In 2001 I held a visiting philosophy professorship at Georgetown University in Washington, where my route home took me down a long, steep stone stairway between two high walls. Known locally as the “Exorcist steps” on account of their appearance in the famous film of that name, they have since been designated a D.C. landmark. At the time, I was writing a book on the nature of religion, and in a chapter on the meaning of history drew parallels between the story of spiritual conflict related in The Exorcist, and the sense of a battle between good and evil prevalent in the wake of 9/11.

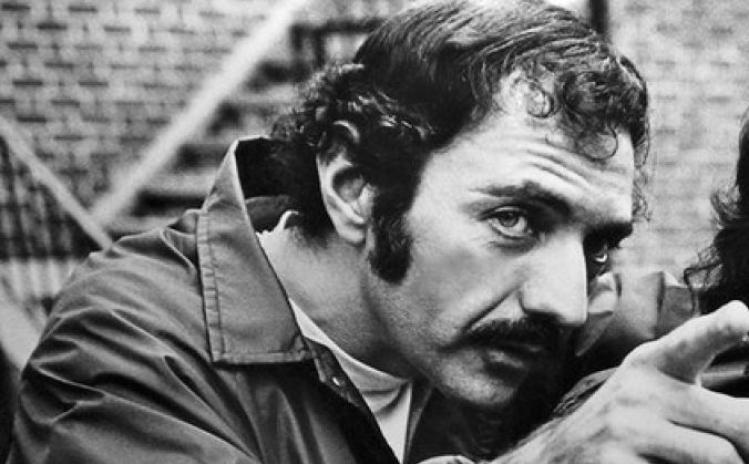

Four years later, I learned through a mutual acquaintance that William Blatty, the author of the Oscar-winning screenplay and of the novel upon which it was based, was intrigued by the use I had made of his theme. He invited me to his home in Bethesda, Maryland, and explained that as a philosopher I might be interested in his own ideas about good and evil. The experience was memorable.

“Bill” Blatty was born in New York to Lebanese parents who immigrated to the United States on a cattle boat. His great uncle, Germanios Mouakad, was a bishop of the Melkite Catholic Church and a leading middle-eastern philosopher. After Jesuit schooling in Brooklyn, Blatty went on to Georgetown and from there to George Washington University to study English. He excelled throughout his studies, and in 1951 entered the Air Force, becoming chief of the policy branch of the Psychological Warfare Division. Following a period in Beirut with the U.S. Information Agency, Blatty moved to California and there began publishing novels. This led to script-writing, and by the mid-1960s he was working with Blake Edwards on a series of films, including the 1964 Pink Panther sequel A Shot in the Dark. By the end of that decade screenwriting work was drying up, so Blatty took himself off to a cabin to explore an idea that had been with him since college days. That “exploration” resulted in the novel The Exorcist in 1971, followed in 1973 by the legendary film.

Various accounts of the genesis and meaning of The Exorcist have been given. Here is what Blatty told me.

When I was an undergraduate we were shown a number of petals that were said to have come from a miraculous fall of flowers that occurred in in 1948 in Lipa in the Philippines. You could see on each petal an image of a woman, which because of associated apparitions was presumed to be the Virgin Mary. I noticed that my classmates were filled with a fervent desire to believe, and I accepted that if Christianity is true then nothing is as important as faith and the life of the world to come. Later, while still at Georgetown, I heard about an exorcism that had been going on partly in the area, and which was sanctioned by the Church. I thought that if this could be confirmed it would help answer questions about belief, because if there were demons then why not angels, and surely there was likely to be a God.

Years later and having little else to do I thought ‘why not go back and investigate the exorcism case?’. I discovered the name of a priest involved, Fr. William Bowdern. He had kept a diary of events and told me that he had no doubt it was ‘the real thing.’ Listening to the priest and learning other details of the case, including experiences witnessed by non-religious observers, I felt that this was more than a story; it was testimony to a supernatural reality.

The book was an enormous success, with 13 million copies sold in the United States alone; the film quickly acquired a status it has never relinquished. But Blatty felt that his real purpose had been lost sight of. He tried to correct this with a sequel, Legion, which itself was later filmed. He had asked that before we met I should read the book, and in doing so it became clear that behind the stories of possession and violence lay a mind trying to answer two of the most ancient philosophical questions: what is the source of order in the universe? and what is the meaning of evil?

Discussing his ideas, Bill Blatty handed me a sheaf of papers, including part of the draft of another book he was then working on, Dimiter (which was published in 2010). In it he sets out his metaphysical theory, again through the medium of a story, this one set in Albania and in Jerusalem. A character, this time a priest, explains the combination of order and suffering, of good and evil. “ ‘Before the beginning,’ urged the priest, in some Elsewhere, we were a single titanic being. Then something happened, some decision was made that we dimly recollect as The Fall. A means of salvation was offered. We took it. Exploding from oneness into multiplicity, we became the physical universe, space-time, light cloaked in matter, for in no other way but in bodies could we risk, could we grow and evolve back into ourself … . Consider: all matter is finally energy. And what is energy finally? Light! … ‘You were once a bright angel.’ Do you see? We are Lucifer, the ‘Light Bearer’ ....”

We had been talking for a few hours in Blatty’s study. On one wall hung photos, props, posters, and other material charting stages and accomplishments in his career, and beneath these stood a glowing upright juke box in the classic style. On the other side of the room, beneath a light that inexplicably and irregularly dimmed and brightened, sat my daughter Kirsty, who had come along to listen to our conversation. Before leaving we moved through to a lounge equipped with a cocktail bar, on one shelf of which stood the Oscar for The Exorcist. Blatty handed it to Kirsty, saying, “It’s a metaphor for Hollywood: gold-plated but base metal beneath the coating.” We were back in the familiar world of the ordinary—as ordinary as holding an Oscar in the cocktail lounge of a mansion in Maryland may be.

As I made my way from his house my mind returned to the events of September 11, to the subsequent talk of inhuman evil, and to the usual reading of The Exorcist as a film about demonic possession. If Blatty was right, then the battle of good against evil is not one between a god in heaven and a devil in hell, but rather is a struggle within the world between aspects of a single creature, us, struggling to make its way back, of its own accord, to where it once came from—and where it hopes to be again: in the company of God. Contrary to what many of his fans suppose, Blatty’s mystery tales are not horror stories but metaphysical allegories in the tradition of the ancient, Near Eastern cultures: stories his very ancestors might have told.

Finally, a word on the case that first prompted his interest in the supernatural. This involved a twenty-one-year-old Carmelite novice, Teresita Castillo, who in 1948 reported that Mary appeared to her several times in the convent garden, asked that a statue of her be placed there, and identified herself as “the Mediatrix of all Grace.” In 2015, the archbishop approved devotion to “the Virgin of Lipa,” declaring the Marian apparition to be worthy of belief. But within months the Holy See declared that the “evidence and testimonies exclude any supernatural intervention in the reported extraordinary happenings—including—at the Carmel of Lipa.” Sr. Teresita died in November 2016, two months before Blatty. They were both eighty-nine.