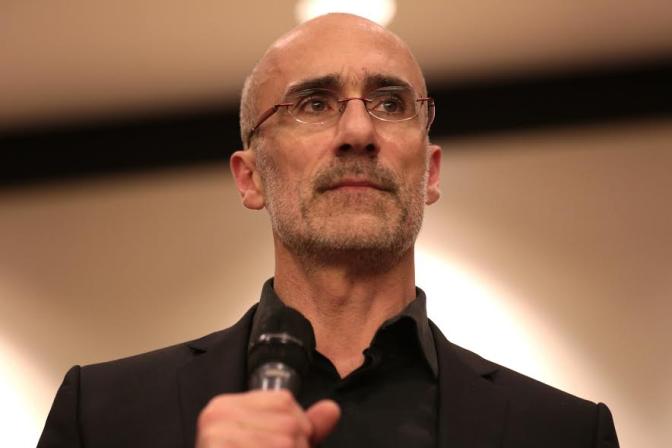

In an article published a few months ago in America magazine, Arthur Brooks—president of the American Enterprise Institute—described his conversion to capitalism. His basic argument is that the free-market system has lifted an unprecedented number of people out of poverty, which means that opposition to free enterprise is deeply misguided.

The frustrating thing about these debates is that the terms are rarely defined. Catholic social teaching certainly gives a qualified endorsement of the free-market system, but not in the way meant by Brooks. People like Brooks tend to conjure up a stark dichotomy between a virtuous free market and oppressive state control. They obscure the fact that Catholic social teaching has long condemned both extremes—libertarianism and collectivism (which Pope Pius XI dubbed the “twin rocks of shipwreck”).

Between these two extremes, Catholic social teaching insists that economic activity be ordered toward the common good. One aspect of this is “social democracy” or the “social-market economy”—a market economy, yes, but one in which the state ensures that goods and services essential to human flourishing but not necessarily provided by the free market are made available to all; one that corrects for the swings of economic fortune that are inevitable in any market economy and regulates business to better align private behavior with the requirements of the common good. This is why Pope Benedict XVI was able to declare that “democratic socialism was and is close to Catholic social doctrine and has in any case made a remarkable contribution to the formation of a social consciousness.”

But Catholic social teaching also insists that solidarity cannot be wholly outsourced to the state. Again, Pope Benedict argued that market activity cannot be just about making money for its own sake, but must embody “authentically human social relationships of friendship, solidarity, and reciprocity.” This means that business must orient its activities toward the common good—producing goods and services that meet genuine human needs, prioritizing dignified work and decent wages over profits, and embracing a keen sense of social and environmental responsibility. It’s not only about creating wealth, but creating it sustainably and distributing it justly.

This is the kind of market economy favored by Catholic social teaching. But is it the kind favored by Brooks? Probably not. Brooks is known for painting a stark contrast between American-style free markets (good) and European-style social democracy (bad), and he has spent years castigating the centrist Barack Obama as an enemy of free enterprise. Nor is there any hint that he believes businesses have a responsibility to look beyond profit.

Brooks—like his ideological comrade Paul Ryan—seems under the spell of libertarianism or market fundamentalism, an ideology that puts economic freedom first. This ideology insists that all market rewards are fairly and justly earned and that the government’s role in economic affairs should be severely restrained. And libertarians insist that the role of business is to maximize profit, typically equated with shareholder value.

This is something of a shell game. Brooks never uses the word “libertarian” in his America essay, which offers him plausible deniability. This is unsurprising, because such an ideology—by detaching individual freedom from communal responsibility, elevating self-interest over solidarity, and upholding freedom from coercion over the universal destination of goods (which Pope Francis deems a golden rule of social conduct)—is utterly incompatible with Catholic social teaching. It is a rock of shipwreck.

