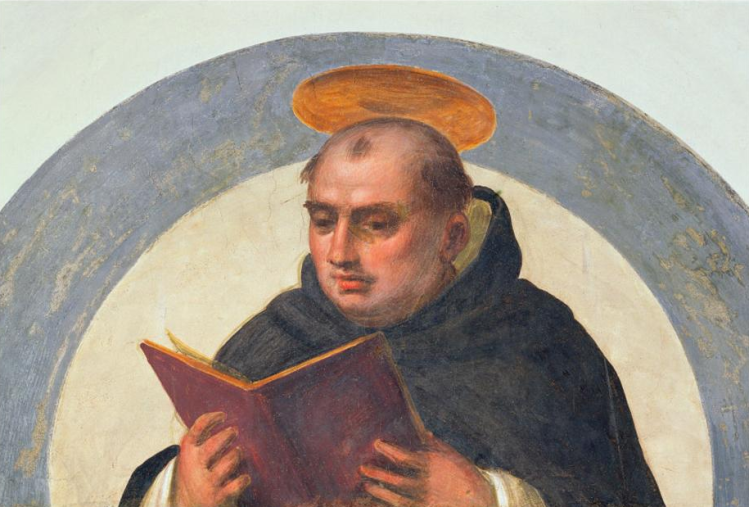

to reduce moral theology to casuistry is the sin of going back. The casuistry has been overcome. The casuistry was my food and that of my generation in the study of moral theology. But it is proper to decadent Thomism.

But what exactly does he propose to replace it? It is clear from the context that Pope Francis rightly believes that moral theology encompasses more than casuistry.

All of you are asked to rethink the categories of moral theology today, in their mutual bond: the relationship between grace and freedom, between conscience, good, virtues, norm and phrónesis, Aristotelian, Thomist prudentia and spiritual discernment, the relationship between nature and culture, between the plurality of languages and the uniqueness of agape.

Moreover, he urges Catholic moral theologians not to remain in their disciplinary ghettos; they must take into account the insights from other disciplines, including the sciences and social sciences. Moral theology is subject to development in at least two ways. First, it is always possible to grow in insight into the Lord’s requirements of us. Second, many of the particular judgments made by moralists depended tacitly on normative accounts of how things are that have since been called into question by science, social science, and human experience. For example, in contrast to St. Thomas’s view that women were in some sense “defective males,” we now recognize that they are fully morally and intellectually equal to men.

In addition, Pope Francis encourages moralists to take seriously the particular experience of the faithful, in order to recognize the Gospel enfleshed in human lives, rather than treating it as an abstract ideal. “Theology has a critical function of understanding the faith, but its reflection starts from living experience and from the sensus fidei fidelium.” Good moralists do not separate themselves from the lives of ordinary Catholics, but engage those lives with compassion and insight.

Most importantly, Pope Francis emphasizes the need to pay attention to people’s good-faith efforts to do the best they can, facing pain, brokenness, and limitations. The task of the moralist is not to pile burden upon burden, but to open space for grace for the faithful, “who often respond as best as possible to the Gospel in the midst of their limits and carry out their personal discernment in the face of situations in which all normative schemas are broken.” What does that mean, concretely? Traditional casuists often considered one action at a time: Is such-and-such activity a sin or not? If it is, that’s the end of the story—don’t do it. But as Aquinas recognized, sometimes people (often, if not always, through their own prior choices) find themselves in situations where there is no perfectly morally acceptable path forward for them. Catholic moralists cannot simply say, “Too bad for you.” They need to help people in these situations bring their lives into accord with God’s will for them, step by step.

In my view, Pope Francis’s criticisms of the dangers of casuistry are on point. In fact, the first definition of “casuistry” in some dictionaries concurs with his negative judgment on the practice: It is “the use of clever but unsound reasoning, especially in relation to moral questions; sophistry.” (Another pejorative synonym for casuistry is “Jesuitical” reasoning.)

But at its best, casuistry doesn’t have to be sophistry. Nor does it have to be the rigid and unyielding application of abstract rules to facts, like a TurboTax program for moral problems. In fact, good casuistry very much resembles the kind of moral theology the pope is calling for. Good casuistry is not mechanical, deductive reasoning solely focused on avoiding sin. It calls for the rules and the facts to be in dialogue with each other, press upon each other, and reshape each other.

