Last summer, as I sat waiting for a train in Penn Station, I noticed a figure approaching and trying to get my attention. Keenly aware that I was patronizing an ostensibly public space where the only seats were placed behind gates monitored by security guards, I was eager to part with a few dollars if asked. It took me a moment to register that the woman standing before me, wearing a blue habit and a crucifix around her neck, was asking to borrow my cell phone. She needed to call her elderly father, she said, to tell him that her train would be late, and that she would seek shelter for the night at a convent she had heard of in Boston before continuing her journey. Flooded with a sense of the auspicious, I asked her what her destination was. She said she was heading—as I somehow had felt she would be—to her father’s house on Cape Cod. She named the same town where my in-laws live, to which I, too, was traveling. My husband Jack was picking me up in Providence to drive there, I told her. Would she like a ride?

At that moment, loudspeakers announced our train’s belated arrival, and we shuffled into line together. I noticed a thick volume under her arm, with deeply lined eyes gazing out at me from the cover. The nun—Sr. Maria, she introduced herself—was reading the collected poems of W. H. Auden. Auden was one of my favorite poets, I told her, an inheritor of the Romantic tradition that was my particular academic interest. Sr. Maria was a great reader of poetry, I learned, and had just completed a PhD in Catholicism and philosophy—precisely Jack’s field of study. Minutes after he had retrieved us from the Amtrak station in Providence, the two of them were debating Hegel on ritual. At the end of an hour’s drive, just before we delivered her to her father’s house, Sr. Maria asked me to read aloud from the Auden volume. “The Cave of Making” was her latest favorite, she said. I obliged, and the three of us sat in the car, sharing the sound of the poem.

The town on Cape Cod is large, with a substantial population, especially in the summertime. Against the odds, however, Jack and I ran into Sr. Maria twice the following day. The second time, the three of us burst out laughing—God clearly wants us to be friends, she told us. Jack and I made a date to pick her up after church the following morning so we could all go out to breakfast.

My grandfather was a religious-studies professor and a preacher, and my grandmother was a poet and the spiritual counselor to the monks of a monastery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. When I was very small, she would take my hand and walk me through the fields surrounding their New Hampshire farmhouse, teaching me the poems of Christina Rossetti while my grandfather ran from his study to the pond, where he would skinny-dip even when it was ringed with ice. When my grandparents died, I was left with the relic of faith, but I no longer felt its active presence. I held on to the deeply engrained memory of its rhythms, of its hymns and ceremonies, but I was consigned to a desperately unhappy adolescence. Religion soon belonged to a past, irrecoverable realm of meaning that I conflated with childhood’s visionary gleam.

I cannot tell you exactly what Sr. Maria told us that morning after we picked her up from church. I know that the three of us walked through one of the oldest cemeteries in Massachusetts, and that she preached to me and Jack, and that I knew that I was in the presence of God. I remember looking at the sky and recognizing that, surrounded by epitaphs, I was married to a poet and a philosopher and a believer, and here was an agent of Christ before me, real and forceful, wishing me to receive Christ’s grace.

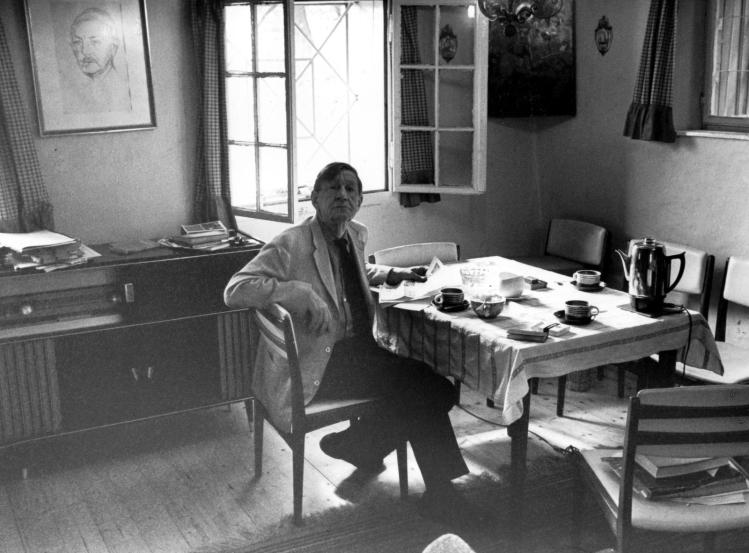

As a young man, W. H. Auden renounced his faith. He wrote his most popular poems during this period of unbelief in his native England—notably the rousing civil-war poem “Spain.” As such works skyrocketed him to fame, Auden recognized that he was being tempted into soaring rhetoric and sweeping moral judgments that failed to reflect the subtleties of real life. Believing such a performance to be unethical, he abjured his position as national icon and fled to America.

In the history of poetry, Auden is a figure of recovery. Amid the fragmentation wrought by early modernism, declared by its practitioners and enthusiasts to be permanent, Auden revived and updated the lyrical forms of the prewar era. In some sense, he succeeded D. H. Lawrence, whose novels and lyric poems insist on the possibility of ecstatic love, of rebirth. Lawrence’s Romantic sublime blooms: his characters throw off the shackles of modernity, of life under capitalist industry, social convention, and sexual jealousy. In his personal life, Auden accomplished many such freedoms. He escaped England for a vibrant New York, where he lived and worked with the greatest artists of the era, fell in love with Chester Kallman, and achieved such commercial success that he could buy himself a farmhouse in rural Austria, where he spent most of his last decade, reading and writing and hosting his literary friends.

