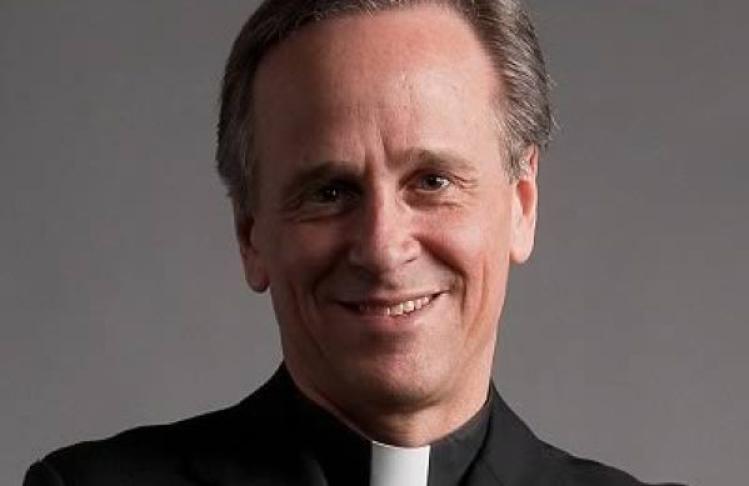

Earlier this week, Commonweal contributing editor John Gehring spoke with University of Notre Dame President John I. Jenkins. The conversation touched on the tone and tenor of this year’s election, speeches given at Notre Dame by President Obama and Philadelphia Archbishop Charles J. Chaput, and why New York Cardinal Timothy Dolan was the best thing about this year’s Al Smith dinner. This interview was conducted by email.

John Gehring: Now that we’re nearing the end of a presidential election what is your assessment of this very intense and very unusual political season?

John Jenkins: No doubt the campaigns have reflected some anxiety, anger, and resentment in the nation at large, and we must try to understand these attitudes in the electorate. But rather than trying to understand and rise above them, as leaders should, the campaigns have often simply channeled these negative emotions. This has made the substance and tone of much of the discussion not only unpleasant and uninspiring, but the acrimony and divisiveness are not healthy for our democracy.

JG: Some Catholic commentators and politicians have argued that the Clinton campaign is anti-Catholic because of a few lines in hacked e-mails released from Wikileaks. Anti-Catholicism is a serious charge. What is your perspective?

JJ: I’m reluctant to draw many conclusions from private correspondence leaked without permission. We have perhaps all said things in unguarded moments that we would not want printed in newspapers. I am far more concerned about policies of the Democratic administration and Democratic Party that infringe on the rights of religious institutions and practices and open the door for using taxpayer dollars for abortions, to which many Americans have profound moral objections. Those are steps that would show a lack of respect for Catholics and their institutions.

JG: As you well know, Catholic identity is a contentious topic, whether we’re talking about the issues Catholic should prioritize in the voting booth or who is invited to speak at Catholic universities. You’ve been critical of groups like the Cardinal Newman Society that use aggressive tactics and seem to want to reduce Catholic identity to a few issues. Is Pope Francis helping us think about Catholic identity in different ways?

JJ: Pope Francis has taught us by his example how we can witness with our lives and actions to our faith and moral principles, but still engage respectfully with those who disagree. He’s urged us to find a “new balance,” going beyond the few wedge issues of our politics, so we do not lose the “freshness and fragrance of the Gospel.” He has done this not through angry speeches, but through the powerful symbols and examples of embracing a badly deformed man, welcoming refugees to the Vatican, strolling through a shanty town in Rome, visiting a home for the elderly, washing the feet of prisoners on Holy Thursday, and going to a hospital for newborns. He has reminded us that the way we live our lives is the most important expression of our Catholic identity.

JG: At a recent speech at your university, Archbishop Chaput of Philadelphia said that “we should never be afraid of a smaller, lighter church if her members are also more faithful, more zealous, more missionary.” He specifically criticized Vice President Joe Biden and Senator Tim Kaine, suggesting they are Catholic in name only because of their position on abortion. What was your reaction to his speech?

JJ: I find the latter statement baffling. Though the archbishop may rightly argue that they are objectively wrong in their positions, I don’t understand how he can presume to know the consciences of Vice President Biden and Senator Kaine sufficiently to question the genuineness of their faith and condemn them personally. As Pope Francis says in Amoris laetitia, pastors must “make room for the consciences of the faithful, who very often respond as best they can to the Gospel amid their limitations, and are capable of carrying out their own discernment in complex situations. We have been called to form consciences, not to replace them” (no. 37). As for the former statement, we should only be afraid if the church is smaller because of our failure to welcome people and preach the Gospel in a way that touches their hearts.

JG: Speaking of speeches at Notre Dame, it’s been seven years since you invited President Obama to give the commencement address. Looking back and reflecting on that experience, what surprised you and what did you learn?

JJ: I have reflected a great deal on that event, and continue to do so. I cannot give you a complete answer in a few sentences. But I would say that I was struck at that time by the vehemence of the anger from various sides, and the anger was in many cases directed at those who share a Catholic faith. I understand that such anger, such vehemence arises from sincere and passionate conviction, but I believe expressing it in such vitriolic terms gets us nowhere. I’ve never met anyone who has changed his mind or deepened his faith because he has been confronted with such angry condemnations. But I’ve seen many dig in their heels and becoming disenchanted with the church because of these kinds of denunciations from coreligionists. We have to find a better way to witness to our faith and our convictions.

JG: After the election, there is obviously a lot of work to be done to heal and unify the country. You’ve always championed civility and common ground. Do Catholics have something particularly distinctive to contribute in this effort?

JJ: I live near Amish communities in northern Indiana and I have the greatest respect for such faithful people. They attempt to live their faith more fully by separating themselves, as far as possible, from the wider culture and its influences. That has never been the teaching of the Catholic faith. We are called to serve the common good by engaging with political and other institutions, even in our pluralistic society. We bring to that effort Christ’s command to love and the grace that helps us live that love. To the extent that we sow love where there is hate and light where there is darkness, each in his or her own walk in life, we can heal, enlighten, and unify.

JG: The Al Smith dinner attracted a lot of attention this year. What did you think?

JJ: Best thing about it: Cardinal Dolan got the candidates together for a brief prayer before going out on the stage. Worst thing about it: it was another reminder of how far we are from the amity between opposing sides that is needed for effective governance.