Brooks credits five forces for the reduction of poverty worldwide—globalization, free trade, property rights, the rule of law, and the culture of entrepreneurship. These forces are certainly important. But reducing all material gains to these forces is simplistic, and Brooks is wrong in inferring that a consensus among economists supports his ideology. Economic development is actually far more complicated than he lets on. Yes, trade is beneficial, but so is investment in health and education. When it comes to fighting poverty, a country might face natural impediments—including being landlocked, mountainous, without access to energy resources, prone to disease, or highly vulnerable to natural disasters. It could be stuck with self-serving and short-termist policies adopted by self-interested elites. There could be instability and conflict, including through the intervention of global or regional powers. Or there could quite simply be a poverty trap, whereby a country has good intentions but is too poor to make the basic investments needed to end deprivation. The bottom line: it’s complicated. To claim that the 800 million or so people still mired in extreme poverty can escape their plight through Brooks’s five factors is misleading and unserious.

From this wider perspective, any explanation of the economic rise of the United States must account for negative factors like the exploitative system of slavery and positive factors like an early push for mass education. It must also account for the devastation of Europe after the war, combined with the fact that the United States took over a role vacated by the United Kingdom—deploying military power to extend economic power. The Japanese postwar economic miracle had its roots in the deliberate and heavy-handed strategy of the U.S. occupiers to widen the distribution of income and ownership of wealth. Turning to China, the extraordinary reduction of poverty over the past few decades came from moving away from ruinous collectivism, not toward a Western-style free market, but toward a state-directed capitalism in which property rights—and human rights, more generally—are still at the mercy of the Chinese Communist Party. The recent progress in reducing poverty in sub-Saharan Africa was partly due to the end of the Cold War, combined with debt relief and development aid delivered under the aegis of the Millennium Development Goals. To reduce the reduction of poverty to such factors as property rights, entrepreneurship, and the magic of free markets is folly in the service of ideology.

Yet this ideology has made great inroads over the past few decades. The idea was deceptively simple: if government restraints on free enterprise were eased or removed, this would unleash a wave of dynamism and wealth creation. This idea was used to justify policies like deregulation, privatization, cutting government programs, reducing upper-income and capital taxes, and curbing the power of labor. After demand-side policies associated with Keynesianism lost legitimacy during the stagflation of the 1970s, these new supply-side policies were supposed to boost long-term growth, which entails boosting productivity. But this never happened. In his magisterial work, The Rise and Fall of American Growth, Robert Gordon shows that output per hour was much lower after 1970 than in the middle of the century. Even worse, total-factor productivity—the best measure of the pace of innovation—was actually three times higher in the earlier period (1920–1970) than afterwards. This earlier period was dominated by social-democratic policies under the auspices of the New Deal. It reflected a spirit of solidarity with high levels of social trust and economic growth that was broadly shared among the different social classes. In contrast, while the Reagan revolution never delivered its promised dynamism, it did deliver higher inequality, lower social trust, greater corporate power, and increasing financial instability.

In Europe, too, the social democratic settlement enjoyed phenomenal success in the decades following the war. Yet people like Brooks disparage the European social model. An un-nuanced analysis might note, correctly, that real GDP per capita in the Euro Area is only about 70 percent of what it is in the United States. But this is misleading on a number of levels. GDP per capita is a product of three separate factors—productivity, the employment rate, and average hours worked. It turns out that productivity in Europe is not that different from productivity in United States (although it is weaker in southern Europe). Nor is employment as different as some imagine, especially for prime-age workers. The big difference is in average hours worked, which reflects a conscious choice to forsake extra work in favor of family and leisure. This is a feature of Europe’s social market, not a bug.

Not surprisingly, Europe beats the United States on a host of human-development and quality-of-life indicators. Poverty and inequality rates are lower. Life expectancy and infant-mortality rates are better. And yes, this is in large part due to extensive safety nets. In disparaging these programs, Brooks fails to mention their genuine achievements, or the fact that the European countries in the worse economic condition are precisely those, in southern Europe, with the most underdeveloped welfare systems. Nor does he mention the fact that the United States has effectively stopped fighting poverty in the aftermath of the Reagan revolution. As Anthony Atkinson—one of the giants in the field—pointed out, no advanced economy has managed to achieve a low level of inequality or relative poverty with low levels of social spending.

