It’s no exaggeration to say that Americans’ faith in institutions is at a nadir. A June 2023 Gallup survey found that public confidence in everything from the presidency to the medical system to newspapers is at or approaching record lows. Trust in religious institutions is also plummeting, a fact underscored by runaway rates of disaffiliation. As recently as 2007, 78 percent of Americans identified as Christian, while only 16 percent described themselves as religiously unaffiliated. Since then, self-identifying Christians have dropped to just 63 percent of the population, while “the nones” have risen to 29 percent. Some experts anticipate that the religiously unaffiliated could constitute a majority as soon as 2070.

The reverberations of this trend are visible across the country, including at the Mainline Presbyterian seminary where I teach. The percentage of nondenominational and unaffiliated students in our student body is growing, while the overall applicant pool for the Master of Divinity is shrinking. Many of those who matriculate are uncertain about whether they want to be ministers or work for a religious institution at all.

What they do know for sure is that they want the world to look different than it does now. Their righteous indignation about current affairs (the Israel-Gaza war being the most recent and pressing example) and the churches’ complicity in injustice can be a powerful force on campus and beyond. Their longing for honest reckoning and concrete change tends to nurture dissatisfaction with institutional half-measures, not to mention suspicion of those in power. Idealism and cynicism can be two sides of the same coin: if an institution can’t be today what it should have been yesterday, then perhaps it’s not worth fighting for in the first place. Social movements, activist networks, protests, and direct action have an electrifying appeal. Institutions seem destined to disappoint.

While it can be tempting to assume that today’s dissatisfaction is unprecedented, there’s a close analogue in American history: the Gilded Age. Janine Giordano Drake’s provocative book The Gospel of Church: How Mainline Protestants Vilified Christian Socialism and Fractured the Labor Movement underscores how the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries also saw soaring mistrust in institutions, especially the leading Protestant churches. For the small set of elite white Protestants that funded and frequented them, the picturesque church buildings that decorated the stark urban landscape of the industrializing United States evoked the beauty of “Christian civilization.” But those on the underside of the nation’s economic transformation viewed these same structures as a testament to the corruption of institutional Christianity.

The gospel of wealth propounded in the pulpit drove poor and working-class people out of the pews. As Drake points out, there were “nones” around the turn of the twentieth century, too: “The largest category of Americans in the 1906 census were, as was true a decade earlier, those with no religious affiliation.” But hers is not a secularization story. Even as working-class believers decried what they called “churchianity,” they retained a deep faith in Jesus of Nazareth, “a carpenter and refugee” who “afflicted the rich and comfortable with the gospel of social equality.” This faith coursed through the radical labor movement and, “in the absence of any common socialist nationality or culture,” held the Gilded Age community of socialists together.

That community cast a much longer shadow than most today would assume. At the turn of the twentieth century, capitalism’s endurance could not be taken for granted. Throughout that period, which was shaped by unchecked corporate prerogatives and state-backed violence against fledgling labor movements, radical critiques of the industrial order found a wide hearing. Drake illustrates their geographical reach with a series of maps documenting how socialist parties and the socialist press flourished across the country. Radicalism was rising not only in New York and Chicago but also in places like Girard, Kansas; Hendricks, West Virginia; Gulfport, Florida; and Burlington, Washington.

