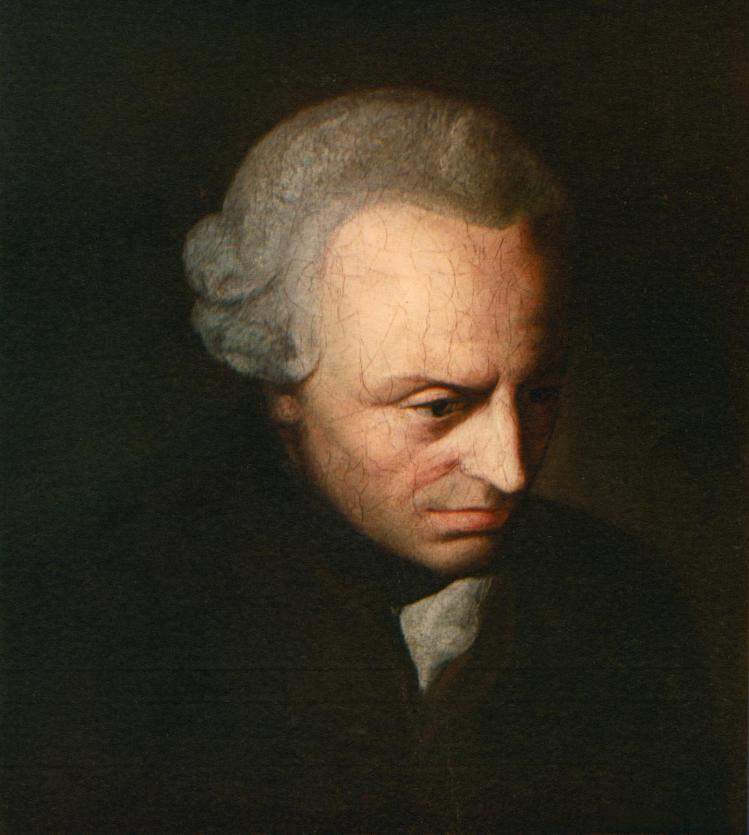

On June 11, 1827, the Catholic Church placed German philosopher Immanuel Kant’s (1724–1804) most famous work, the Critique of Pure Reason (1781), on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum. A report from the Index Congregation that day, given to the pope to make a final decision, simply states: “Kant’s dark, sophistical, and incomprehensible philosophy is already well known, as is his irreligion. It would be too tedious to give even a brief idea of this work here, which is actually suitable for nothing other than sowing doubt and confusion regarding every kind of truth.”

By the time the First Critique (so called because it was followed by two others) was banned its author was long dead, and he had not even been Catholic to begin with. Yet Kant’s work was considered such a threat to Church teachings that even scholars needed special permission from their bishop or religious superior to consult it. But many clerics didn’t even feel the need to read Kant to attack him. Jesuit Guido Mattiussi, a central figure in the Neo-Thomist movement and the controversies over modernism, reportedly boasted of writing his 1907 book The Kantian Poison without ever having read Kant himself.

The Church’s response to Kant, which I had the opportunity to research in the Vatican archives, serves as a stark reminder of a dark chapter in the history of faith and reason, but it also shows the Church’s ability to overcome some of its historic errors. The episode is particularly pertinent in 2024, which marks Kant’s tricentenary. Today, critical thinking and academic freedom are once again under attack. Even in the United States, the “land of the free,” school boards and state politicians have resorted to book bans to protect certain political or moral views. But promoting non-thinking over critical engagement with uncomfortable ideas is never fitting for Christians, who are called to be fearless witnesses to the truth (John 8:32).

The Index proceedings in 1827 were marked by superficiality, philosophical misunderstanding, and theological bias. The censor, Camaldolese abbot Alberto Bellenghi, could not read German and only had access to a flawed 1820 Italian translation. He relied on secondary sources that misunderstood and distorted Kant’s philosophy, particularly an influential 1803 Italian introduction to Kant by Francesco Soave. Although Soave’s book promises a “thorough analysis” of Kant’s philosophy, he quickly reveals his true intent: to propose a blanket rejection that “a philosophy like Kant’s” deserves. Kant, Soave writes, “aims at destroying all ideas and all knowledge that have been so firmly established in both the practical and the speculative sciences.”