In sum, the European social model shows that prosperity can go hand in hand with fairness and cohesion. This is especially the case in Scandinavia, the quintessence of modern social democracy, where citizens readily accept high taxes to ensure that everyone has access to quality education, health care, child care, and other social services. Despite the claims of libertarians, Scandinavia shows that it is perfectly possible for a modern economy to be simultaneously productive, fair, compassionate, sustainable—and happy.

The last point is important, because Brooks devotes so much attention to happiness. He is right to do so, although the evidence fails to back up his claims. In this year’s World Happiness Report, half of the top-ten happiest countries in the world are Scandinavian—Norway, Denmark, Iceland, Finland, and Sweden. Rounding out the top ten are Switzerland, Netherlands, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia. The United States ranks fourteenth.

A key finding of the happiness literature is that, above a certain minimal threshold, money does not buy happiness. In the United States, while income per person has risen roughly threefold since 1960, happiness has not. This is known as the Easterlin Paradox. But this finding would not have surprised Aristotle, who understood that happiness was driven by such factors as relationships, meaning, and purpose. Modern happiness studies affirm this ancient instinct. Brooks himself points to a study showing that happiness derives from “intrinsic goals” rather than “extrinsic goals” like wealth or fame. What tends to matter most for happiness is the quality of social relations and the ability to make a social contribution. And indeed, the World Happiness Report demonstrates that happier countries enjoy stronger social support, higher levels of trust and generosity, and a greater ability for people to realize their capabilities. Even more, it shows that social factors have a larger effect on happiness than financial factors. Jeffrey Sachs has shown that happiness is declining in the United States not because of income, but because of a mounting social crisis—rising inequality, isolation, mistrust, and corruption. And it is precisely the libertarian policies favored by Brooks that drive this crisis. Sachs also demonstrates that “economic freedom”—measured by a Heritage Foundation index capturing such elements as property rights, small government size, low levels of regulation, and open markets—does not produce happiness. In short, libertarianism is at odds with human nature. The church has known this all along.

One of Brooks’s main arguments is that income inequality is nothing to worry about, and that the real focus should be on equality of opportunity. The gist of his argument is that, while income inequality in the United States might be high and rising, this is not true for consumption inequality. This is a peculiar argument. It is of course important to look at consumption. But a quick perusal of the recent evidence shows that consumption inequality has tracked income inequality quite closely over the past few decades. Brooks is simply wrong. And anyway, the focus on income can easily be defended on the grounds that income provides advantages that go beyond consumption.

What Brooks is trying to say is that because poor people have access to goods that their predecessors did not, such as air-conditioning and color television, we should not worry too much about inequality. But this appeal to historical comparison is actually ahistorical; it overlooks the fact that poverty and wealth are always contextual. What matters is not that even many poor Americans now own devices and enjoy conveniences that would have astonished the richest robber baron of a century ago. What matter are the material conditions that allow one to participate and flourish across the various dimensions of life in a specific time and place.

Brooks also downplays distributional concerns by appealing to the familiar fact that, while inequality within countries has risen sharply in recent decades, inequality between countries has fallen: the gap between the rich and poor countries is shrinking. This development reflects the remarkable achievement of countries like China, which transformed itself from an impoverished village-based nation to a middle-income economy within a matter of decades. Nevertheless, the nation state remains the locus for deliberation on the common good and the most effective political instrument for distributive justice. We therefore have good reason to be concerned about growing inequality within our borders, since that is the inequality over which we have some control as citizens. Why should the rise of a large middle class in the developing world, welcome as it is, justify an increasingly uneven and inequitable division of wealth in the developed world?

