Steven Englund reminds us that no single event signals the end of a story. The Vatican II document Nostra Aetate seemed to conclude decades of struggle over a new Catholic position on non-Christian religions and on Jews in particular. Yet the story is far from over, Englund warns; indeed, as he demonstrates, anti-Judaism continues a robust life. It was one thing for the church to condemn anti-Semitism in 1965; but it is a very different thing for it to step back and rethink all the writings, prayers, and hymns from many centuries that portrayed Judaism as a dead religion and Jews as a cursed people.

The issue may seem esoteric to Catholics who listen to Scripture readings Sunday after Sunday and may hardly notice any anti-Judaism. To get an inkling of the power of this anti-Judaic legacy, I recommend reading a gospel in one sitting. Or better yet, watch the 2003 film The Gospel of John with a Jewish friend. At times, you will both cringe as Jesus denigrates Jewish authorities and outdoes—indeed, seems to supersede—their teaching.

[See all the essays included in "Getting Past Supersessionism: An Exchange on Catholic-Jewish Dialogue."]

For my part, I sensed the depth of the problem only after chancing to read John P. Meier’s 1978 gospel commentary The Vision of Matthew. Meier is a Catholic priest and highly regarded New Testament scholar; his book comes “warmly recommended” by Raymond Brown, perhaps our time’s most respected Catholic Scripture scholar, and bears an imprimatur and nihil obstat. So what is its message concerning the Jews? Where Nostra Aetate describes the Jews as “most dear to God,” in Meier’s Matthew, “the Kingdom of God is taken from this people and given to another people, the church, which will bear its fruits (21:43).” “A fundamental choice,” Meier writes, “involving the confession or the denial of Jesus as Messiah, leads to a fundamental change in the identity of the people of God. The fatal decision is made by the whole Jewish people in 27:25.” Meier describes a second coming of Jesus in which “Jerusalem and the Jews will be forced to acknowledge and hail the coming one. But on that day he will come as judge.... On that day it will be too late.” According to Meier’s Matthew, the Jewish people therefore live without hope.

Meier would surely argue that he was producing theological scholarship and bound to represent what the author of Matthew meant. But this is a book for a general audience. Shouldn’t there at least be a caveat? Did he not see the poison emanating from these lines? If he did, why then did he reprint the 1978 edition without changes in 1991?

It may be unfair to single out Meier, since one can find similar interpretations of Matthew 21:43 (the story of the evil vintners) in postconciliar works of such renowned Catholic theologians as Joachim Gnilka or Wolfgang Trilling. Indeed, as far as I can tell, prior to 1965 no Christian scholar held these passages from Matthew to mean anything other than that the church had superseded the Jewish people. Yet in recent years many theologians have come to regard this and other anti-Judaic texts as interpretations dependent on context. For centuries, that context was hostile to Jews. Today, however, scholars such as Daniel Harrington of Boston College hold that Christ’s words in Matthew 21:43—“the kingdom of God will be taken from you”—address not the people of Israel, but its leaders.

And yet I look at my copy of Meier’s The Vision of Matthew and find on the back cover an endorsement by none other than...Daniel Harrington. So what is the average Catholic to make of all this? The church’s teaching authority on this topic is all but inaudible. In 1974 a Commission on Religious Relations with Jews was set up in the Roman Curia to promote “effective and just realization of the orientations given by the Second Vatican Council”—yet in four decades it has issued just three statements, one of which devotes but three pages to “Jews in the New Testament.” This is not much to weigh against the mountain of anti-Judaism in church tradition. (There are also statements of national bishops conferences, helpfully collected at Boston College’s website on Christian-Jewish Relations.) If the Holy See cares about this tragic legacy, it should issue a guide for Catholics hoping to read the New Testament in the spirit of Nostra Aetate.