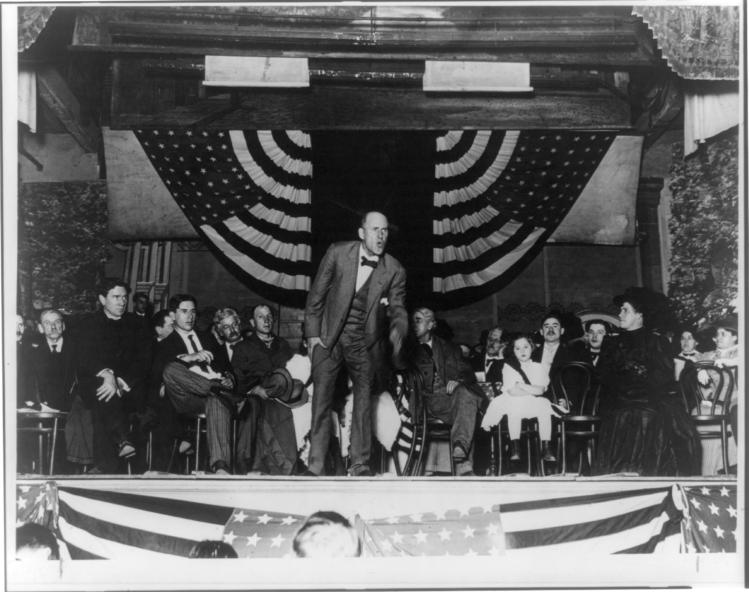

Beyond showing how Christian faith infused and animated radical movements, Drake also convincingly contends that Christian socialism belongs at the very center of the era’s political and religious history. Her cast of characters includes a few stars, especially Eugene V. Debs, who ran for president on the socialist ticket five times and won six percent of the popular vote in 1912. Debs “offered a new vision of Christian citizenship that valorized the poor and politically marginalized, including women and people of color, and endeavored to build a welfare state on the model of a community church.” While Drake acknowledges that racism and patriarchy were rife in wider radical circles, she finds in figures like Debs evidence that socialism was, on the whole, an egalitarian force.

Debs was anything but a lone voice crying in the wilderness. Drake describes how grassroots radicals championed municipal socialism in small towns and big cities alike, as their counterparts in the labor movement pushed the stolidly conservative American Federation of Labor (AFL) to the left. She also draws attention to a network of socialist-sympathizing ministers, which included well-known Christian social reformers like Charles Sheldon and Walter Rauschenbusch, as well as little-known figures like the Black Baptist George Washington Woodbey, the pioneering Unitarian Mila Tupper Maynard, and radical Catholic priests Thomas McGrady and Thomas J. Hagerty. By 1908, the Christian Socialist Fellowship boasted some twenty-five chapters, three hundred ministers, and five thousand subscribers to its flagship paper.

For socialists, it was a heady moment. “By 1908,” Drake writes, “socialism was threatening worldwide Christianity as the dominant expression of justice and morality.” More than a century on, one cannot help but wonder: How and why did this surging radical Gospel fade into relative obscurity? And how did conservative Christianity, which was back on its heels in the Gilded Age United States, come roaring back into the center of national life?

Drake places the blame squarely on Protestant institutions—and on one in particular. When thirty-three denominations came together in 1908 to found the Federal Council of Churches (FCC), they declared their joint ambition “to manifest the essential oneness of the Christian Churches of America in Jesus Christ as their Divine Lord and Saviour, and to promote the spirit of fellowship, service and cooperation among them.” At that gathering, the FCC adopted the “Social Creed of the Churches,” which drafted official positions on a variety of industrial questions. The FCC declared itself in favor of “the abolition of child-labor,” the “suppression of the ‘Sweating System,’” and the establishment of “a living wage as a minimum in every industry.”

Historians have often interpreted the FCC as a vehicle for a moderate Social Gospel—not especially radical, but nevertheless in favor of a deeper engagement in the fight for a just society. Drake sees something much more sinister at work: a reactionary plot, born of the clergy’s simmering anxiety, to pull the United States back from the socialist brink. In establishing the FCC, Drake argues, “white Protestant ministers effectively formed a trust (a non-compete agreement) on Christian ideals in order to keep the labor movement from drawing on the Christian tradition with its political demands.” These ministers forged close relationships with the leaders of the AFL, and yet this “conservative alliance,” as Drake sees it, was never about advancing the cause of social justice. Rather, this partnership was “formed by a shared desire to preserve an older social order, a regime where aspirant-class white Protestant men in the North acted as foremen and supervisors over women, brown-skinned and racially ‘in-between’ people.”

The plot worked, Drake contends, because of how adroitly the FCC and its wolfish operatives cast themselves as sheep. Historians have often remembered Methodist reverend Harry F. Ward, the primary author of the Social Creed, as a social-gospeler-turned-radical. But in fact, Drake argues, “he never quite escaped the paternalistic evangelistic posture of his parents.” She goes on to highlight the limitations of the Creed, “often interpreted as more radical than it was,” and questions Ward’s underlying priorities, observing that “his records brim not with evidence of better union contracts or municipal services, but with testimonials of workers who were so touched by his talks on the labor movement that they decided to join a church.”

