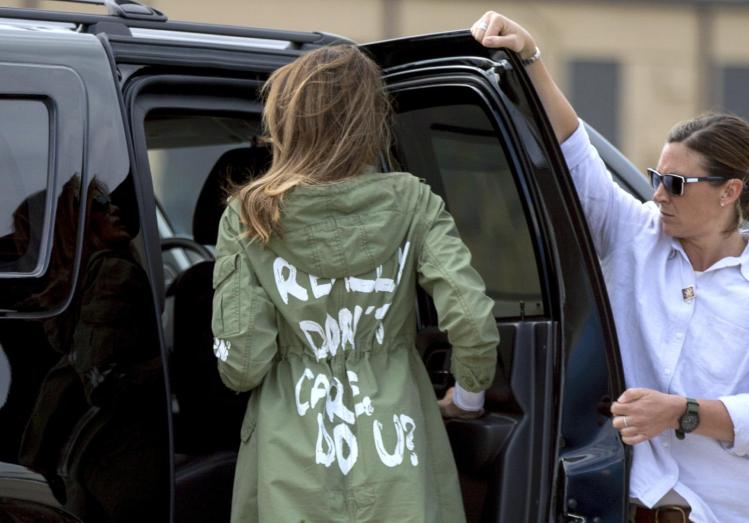

“I really don’t care. Do you?” These words were emblazoned on a jacket that Melania Trump infamously wore to visit a Texas refugee center during her first stint as First Lady. I was reminded of that jacket over the holidays, when I reacquainted myself with F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, a stinging indictment of runaway capitalism in the last century’s Roaring Twenties. I re-read the novel because I thought it might prepare me for the roaring twenties we confront today.

In the voice of his narrator Nick Carraway, Fitzgerald writes of two main characters: “They were careless people, Tom and Daisy—they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.”

But what does it mean to be careless? And conversely, what does it mean to care? The answer isn’t as simple as you might think. The challenge comes from the interplay of reason and emotion in our conception of caring.

In the law, the “duty to care” is a matter of reason, not emotion. We all have an obligation to exercise “reasonable prudence” in our relations with other people. Otherwise, we are guilty of negligence. The concatenation of negligent acts in the second half of The Great Gatsby could fill an entire torts class in law school: After confronting Jay Gatsby about his affair with his wife, Daisy, Tom Buchanan allows Jay to drive Daisy back to Long Island. Jay then permits the feckless Daisy to drive as a way of calming her nerves. Daisy drives too fast through the Valley of Ashes, where she inadvertently runs down Tom’s mistress, Myrtle, who had thoughtlessly run into the busy road to escape her own angry and irrational husband, who had imprisoned her to thwart her infidelity. Rather than stopping to address the damage they caused to life and property, Daisy and Jay simply speed on home.

Fulfilling the legal “duty to care” does not require us to have warm feelings for everyone we encounter. It does demand us to think about the likely consequences of our actions, and to adjust our plans so that they do not involve unreasonable risks to other people. The presupposition of the legal duty is intellectual, not emotional: other people’s lives are as important to them as ours are to us.

But what about the emotional component of caring? The Great Gatsby suggests that this component can be distortive and dangerous, even lethal, because it is ultimately egocentric. Gatsby certainly cared about Daisy—enough to recreate himself and his world for her. Yet the Daisy he cared about was a perfect illusion, not a flesh-and-blood woman. Ultimately, he desired to possess her as a symbol of his own perfect triumph, his own perfect acceptance by the moneyed establishment. Tom cared about his mistress Myrtle—he told Nick that he cried like a baby after her death. But his grief is about his own loss of companionship, not her loss of life. And even Nick, the narrator, falls prey to his own form of egocentric caring. While condemning Tom and Daisy for their careless harm-doing, their biggest offense in his eyes is refusing to attend the “great” Gatsby’s funeral. Nick cared about Gatsby. But why? Why exactly was Gatsby great in Nick’s eyes? Ultimately, because of his single-minded care for Daisy. Although he positions himself as an objective observer, Nick’s fundamental loyalty is to the least objective character in the novel.

Not all emotional caring is egocentric, of course. In the 1980s, the ethicist and psychologist Carol Gilligan developed an “ethics of care” as a supplement and corrective to the ethic of justice proposed by her mentor, Lawrence Kohlberg. She contended that men and women frequently used different moral vocabularies. While men focused on objective standards and impartiality, women tended to emphasize flexible responses to the perceived needs of particular individuals. Gilligan and other feminist ethicists criticized a purely objective account as susceptible to a cold indifference to the plight of actual people, and lifted up women’s practice of affective engagement with others as a more helpful account of the moral life.

But Gilligan’s theory was also criticized, by both men and women, on a number of grounds. Some scholars objected that it viewed responses to complex ethical problems through the lens of gender essentialism. Others noted that caring individuals can and do cause harm. They can base their caring on a false view of what is good for the other. More problematically, they can fail to see that (within limits) other adults are entitled to define their own well-being, something that a pure care ethic may not fully account for, since it seems to be based on the relationship of mothers and children.

Is there a way to sort through all of these complications? I think Margaret Farley’s idea of compassionate respect provides a way forward, in two important respects. First, the word “compassion” is much more helpful than “care.” Compassion requires us to “feel with” a suffering human being, rather than to use them as an occasion to focus on our own feelings. Second, respect anchors our feelings of compassion in a deliberate commitment to the well-being of the other as a person who is equal to but distinct from us. It encourages us to attend to their objective needs (e.g., food and shelter), as well as their subjective needs. And it deters us from uncritically projecting our beliefs, desires, and needs onto them.

Farley’s concept of “compassionate respect” allows us to validate the reason-based “duty to care” operating in the law, while also critiquing the egocentric examples of caring we find in The Great Gatsby. It also helps to understand why so many of us were unnerved by Melania Trump’s jacket. We could not help but wonder: Was she so insulated by her own wealth and proximity to power that she no longer could “feel with” hungry, thirsty, and fearful human beings? Was the gulf between her world and the world of the refugees so great that she even had trouble viewing them as human beings with equal dignity?

In the world of The Great Gatsby, the Valley of Ashes, a desolate, dry place inhabited by the souls left behind by uncontrolled capitalism, lays halfway between the skyscrapers of Manhattan and the mansions of Long Island. In our world, the Valley of Ashes can be found at our nation’s southern border.