But each of those successes was suffused with a sense of loss. Auden could not socialize without a heavy dose of stimulants. The younger, rougher Kallman broke his heart again and again, and their relationship became sexless within a year. The poems he wrote in America were often recapitulations of the poems he had written in England, as the Auden scholar Edward Mendelson has demonstrated, each pair existing in a kind of typographical relation, a before and after. In Austria, again a foreigner, Auden wrote poems mourning his departed friends, colleagues, and idols.

“The Cave of Making” is among the greatest of those elegies. Auden wrote it in 1964 for his fellow poet, travel companion, and beloved friend Louis MacNeice, who had recently died of pneumonia after failing to change out of wet clothes after a storm. The poem’s title refers to the private study that Auden kept on the Austrian property, a “cave” accessible only by external stairs. “I wish, Louis, I could have shown it to you,” the poet tells the dear Shade, who now can keep him company only in absence. At least now that Louis is dead, he can visit Auden without needing to be “met at the station.” Through recollection, and through art, Auden recovers the dead much as he recovers form: namely, with good humor and a desire for human connection but also with the recognition that some essential loss cannot be reversed.

Even within the elegy, this recognition gives rise to guilt about the very enterprise of poetry in a world marked by death. “It’s heartless to forget about / the underdeveloped countries,” Auden writes, referring to his and MacNeice’s shared profession, “but a starving ear is as deaf as a suburban optimist’s.” Beneath the clever, deprecating language of the aesthete is the acknowledgment that Auden’s fellow human beings are suffering in real material ways, and that poetry will not feed them. The same sentiment finds expression in the line that continues to misshape Auden’s critical reputation: “Poetry makes nothing happen.”

It was this conflict between the aesthetic and the ethical that prompted Auden to return to the Church in 1940. It became his late work’s great subject, and the subject of his greatest work, “The Sea and the Mirror.” This commentary on Shakespeare’s The Tempest explores the poet’s deep identification with Prospero, who ultimately chooses not to seek revenge upon his treacherous brother but rather to relinquish his powers of sorcery—including his ability to revive the dead. In so doing, Prospero defies the tragic force, by definition inevitable, that ought to bring the play careening to a bloody close. The choice to “drown [his] book” of spells is famously a moral renunciation of violence. But for Auden, it also introduces a new tragedy: Prospero’s moral choice is also necessarily an aesthetic renunciation—of magical language, of art.

The same conflict animates the series of fragmentary articles that Auden wrote for Commonweal in the early 1940s under the pseudonym “Didymus,” the Greek name of Doubting Thomas. Didymus tells us that a child must look into the mirror to know who he is—a fallen creature in need of salvation—but that seeing his own reflection also tempts the child “by guilt into a despair which tells him that his isolation and abandonment is irrevocable.” Didymus continues, “It is impossible to face such abandonment and live, but as long as he gazes into the mirror he need not face it; he has at least his image as an illusory companion.” The Commonweal pieces make clear that the aesthetic self is the narcissistic, morally suspect one and the ethical self is its Godly antithesis. And yet, Didymus concludes not that art can “do nothing” in the Wildean sense that “all art is quite useless,” but rather that “art cannot make a man want to become good, but it can prevent him from imagining that he already is; it cannot give him faith in God, but it can show him his despair.” Unlike the purely narcissistic mirror—an image that would continue to serve as the third point in a triangle with beauty and goodness in “The Sea and the Mirror”—art makes us feel at a depth beyond the reach of our conscience. We respond to art by feeling not as we ought to feel but rather as we do feel. And in this way, we produce the conditions for God to appear to us. This negative image is, perhaps, the “nothing” that poetry makes happen, the presence through absence that is also the substance of elegy—and, so often, for Auden, of friendship.

“The Cave of Making” and its invocation of absence augured the kind of relationship that would prove available to me and Sr. Maria. Before we parted in Cape Cod, she inscribed her email address on the floral notecard she had been using as a bookmark in the Auden volume and gave it to me. I promised to write. Over a year later now, the card still lies in my bedside table, unused.

I also have failed to commit to attending weekly Sunday worship as I had promised her I would. Now, though, in a turn that I didn’t anticipate, the slaughter in Gaza has returned me to prayer. I wonder if Sr. Maria’s order, committed to protecting children in the world’s most tumultuous places, has traveled there to lend assistance. I wonder what she is praying and working for.

In moments of grief such as the one in which we find ourselves now, America turns to Auden. In the days following 9/11, newspapers printed “September 1, 1939” in its entirety, including the line that the poet himself famously denounced: “We must love one another or die.” Auden took to omitting the poem’s last stanza altogether before making the crucial emendation of “or” to “and”: “We must love one another and die.” We die no matter what, he told an interviewer.

The first, more rousing version—the more popular and more politically useful one—concludes in a moralistic injunction that draws upon the individual instinct for self-preservation. In its grand rhetoric, it denies an essential conflict between the good, the beautiful, and the mirror. “To love one another and die,” by contrast, proposes a Christian temporality in which death is always imminent, always recent. And, indeed, Auden made his revision after World War II had claimed millions of lives. In Auden’s mature work, death conditions ritual: ashes to ashes, dust to dust. To anticipate meaning in the Christian tradition is also to anticipate death.