The Presbyterian reverend Charles Stelzle serves as another case in point. An influential figure within the early FCC, Stelzle made a name for himself as a champion of workers. He joined the AFL and partnered with its leadership to galvanize the Men and Religion Forward Movement, an evangelistic campaign that proceeded on a purportedly pro-labor basis. But Drake chastises Stelzle, whom she regards as “fundamentally jealous” of socialist success, for always holding radicals at arm’s length. Stelzle and his FCC colleagues “said that they stood with the AFL, but in fact these clerics only stood with the most conservative members of the nation’s most conservative unions.”

Stelzle founded a Labor Temple in New York City that evolved in the 1910s into a major organizing hub for workers and socialists. Yet in Drake’s view, the fact that he refused to relinquish oversight of the space is more telling. During the World War I–era Red Scare, as scrutiny of the Temple’s activities intensified, its Presbyterian stewards failed to “defend the legitimacy of Christian Socialism as a Christian movement for positive social change.” True to form, they “refused to stand in alliance with the radicals.”

The saga of Stelzle’s Labor Temple is paradigmatic, in Drake’s analysis, of the FCC’s general insistence that all social-justice work operate through the Protestant churches. In so doing, the FCC quashed the independent moral authority of more radical voices. The dynamic grew worse after the end of World War I, when, according to Drake, “ministers were socializing with business leaders and President Woodrow Wilson in smoke-filled rooms” and taking cues for justice work from the likes of John D. Rockefeller.

Drake reads even Protestant ministers’ seemingly most worker-friendly messaging through a cynical lens. For example, in a report on a major 1919 steel strike, the clergy leading the Rockefeller-funded Interchurch World Movement called on their peers to take up a “legitimate prophetic role as advocate of justice.” Drake finds no earnest cry for reform in these words—only a call for the clergy to seize power and control. This suspicion of institutional Christianity—evident in Drake’s frequent use of flatly negative terms like “hoarded,” “extracted,” “exploited,” and “stole” to describe the FCC’s relationship with workers—pervades the entire book. The Protestant leaders promoting the Social Gospel “duped both the labor movement and the American people,” she concludes: “One might argue that these ministers were bribed by Rockefeller and other millionaires.”

Were the nation’s leading Protestants in fact so craven, their institutions so bereft of integrity? Drake is hardly alone in wanting to revise what she calls “the heroic narrative of Christian social service.” If an early generation of historians celebrated the rise of the Social Gospel as a historic breakthrough, more recent accounts have emphasized white Protestant reformers’ entanglement in the sins of racism, capitalism, and more. If Drake’s critique is even more bracing, it may be due to her keen sense of the stakes: had the constituencies that powered the FCC instead lined up behind the likes of Debs, as she believes their faith unequivocally demanded, then socialism (and, in her view, true Christianity) might have prevailed in the United States.

What does not come through in Drake’s story is that there were at least some within the FCC who were cheering for socialism, too. Many of the radical ministers Drake lionizes, including Rauschenbusch and Sheldon, were also involved in the FCC, which was a much bigger tent than Drake acknowledges. Its thirty-three member denominations encompassed everyone from Christian socialists Vida Dutton Scudder and W.D.P. Bliss to Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie; from Black civil-rights stalwarts Ida B. Wells, Reverdy C. Ransom, and Adam Clayton Powell Jr. to arch-segregationist white southerners. Power was not equally divided between these different constituencies, and Drake is right that elite white men kept a tight grip on the reins. But the FCC’s public witness was not easily determined by a single constituency. Behind the scenes there was always a scrum, with conservatives and moderates and progressives and, yes, sometimes even radicals championing their respective visions of the Gospel.