The real problem with inequality is that it severs the sense of shared purpose necessary for the realization of the common good. This is an insight that goes all the way back to Plato and Aristotle, who feared that when the gap between rich and poor grows too large, the rich become more attached to their wealth than to their civic obligations. The founding fathers of the United States fretted about oligarchy for similar reasons. This older insight seems to have been largely forgotten, but it is highly relevant today—because inequality has returned to Gilded Age levels, and because market ideology has detached the creation of wealth from social duty.

Today, as during the Gilded Age, inequality is being driven by technology and globalization. But in both periods, it quickly developed a momentum of its own. This self-perpetuation is a key theme of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, which argues that inequality is endemic to capitalism, since the financial return on wealth tends to exceed the rate of economic growth over long periods of time. Branko Milanovic, another leading expert in global inequality, has reached similar conclusions with somewhat different reasoning. Milanovic argues that while inequality in each period has been spurred by underlying economic factors, it soon ushers in policies that favor the rich—cuts for upper income and capital taxes, curbs on the bargaining power of labor, greater tolerance for monopoly power, and looser restraints on financial innovation. From this perspective, market ideology might be nothing more than a mask for plutocracy.

The evidence suggests that in a highly unequal society the sense of an all-encompassing common good tends to evaporate. As the rich grow increasingly segregated from the rest of society and more convinced that wealth is always and only the product of individual effort, their circles of fraternity and ethical horizons tend to narrow. Wealthy individuals and powerful corporations increasingly put narrow financial gain over the broader common good. And since an unequal distribution of income translates too easily into unequal access to political power, the rich have the ability to get what they want and keep what they have. In this retreat from the common good, it is the poor who get trampled.

The relationship between economic growth and inequality is complicated. Neoclassical economics has traditionally insisted on a trade-off between equity and efficiency; it has warned that efforts to reduce inequality can undermine incentives to work, save, and invest. But in present circumstances, this doesn’t seem to be the case. The IMF has shown that income inequality is associated with less sustained economic growth and that growth trickles up from the poor and middle classes, not down from the rich.

Why might inequality hurt prosperity? There are a number of reasons. First and simplest, demand is lower in a more unequal economy. This is because the rich spend less of their income and save more. Second, inequality goes hand in hand with a decline in trust and social capital, which in turn harms productivity and increases the likelihood of social strife and political instability. Third, because the common good is undermined, inequality reduces the likelihood of growth-enhancing investments in areas like infrastructure, education, decarbonization, and research and development. Fourth, inequality tends to be associated with corporate rent-seeking—the tendency to extract rather than create wealth, driven by such factors as monopoly power, corporate concentration, and weak corporate governance.

There is a fifth reason that is directly relevant to Brooks’s argument: inequality of income is directly tied to inequality of opportunity. This is because inequality magnifies the social advantages of the wealthy. Plutocracy rewards mediocrity and undermines meritocracy. Unsurprisingly, there is a strong empirical association between income inequality and intergenerational mobility—the famous “Great Gatsby curve”—and both are better in Europe than in the United States. The bottom line is that if Brooks truly cares about inequality of opportunity, he should also care about inequality of income and wealth.

In downplaying the detrimental effects of American inequality, Brooks draws a distinction between the United States and other highly unequal regions in the world, such as Latin America. He argues that, in these other places, prosperity depends more on power and privilege and less on the free market. He’s right about that. But he fails to note that as the United States inches ever closer to Latin American levels of inequality, the corrupting effects of plutocracy become ever more embedded in our own system. It is important to point out that in Latin America, the pattern tends to be one of oligarchic dominance interspersed by disruptive populist backlashes—and both harm the common good. Given recent trends, perhaps the United States is destined to go down this path. Perhaps last year’s election actually represents a terrifying regime shift. The catch, of course, is that Donald Trump is a plutocrat masquerading as a populist.