Let us begin with human experience. At its core, casuistry is the practice of discernment about what to do in particular situations. It is not the practice of an armchair intellectual. Doing it correctly requires both prudential judgment, love of others, and a fair amount of self-knowledge. It is an everyday practice, not one reserved for priests hearing confessions. Say, for example, you have to decide whether to go visit a sick grandparent or prepare for an important meeting. You examine your motives—if you skip the visit, are you overly ambitious or merely fulfilling responsibilities to your coworkers? If you make the visit, are you honoring your elders in their frailty, or merely shirking an unpleasant work task? You look at circumstances—for example, you might ask whether one of your cousins is making a visit to your grandmother this weekend, or whether she will be alone. And very frequently, we ask for advice from wise people who know us well.

Whereas academic casuistry spends a lot of time focusing on intrinsically evil acts, in real life, if all goes well, acts that we think are intrinsically evil don’t even come up as an option in our deliberations. For example, murder is an intrinsically evil act and therefore always wrong. When deliberating how to balance their obligations to their grandmother with their work obligations, most people (thankfully) don’t say, “Well, I could kill my boss, and then the assignment would be postponed so I could go see Grandma. What do you think of that idea, Mom?”

The problem, of course, is that many Catholics don’t think that certain acts that Church teaching has considered intrinsically evil are in fact rightly described in that way. Many people don’t think contraceptive acts or homosexual acts are always wrong, but believe that their moral status depends on broader circumstances. While Pope Francis has not endorsed these positions, he has also not shut down discussion, or driven theologians or laypeople who hold those views out of the Church. He knows, for better or worse, the adage “Roma locuta est, causa finita est” (“Rome has spoken, the matter is settled”) is not descriptively true anymore, if it ever was. So the pope is willing to talk.

We all engage in casuistry. As moral agents, our decision-making is about the particular moral choices we face on a daily basis. At its best, the casuistry of moral theologians supported rather than supplanted the casuistry of ordinary life. Consider, for example, the rule of double-effect, a mainstay of Catholic casuistical reasoning. It states that we are responsible for the effects that we purposely bring about in a different way than those that we merely foresee will occur as a result of our action. There is an enormous debate about how to apply the rule in difficult cases, but it makes intuitive sense at its core. We all know, for example, there is a difference between taking Tylenol with codeine with the purpose of getting high, on the one hand, and taking it in order to quell a bad cough, foreseeing but not intending that your mind will be thoroughly addled by the medicine, on the other. Let’s stipulate that it is always wrong to get high on purpose—so the first scenario is not a morally acceptable option. Under certain circumstances, however, it is morally permissible to get high as a side effect of taking medicine, such as when you are safely tucked in your bed at home. But under other circumstances, knowingly causing the side effect of getting high, even if it’s not part of your purpose, is morally irresponsible.

Despite their limitations, traditional moralists addressed many issues faced by Catholics in ordinary life. They had to, if they were to help parish priests distinguish sinful from non-sinful actions. For example, they addressed one type of situation under the ominous label “cooperation with evil.” The question raised by the label is how far and in what respect one agent can contribute to the sinful actions of another agent without falling into sin herself. If my job is to maintain the heating system at a munitions plant that manufactures counter-population weapons, I am contributing, in at least some small way, to the making of such weapons by the company. Is my “cooperation” with their evil activity permissible, or do I have to quit my job? Does the fact that I have five kids to support affect the analysis? Would it make a difference if counter-population weapons were only a small part of their product range?

Agents who live in the real world face cooperation with evil questions all the time. Do you drive your alcoholic uncle to the liquor store so he won’t drive himself? Do you look the other way when one of your friends cheats on a test? Do you type and mail the fraudulent letter your boss is sending to the firm’s clients? These are not easy questions to answer. They require discernment, prudence, and attention to the facts. For many people, they also require consultation with others they consider morally wise. Good casuistry, in other words, must be integrated with an account of prudence and the other virtues.

Is academic casuistry as a part of Catholic moral theology worth saving? I believe it is. But we need to ask: Can academic casuistry be reformed to reflect the place of the practice in ordinary life? Could it redeem its bad reputation in the eyes of Pope Francis? I believe it can, provided that it is oriented toward the imperative of “accompaniment” that has characterized his moral teaching. Academic casuistry can no longer attempt to replace the consciences of the Catholic faithful. It needs to function primarily as a companion and a guide, rather than merely as a judge.

