To comprehend fully the anarchic spectacle of Donald Trump—a show unhindered by the guiding political and religious institutions of the United States—it helps to have been a young white woman growing up a half century ago, as I did, inside the border of the Old Confederacy. In my Tidewater hometown of Hampton, Virginia, democratic hopes were abundant. The twenty years after World War II had seen American progressivism pry open the old Southern social order and force it to admit black Americans. Southern integrationists expected that another generation or two would banish Jim Crow forever, more or less as the scourge of polio had yielded to Salk’s vaccine. Such things were inevitable, after all, like the ever-rising prosperity guaranteed by American industry and empire.

What the progressives of my girlhood did not foresee was the postindustrial impoverishment of the working class; furthermore, even as the Republicans’ Southern Strategy captured the Old South, those same progressives failed to reckon with the lasting wages of America’s original sin. In time these two phenomena combined with ominous ramification. The crash of 2008 underscored the insecurity of the white working and middle classes, and in the context of this abiding insecurity, Trump’s slogan of “Make America Great Again” now clearly signals its real meaning: bring back white jobs, and with it white male power, to quell the threat of dark-skinned immigrants and the menace of black urban neighborhoods. Like the witch of Endor, Trump has the power to summon America’s undead, in the form of the white nationalists now relabeled the “alt-right.” Seizing the legacy of the new Southern Republicanism rooted in Richard Nixon’s cynical appeal to Dixiecrats, he has reanimated the race-hatred of the Old South.

The success of Trump’s dog-whistle appeal to race comes as no surprise to someone who observed firsthand the satisfactions that white Southerners took in segregation. In my 1950s childhood, Confederate statues and flags sanctified the landscape throughout the South. My nursery-school class marched, battle-flags clutched in our hands, to commemorate Confederate Memorial Day. My elementary school class watched Gone With The Wind during the Centennial. My Episcopalian parish featured a statue of a Confederate soldier in its graveyard, facing the town’s main street. My second-grade class excursion to Richmond included a devotional visit to Lee’s statue, where we learned that his boots had no spurs because the noble “General Lee would harm neither man nor beast.” At the time Virginia was fighting in vain to hold the line against miscegenation, its bitter defeat inscribed in the Supreme Court’s 1967 landmark ruling in Loving v. Virginia. Four decades after the last lynching in the state in 1926—which occurred after a white woman gave birth to a “mixed” baby and named a black man as the father—racial lines remained clear, and white women and black men knew all too well that they must not touch in public. Yet everyone also knew that the paler, blue-eyed blacks among us had come from precisely such unions.

Puritan America’s prurience had its analogue in my Tidewater town, and in every town from the Mason-Dixon line to the Rio Grande, where the threat of violence was so well-known to black residents that merely a look or a whisper brought fear. In Hampton, which had been an isolated farming and fishing village at the end of the Virginia Peninsula—a place where an emancipated “black” half-brother could buy land from his “white” kinsman—the deliberate undermining of Reconstruction after the Civil War had brought strict segregation, a segregation not eased by the presence of Northern missionaries who came to educate the former slaves. The later growth of the military presence there, the arrival of outsiders to work in the bases and the military-industrial complex around them, did not alter the way the twentieth-century South retained, for whites, the advantages of cheap labor, and the rituals of deference, afforded by the “peculiar institution.”

