The perception of Roman Catholicism as unswervingly resistant to the innovations of modernity between the Council of Trent and the Second Vatican Council needs correcting, Ulrich L. Lehner argues, by remembering persons and impulses through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that represented openness to those same initiatives. It is a bold move to call the scattered evidence he gathers “the Catholic Enlightenment,” although not so bold as Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger’s claim that the Enlightenment was a thoroughly Christian invention! The title must appear especially oxymoronic to those comfortable with the binary opposition between classic Enlightenment figures like Spinoza, Voltaire, and Hume, and Tridentine Catholicism, an opposition expressed most vividly by Voltaire’s call to “destroy the infamous thing!”

Lehner does not propose that “Catholic Enlighteners” primarily accepted or drew from the philosophical premises of Christianity’s cultured critics (although some did), but that for the most part they continued the reforms of Trent and the intellectual spirit of Renaissance humanism as the basis for integrating modern science and philosophy into a religious worldview. Instead of defining religion “within the bounds of reason alone” (Kant), they built on the older tradition of “faith seeking understanding” (Anselm), but their faith was unusually open to new forms of understanding. Just how diverse in form and substance this “global movement” was is illustrated by Lehner’s first chapter, “Catholic Enlighteners Around the Globe,” which rapidly surveys an array of responses to intellectual, moral, and political issues that were current in France, Portugal, Spain, and Italy: epistemology, marriage and celibacy, historical criticism of the Bible, reform in the church, the role of the state, all these were vigorously engaged by Catholic thinkers.

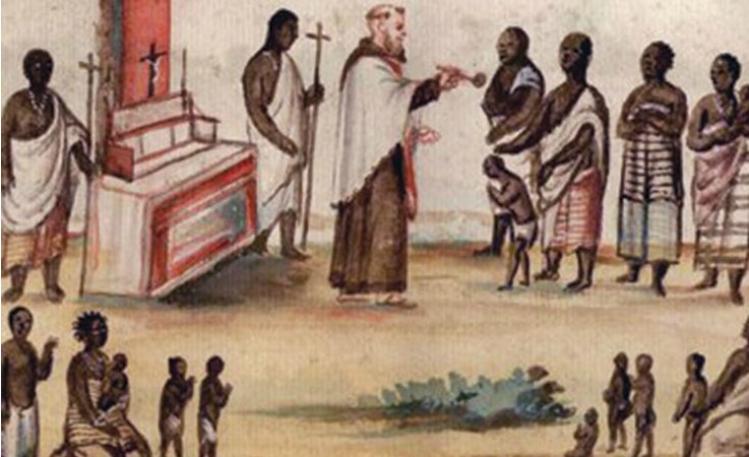

Fortunately for the reader who might be a bit overwhelmed by this wide-ranging and crowded catalogue, Lehner’s subsequent chapters provide a more detailed examination of a number of specific issues that are, not accidently, also pertinent to discussions about reform in the contemporary church. He takes up in turn the topics of toleration and tolerance; of intellectually active and morally powerful women; of adaptation to the local cultures of China, India, and the Americas; of resistance to superstition in favor of a more rational faith; of saints defined more in terms of moral witness than of wonderworking; of attitudes and practices regarding slavery and the assessment of the humanity of slaves. Each discussion brings to light figures who have been little noticed or celebrated, and initiatives that were markedly in advance of their time.

In examining these issues, Lehner does not romanticize. He is candid about the ways in which enlighteners fell short or failed, and especially about the ways the papacy in particular was an erratic and mostly resistant player (see especially Benedict XIV). But he also points out those areas in which Catholics were more “enlightened” and more consistent in their actions than were the official heroes of the Enlightenment. Lehner connects the collapse of this remarkably open and progressive form of Catholicism in the early eighteenth century to two factors, which combined and came to a climax in the French Revolution: the way in which reform was often aligned to the power of secular states, and the way in which the political fortunes of the papacy were correspondingly threatened. After the explicit suppression of the church in revolutionary France, a newly invigorated and militant papacy defined authentic Catholicity after 1789 in direct opposition to the forces of modernity: if there was to be reform it was to be on the basis of Trent alone.

This impressively learned study rewards—and demands—careful reading. It opens up the possibility for further research into neglected aspects of Catholic history, and provides lessons (positive and negative) for those considering how the church today might respond more productively to the intellectual and moral challenges of the present era.