What made Kant so suspicious was his “critical” project: he rejected dogmatic philosophies that never questioned their basic assumptions, proposing instead a critique of the capacities of human reason. Kant revolutionized epistemology by suggesting that “concepts don’t conform to objects, but objects to concepts.” Recognizing that human knowledge is constructed through what he termed “transcendental” categories of the mind, Kant’s philosophy holds that we cannot know “things as they are,” but merely as they appear to us.

This seemed to open the door to anthropocentrism, subjectivism, and, worst of all, relativism—the denial of absolute truths. Kant’s Catholic critics defended epistemological realism, asserting that what is knowable exists in the object independently of the person perceiving it. They took particular issue with the fact that Kant limited certainty to the realm of experience, denying the ability of traditional metaphysics to produce secure knowledge of non-empirical matters. Soave invokes Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas, and modern thinkers like John Locke to uphold realism and natural theology, concluding that “transcendental philosophy can have no place other than in the realm of dreams and chimeras.”

In his report, Abbot Bellenghi repeats Soave’s prejudices word for word and calls Kant’s philosophy a “mad” irreligion opposed to Church doctrine. He repeats Soave’s misunderstanding of Kant’s doctrine of categories, conflates the empirical and the transcendental realms, and mischaracterizes Kant’s account of judgment as a matter of mere subjective arbitrariness. He also cites a misbegotten example from Soave meant to reduce Kant’s philosophy to absurdity: “the sun” is “one” for Kant, he writes, while “the stars” are many, simply “because it pleases the mind to apply its category of unity to the sun and the category of plurality to the stars.”

Naturally, Bellenghi is particularly appalled by Kant’s critique of the traditional proofs of God’s existence, and he cites the fact that even in Germany Kant’s teachings had been met not only with agreement but also with disapproval and censorship. Kant’s “most important disciple,” he writes in reference to J. G. Fichte, was even “accused of atheism and removed from his professorial chair.”

Bellenghi couldn’t see that, in fact, Kant’s critical philosophy was partly motivated by a theological insight. Kant himself never questioned the existence of God—God, for him, was a “postulate of practical reason.” He sought not to disprove God’s existence but to point out the limits of human reasoning about the transcendent, denying our ability to “prove” God through logic and natural theology. In short, Kant claims he “had to deny knowledge in order to make room for faith,” echoing the Augustinian idea that, as Karl Jaspers put it, “a proven God is no God.”

The historical background to the 1827 condemnation is, in many respects, even more interesting than the condemnation itself, particularly the question of when and how anti-Kantianism first found its way into the Vatican. These earliest stages in the history of the relationship between the Church and Kant were shrouded in darkness when I set out to find clues in the Roman archives.

It was long believed that the cumbersome Roman censorship apparatus reacted late to Kant due to the language barrier and a late-arriving Italian translation. But it became clear in my research that Rome was aware of Kant’s philosophy and its influence on Catholic theology well before that. After finding nothing decisive in the archives of the Sacred Congregation of the Index or the Congregation of the Holy Office of the Inquisition, I ventured into the Vatican Secret Archive (renamed “Vatican Apostolic Archive” in 2019). The Secret Archive, despite its name, has welcomed scholars for over 130 years (“secret,” or secretum, refers in this context to the pope’s private archive as opposed to the archives of particular Church offices).