The corrosive effects of inequality extend well beyond the economic dimension. In a pioneering study titled The Spirit Level, social epidemiologists Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett showed that people in more unequal societies trust each other less, fear each other more, participate less in community life, and are more prone to violence. In the United States, Robert Putnam and others have documented a decades-long decline in social capital, civic purpose, and associational life—all in tandem with rising inequality. Wilkinson and Pickett tie fraying social relations to a litany of social ills—including poor physical and mental health, drug abuse, weak educational attainment, obesity, teenage pregnancy, and illness among poor children. The social dysfunction is also tied to the neoliberal ideology that is driving much of the inequality. This ideology stunts not only solidarity but self-worth. It sends a toxic mixed message—telling people that happiness comes from consumerism and that market outcomes reflect moral desert: those who do not succeed have only themselves to blame. Not surprisingly, the growing prevalence of this outlook has been linked to an unprecedented epidemic of stress, loneliness, and mental illness. In the United States, the recent rise in opioid addictions and the documented decline in the life expectancy of working-class white people adds to the long list of social pathologies. Having a color television or air conditioning—to use Brooks’s favorite examples of the luxuries of the poor—is a paltry consolation prize in the face of massive social collapse.

Brooks is well aware of the claims that market ideology—by emphasizing such traits as selfishness, competitiveness, and boundless acquisitiveness—can undermine virtue. Yet he has no real answer other than to say that “systems are fundamentally amoral” and that what matters is the morality of the people who participate in the system. But this view is not in accord with Catholic social teaching. In Caritas in veritate Pope Benedict XVI states explicitly that the economic sphere cannot be regarded as “ethically neutral”: “It is part and parcel of human activity and precisely because it is human, it must be structured and governed in an ethical manner.” Indeed, as the theologian David Cloutier pointed out in his own response to Brooks, it is ludicrous to conjure up a powerful economic system that depends on such vices as fear and greed, and then claim that the problem is only with the vices, not with the system itself.

The bottom line is that the toxic interplay of inequality and ideology gives rise to an economic system antithetical to solidarity. It gives rise to what Pope Francis has described as the economy of exclusion, the throwaway culture, and the globalization of indifference.

In the U.S. context, this can be demonstrated with a couple of topical examples: health care and climate change. In health care, the attempt to sabotage the Affordable Care Act is a brazen ideological assault on a form of solidarity that calls for the young and healthy to subsidize those most in need—the old, the infirm, expectant mothers. The debate has been framed by Republicans as a matter of consumer choice, not compassionate care. In direct contravention of Catholic social teaching, this ideology insists on consigning a basic human right to the whims of the market. Worse, the money saved from cuts to Medicaid and insurance subsidies is to be transferred to the rich by means of tax cuts.

The case of climate change is even more egregious. In the United States, a combination of libertarian ideology and the lust for profit lies behind the scandal of climate change denialism and the intention of the new administration to abrogate responsibility for cutting carbon emissions. This puts the planet on course for environmental disaster, and is tantamount to a direct assault on the poor of today, as well as future generations. It is one of the great moral issues of the twenty-first century and a core theme of Pope Francis’s encyclical Laudato si’. And it is exhibit A of what harm can be done by the ideology Brooks defends in his America article. I have no doubt that he is sincere is his desire to improve human well-being, especially the plight of the poor. Yet the institution he directs—the American Enterprise Institute—takes money from climate-change deniers and hard-line libertarians, including the Koch Brothers. Such people pose a grave threat to the common good, and no amount of rhetoric can make their positions compatible with Catholic social teaching.

Our situation today is perilous. At a moment when we desperately need political consensus to address collective problems, such consensus seems farther out of reach than ever before. In its place, we have the false consensus of neoliberalism, which tells us that there is no alternative to the economic model Brooks celebrates. As Mark Carney—governor of the Bank of England—suggested, unchecked market fundamentalism can lead capitalism to devour its own children. Or as Pope Francis puts it, this economy kills. What we urgently need is a re-orientation of the economy toward the common good. We need policies that set markets in the kind of moral framework promoted by Catholic social teaching. This will require both personal and structural change; it will require that we spend our money differently, judge politicians differently, and run our businesses differently. In other words, it will require a genuine conversion—away from the creed preached by Arthur Brooks.