What would a reformed casuistry of accompaniment look like? In his recent talk to moral theologians, Pope Francis stated that “the true Thomism is that of Amoris laetitia,” which presents “the living doctrine of St. Thomas” because it “keeps us going, taking risks, but in obedience.” Rereading Amoris laetitia, I see four elements that a renewed Thomistic casuistry would need to emphasize.

First, St. Thomas said that the acts appropriate for casuistic analysis are the acts of human beings (excluding merely mechanical acts like stroking one’s beard). The manuals of moral theology tended to consider human acts in very abstract and schematic forms. By abstract, I mean that they don’t actually invite the confessor to consider the act as something done by a particular person, for a particular reason, subject to particular pressures, at a particular time and place. They ask the confessor to fit the act into precut categories of Aristotelian moral philosophy, which looks at the object of the act (its immediate purpose), its end (its larger motive), and its circumstances.

These are very useful categories for analyzing an act. But they are not self-applying. And if they remain at the abstract level, they are not likely to capture all the relevant features of the acting agents. So a reformed casuistry needs to pay as much attention to the acting person as to the act itself, and to situate that act within the broad life course of its doer. In Amoris laetitia, Pope Francis reminds us that the people who are acting are thoroughly embedded in families, societies, and the responsibilities and limitations they have accumulated over time. They have goals they have set, goals they have abandoned, and goals they don’t even articulate to themselves. They are subject to bad luck, social pressures, and internal and external limitations. Often, the circumstances of an action are not “mere circumstances.” They are part and parcel of the life and identity of a socially embedded human person.

Second, Pope Francis often emphasizes that “time is greater than space.” Whereas the classic manuals of casuistry analyzed sins, they did so by abstracting the act in question from the broader context of the penitent’s journey of faith. By emphasizing time, as well as God’s loving accompaniment of each of us through time, Pope Francis is asking casuists to consider where and how an act fits in a particular person’s life. It may be impossible for the person to break all bad habits at once, particularly addictive ones like sex, drugs, and alcohol. Small steps might be necessary. Pastoral theology has always considered such issues, of course. What Francis is saying is that good academic moralists need to do the same thing.

This is where Francis runs into controversy with his more conservative critics. Francis accepts, in my view, the Church’s teaching against all sex outside heterosexual marriage. In his terms, he would say it is an “ideal.” By that he does not mean that it is not true or binding—although that is how some conservative Catholics interpret him. He means that it is very difficult for everyone to get from a disorganized and morally disintegrated situation to one that is organized and morally integrated. No one will ever get there all the way. Some people might get closer than others. But moralists have to be able to say something more than “Don’t have sex. It is a mortal sin. You will go to hell.” Their job is to help people discern a concrete and specific and workable path forward.

Third, and relatedly, Pope Francis asks moralists to recognize the interplay between circumstances and rules. It is not always possible to take an abstract rule and apply it mechanically to particular situations; sometimes, particularities generate their own exceptions in ways that cannot be fully anticipated by any moralist. Francis quotes Thomas Aquinas, who observes that “although there is necessity in the general principles, the more we descend to matters of detail, the more frequently we encounter defects.”

Fourth and most importantly, an approach to casuistry inspired by Pope Francis would emphasize that the moral law has to be interpreted according to the intention of the lawgiver—Jesus Christ. In the end, moral theology is dependent upon Christology for its fundamental orientation. Pope Francis writes:

[The Church] turns with love to those who participate in her life in an incomplete manner, recognizing that the grace of God works also in their lives by giving them the courage to do good, to care for one another in love and to be of service to the community in which they live and work.

This, in my view, is the most groundbreaking aspect of Pope Francis’s approach to moral theology. It is also a point on which he breaks with Aquinas, at least as he is commonly interpreted. For Aquinas, and most of the casuists who followed him, a person who has committed a mortal sin has cut herself off from God’s love and grace, which can only be restored with confession and repentance. In Pope Francis’s view, God does not abandon us, even when we try to abandon him. God works with us patiently, gently, trying to turn us around without breaking us. The task of a Catholic moralist, and the challenge to a casuistry renewed in light of Pope Francis’s teaching, is to be faithful to this understanding of a God who does not give up on anyone.