Not long after I started my research there, I made a discovery in the dusty boxes containing the diplomatic correspondence between the Vatican’s Secretariat of State and the papal nuncios in Vienna and Munich. Correspondence from the Viennese nuncios Luigi Ruffo-Scilla and Antonio G. Severoli includes several references to Kant—still alive at the time. They make every effort to portray Kant’s philosophy as a threat to the Christian faith. The oldest dispatch mentioning Kant, from Ruffo-Scilla, dates from September 5, 1801:

Kant’s philosophy has been proclaimed by him in Königsberg and then printed in German; the fuss, the fame, the admiration garnered by the large number of his students and followers have encouraged many others to explore the depth, if not to say the darkness, of his concepts, from which the worst principles and godless propositions emerge.... When I read today the work of the priest Pietro Miotti, it confirms my opinion that the new philosophical system of Kant requires the attention of the Holy See to protect the faithful from so much poison against religion.

A few months later, following a request from Cardinal Secretary of State Ercole Consalvi, Ruffo sent what he calls some of Kant’s “poisonous” books.

Pietro Miotti’s name stands out in the correspondence between the nuncios and Rome. The author of two books, Miotti was an Italian-Austrian ex-Jesuit and philosophy teacher in Vienna who dedicated his entire energy to the fight against Kant and early Catholic Kantians. Miotti’s criticism is not very original, but he does offer earnest zeal and polemical pungency. Miotti’s judgment about Kant is unequivocal: his philosophy is not only incomprehensible but also irrational; it is “materialism, skepticism, idealism, false philosophy, sophism, irreligion” and must be opposed with “true, rational philosophy.”

Miotti requested that the papal nuncio send his writings and a personal letter to Pope Pius VII, and he provided Rome with a template for action against Kant. The vocabulary used in later Church documents seems to come straight from Miotti and his sources, like theologian Benedikt Stattler, who coined the phrase “Kant’s poison” in his bluntly titled book Anti-Kant. Although the Index Congregation didn’t start an investigation then, it is remarkable that Ruffo and Consalvi use a quasi-juridical term as an honorary title and nom de guerre for Miotti: they call him “impugnatore” (challenger in court) of Kant, viewing him as a prosecutor on behalf of the Church.

Miotti does not engage with the critical concerns of Kant’s philosophy, but he does at least try to base faith on some intellectual foundation. He shares the Scholastic belief that faith and reason are inseparably one: the faithful have reason on their side; what is irreligious is unreasonable; and what is unreasonable is irreligious. This, he thinks, is especially true for Kant’s denial of a healthy realism, which, in Miotti’s view, is the empirical basis of traditional metaphysics and Christian doctrine. It is, he writes, of utmost importance to “break a culpable silence against Kantian philosophy in order to uphold reason and religion.”

The intellectual resources of Miotti and his sources ensured that the Vatican’s opposition to Kant wouldn’t appear an amateurish and superficial appeal to blind faith. He offered a philosophical bulwark in which Aristotle, Aquinas, and others became part of the official Catholic policy for dealing with Kant’s critical philosophy. Some decades later, Leo XIII’s encyclical Aeterni Patris (1879) prescribes an official antidote to Kant and all modern philosophy: Neo-Thomism.

The nuncio in Munich was also aware of the controversy. Archbishop Annibale Sermattei della Genga (1760–1829) was a reactionary deeply skeptical of the achievements of the Enlightenment and among the first Vatican officials to warn against Kant in 1801. Della Genga would later become Pope Leo XII and oversee the 1827 Index proceedings.

Della Genga’s correspondence with Rome as de factio nuncio in Bavaria from 1801 to 1808 reflects his concerns about the spread of liberal thinking and his hope for religious renewal. Della Genga complains in particular about the “godlessness” at Bavarian universities. He explicitly mentions the University of Würzburg, where the early Catholic Kantians Maternus Reuß and Andreas Metz taught, takes offense at the Benedictines of Salzburg who embrace Enlightenment thought, and views the Bavarian state university—recently relocated from Ingolstadt to Landshut—as a “cloaca of corruption” due to the influence of Enlightenment philosophy.

Against such “French conditions,” he writes to Rome on March 18, 1800, one must “wage war.” Della Genga blames the Bavarian Elector (later Bavaria’s first King) Maximilian Joseph and his advisor Count Maximilian von Montgelas for introducing religious tolerance, freedom of the press, and secular education in a state that, for a long time, had been a stronghold of conservative Catholicism. Since Max Joseph and Montgelas also supported anti-clericalism and the secularization of Church property, they became, in della Genga’s view, not only intellectual and spiritual but also political opponents of Rome and the Catholic Church.