YET PERHAPS EVEN today’s church leadership is unaware of the depth of the problem. Last October Fordham Scripture scholar Michael Peppard wrote enthusiastically (on dotCommonweal) about the new pope’s “total commitment to the Jews.” Just the previous day, however, Boston College’s Robert Imbelli posted a statement by Francis on the Communion of Saints. This Communion, the pope wrote, goes “beyond earthly life, beyond death and endures forever.... It is a spiritual communion born in baptism and not broken by death…” What about the non-baptized? According to Cardinal Walter Kasper (president emeritus of the Commission on Religious Relations with Jews), Judaism is “salvific” for Jews, because—quoting Nostra Aetate—“God is faithful to his promises.” Why then does Francis exclude Jews from the Communion of Saints?

These matters will doubtless strike most Catholics as esoteric. Why care whether leaders of the church have absorbed the teaching of Nostra Aetate? Most of us, after all, have learned about religious tolerance from other sources—films on the Holocaust, for example, or history lessons in school. We don’t need the church to tell us about the costs of religious hatred; for that we have the liberal principles of our secular order, a marketplace of ideas (and religions) where everyone may speak and no one imposes his or her views upon anyone else. Who needs Nostra Aetate?

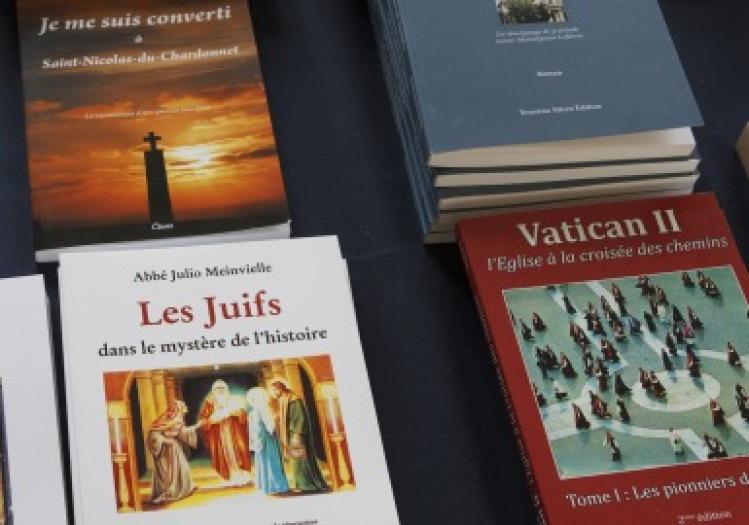

While this liberal consensus has undoubted virtues, it may serve to reinforce Catholics’ insensitivity to anti-Judaism, whose embers continue to smolder—and occasionally blaze up. Last year a book appeared in Poland by a prominent Catholic [*] claiming the Jews were collectively responsible for killing Christ. No one in the Polish episcopate rose to warn Catholics that this book, with abundant citations from works of Catholic theology, contradicts church teaching. Presumably, they had not taken the time to work out the implications of Nostra Aetate for themselves.

Perhaps even Steven Englund does not fully appreciate the revolution unleashed by Nostra Aetate. Its section on the Jews is not about “parity” and not even about tolerance; to tolerate, after all, means to endure, to “put up with.” Far more than putting up with Judaism, Nostra Aetate celebrates the church’s origins in Judaism, and asserts that God holds the Jews “most dear.” The church says such a thing about no other religion or people. Nostra Aetate does not preach supersessionism. Yes, it does say the exodus of the Jewish people “foreshadows” the salvation of the church. But keep in mind that where a “shadow” falls depends upon who is viewing it. Americans might say that the Magna Carta foreshadows the Constitution, yet we would not expect the British to share this perspective. Pluralism means understanding and respecting the other’s viewpoint, not sharing it.

More important, Nostra Aetate recognizes Jewish holiness as existing in its own right, not merely as part of a Christian script. It speaks of the church as the “new people of God,” but also says that God does “not repent of the gifts he makes or of the calls he issues.” These lines are taken to mean (in several statements of John Paul II) that God’s covenant with the Jews remains in full force. Mysteriously, the old and the new people of God coexist.

And finally, what about the Jewish “no” to Jesus? No one anguished over this more than St. Paul; but he also knew that without it, the Good News would not have spread beyond Israel to the world. And so he concluded these reflections with an apt and humbling question: “Who has known the mind of the Lord?”

[* An earlier version of this piece incorrectly referred to the author of the book that appeared in Poland as a Catholic priest; it has since been revised to reflect the correction.]