Participants in this scrum often made strategic calculations to advance an institutional long game. Rauschenbusch was a Christian socialist, but never became a card-carrying socialist party member. Among other things, he was afraid it would undermine his efforts to evangelize conservative churchgoers. He deemed it a worthy compromise, telling a former student, “Socialists in Rochester know that I am not a member of the party but they also know that I am making converts to Socialism right along and that my friendliness is helping them.” Harry Ward was similarly shrewd, collecting letters from labor leaders to gain leverage over the Right by showing how conservatives’ anti-labor stance was impeding their evangelism. For all his maneuvering, Ward still lost battles within both Methodism and the FCC. But even bruising defeats did little to deter him, as he wrote to the discouraged leader of the blacksmiths’ union: “You must not forget that the other crowd has been in control a long time, and we have been at this job only a little while.”

Ward’s faith in incremental institutional change was shared by other progressive clergy within the FCC, who hoped that their patient, persistent approach would transform the churches in a lasting way. Rev. Alva Taylor, one of the authors of the Interchurch World Movement strike report cited by Drake, regularly reminded his students at Vanderbilt Divinity School that there were downsides to giving up on the long, slow work of reforming institutions. “One can accomplish more fighting within than without,” he told them. “The very opposition one may incur will be educational to the group while if one is independent very few are concerned about what he does or believes.”

Of course, such counsel risks fostering complacency. Results matter, so what did the FCC actually achieve? Drake sees its main legacy as “the conservative Christian takeover of both the churches and the labor movement in the early twentieth century.” Yet some of the evidence she cites suggests a more nuanced picture. Prior to 1891, not a single Christian denomination endorsed organized labor in any form. Unbridled capitalism reigned supreme, with some Protestant ministers even endorsing the murder of unarmed foreign-born workers in the streets. Against this backdrop, the FCC’s promotion of a living wage, its affirmation of the legitimacy of trade unions, its advocacy for more humane immigration policies, and its insistence on a racially integrated membership—while less radical than the European socialism Drake extols—does not add up to a “conservative takeover.” The early twentieth-century FCC was compromising and incrementalist, but it pushed many conservative white believers in more egalitarian directions.

This interpretation also helps make sense of what happened after the 1920s, when the book’s main action ends. In her afterword, Drake brings the story up to the present day, making the case that an unbroken history of Protestant collusion with capital is responsible for America’s greatest collective ills, including Christian nationalism, white supremacy, and the rampant privatization of public goods. This bleak coda is too pat. Missing is any account of how the FCC threw its weight behind the New Deal, including many of its most radical dimensions. The organization’s support for the National Industrial Recovery Act, the Wagner Act, and more generated a significant backlash against ecumenical Protestant public witness, one that scholars have cited as an origin point for the contemporary Religious Right. Also missing from Drake’s account is any recognition of the fact that the FCC became, in 1946, the first large, predominantly white organization in the country to condemn Jim Crow. Its ecumenical successor, the National Council of Churches, lobbied alongside Black civil-rights organizations for the passage of landmark 1960s legislation. Ecumenical Protestants showed up in droves in support of Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta, and the United Farm Workers during that era, too.

While the grassroots certainly lit the spark of concerted action in the early twentieth century, a closer look at the historical evidence shows that institutional insiders—sometimes no less zealous for justice—also played key roles in achieving social change. Even when their victories were only incremental and provisional, they were still important improvements. Mid-twentieth-century America was better because institutionalists and activists took advantage of opportunities to pull in the same direction.

Whether they can do it again remains to be seen. Institutional work requires an openness to compromise. It is often slow and messy and always incomplete. At their best, institutions can be—and, in fact, have been—genuinely responsive to human needs. They are essential vehicles through which we sustain massive trans-generational projects, including, for example, both democracy and Christianity. When institutions lose their way or fail to stand for what is right, we need creative agitators to call out and challenge them. But we also need savvy insiders, committed to justice and to preserving the durable structures that will help secure it.

Every year, for reasons I can’t quite explain, as commencement rolls around, a significant percentage of the students who declared themselves nondenominational when they arrived have become Presbyterian, Episcopalian, or the like. Somehow, at some point, without abandoning their ideals, they seem to find value in institutional leadership and belonging. Our broken church and fractured world need these budding institutionalists and activists to work and build together.

The Gospel of Church

How Mainline Protestants Vilified Christian Socialism and Fractured the Labor Movement

Janine Giordano Drake

Oxford University Press

$34.95 | 328 pp.