Like Miotti, della Genga was particularly concerned about Christian education. In a dispatch to Rome dated September 14, 1801—just about a week after Ruffo had first reported Kant to Vatican authorities—della Genga offers a sweeping critique of Bavaria’s educational reform and laments “the doctrine that is printed and taught in schools and elsewhere. The professors are extremely bad, and by the Elector’s command, the skeptic Kant is used as the book that must be followed as a model.”

Whether Kant was already used as a “textbook” at that time is unclear. But his works were certainly read at universities, and, in 1799, Max Joseph explicitly allowed the lyceums (secondary schools) of Amberg and Munich to read Kant’s writings in order “not to fetter the free search for truth and the rational activity of the citizens.” In 1808, the philosophy curriculum for public secondary schools recommends Kant’s critique of proofs of God’s existence for the units on cosmology and theology. And for ethics and legal philosophy, the curriculum states, “Kant’s writings are sufficient for the time being.” Della Genga would have taken grave offense: ethics students at public schools were reading the very philosopher he saw as a danger to Catholic morality.

Della Genga was elected pope in 1823 as a candidate of the reactionary “zelanti” faction, which was sharply opposed to modernity, secular influences, and the liberal ideas of the French Revolution. His pontificate was a phase of both renewal and conservative restoration: the optimization of Vatican bureaucracy and the administration of the Papal States went hand in hand with strict measures of control. Harsh police actions led to Leo XII’s widely documented unpopularity. And while he promoted the sciences and education (for example, by creating the Congregatio studiorum, which oversaw the Vatican’s educational institutions), his efforts aimed not only at quality management but also doctrinal orthodoxy. Instead of seeking dialogue with modernity and its philosophical currents, the Church walled itself off.

It is uncertain whether the pope himself initiated the proceedings against the First Critique. Interestingly, the available records from 1827 make no mention of a formal complaint, which was usually required for the Index Congregation to investigate suspicious writings. Still, Kant’s allegedly “sophistical and irreligious philosophy” was indeed “well known” to Leo, as the Congregation’s June 11, 1827, report put it. And, whether or not he was involved from the beginning, his pontificate certainly prepared the ground for the official condemnation.

A fearful church couldn’t diminish Kant’s enormous influence on the history of modern thought. Time has rendered its judgment: Soave, Bellenghi, and Miotti are forgotten, while Kant is more relevant than ever. Just twenty years after the 200th anniversary of his death, the world celebrates another Kant year with numerous events all across the globe to commemorate the 300th birthday of one of the most important philosophers of all time.

But the Catholic Church, too, has been able to adapt. Although it still has reservations about the Zeitgeist, often raising critical concerns, the Church is now willing to look for Zeitzeichen (“signs of the times,” see Gaudium et spes 4), recognizing them as expressions of the sensus fidelium and thus as potential “sources of theological knowledge” (the German bishops in a document for the 2023 Synod on Synodality). Indeed, Pope Francis has rekindled the Vatican II spirit of aggiornamento.

As far as the Church’s current attitude towards Kant is concerned, I will only mention a personal letter Pope Benedict XVI wrote years ago to Norbert Fischer of the Catholic University of Eichstätt and an international group of scholars, including myself, that Fischer had convened to produce a comprehensive account of the Catholic reception of Kant. In his letter, Benedict, often seen as anti-progressive himself, emphasized the importance of Kant for Catholics and commended us for our 2005 book Kant und der Katholizismus.

Not only has the Church put the Index of Forbidden Books behind it (it was abolished in 1966), but one can also hope that it continues to be open to critical self-reflection and fearless dialogue with modernity, using faith and reason as the “two wings” on which the one, God-given “human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth,” as the 1998 encyclical Fides et ratio so aptly puts it. However critical it may be, no philosophy that strives for truth is poison to faith.