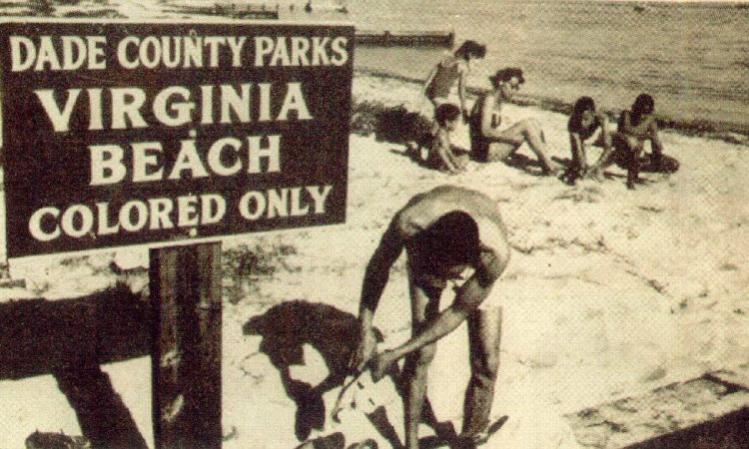

In my town, as in every town in Tidewater Virginia, many public buildings had “white” and “colored” water fountains, lest the races get too close when they drank. Some nearby hamlets posted signs: “Niggers Out By Sundown.” Schools were of course segregated, and one of my primary-school teachers informed her class of eight-year-olds that the Yankees wanted to bring black boys in to let them “get with” white girls. This panic at bodily intimacy extended to the water’s edge and even beyond. In the heat and humidity of the long Virginia summer, both races needed the relief of the salt water that bounded the marshy Peninsula. So each created a beach resort: Buckroe Beach, for whites, to the north along the edge of the Chesapeake Bay; and Bay Shore, to the south, for blacks.

Separating these two mirrored beach resorts—replete with hotels for each race—was a long chain-link fence that began in the sand dunes and stretched down into the water. A little white girl in her swimsuit could look through that fence and wonder, what was the point of dividing up a bay, when its waves washed over black and white alike? More than that, though, we knew that at night, when Cab Calloway or James Brown would come to Bay Shore Beach to perform, the white boys and men would jump the fence, following the allure regardless of Jim Crow. In the dark, then, the prurient pleasure of mixing; in daytime, the purity of segregation, affording Southern white men what they feared they might lose: the power to rule.

THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT—and several storms—erased the spectacle of apartheid from those Hampton beaches; but in the country at large, the Republican Party tacitly agreed to advance segregation by other racist means. This tacit agreement belies the exclamations of shock and horror that prevailed when Donald Trump captured the party’s nomination: Trump, the birther; the prurient flirt, who tells blacks how bad they are by telling them how bad they have it, and asks insolently for their votes, even as he energizes followers from among those whites who resent the presidency of a black man.

In March, House Speaker Paul Ryan responded to one of Donald Trump’s coy evasions. In one of his many flirtations with extremists, Trump had refused to disavow the endorsement of the Ku Klux Klan, and Ryan held a press conference to declare his desire to be “very clear about something.” The speaker continued:

[I]f a person wants to be the nominee of the Republican Party, there can be no evasion and no games, they must reject any group or cause that is built on bigotry. This party does not prey on people’s prejudices. We appeal to their highest ideals. This is the party of Lincoln.

In order to believe his own assertion, Ryan had to turn a blind eye to the eager willingness of his party’s top official, Reince Priebus, to ignore Trump’s repeated affirmations of bigotry. Ryan also had to turn away from the long history of the Republican Party’s “Southern Strategy” and its accommodation of segregationist Dixiecrats. Thanks to that bit of racial politics, there has in fact been plenty of room for bigotry in the party that claims the name of Abraham Lincoln. What that party can never justly claim is the moral vision of its founder, who acknowledged America’s original sin and saw its punishment in the form of “this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came.”

Though Donald Trump’s path to victory appears increasingly narrow as the election approaches, his ascendancy to the Republican nomination—boosted by his coded segregationist rhetoric—has left a mark on American politics. Even if he loses, he’s emboldened the dormant monster of white supremacy, in part by nurturing a pernicious lie that played to white resentment at the election of a black president. Assessing the significance of Trump’s appeal, John Cassidy, writing in The New Yorker, warned of a “long-term Trumpian movement —a nationalist, nativist, protectionist, and authoritarian movement that will forever be associated with him, but which also has the capacity to survive beyond him.” While Trump himself might lack the discipline of a serious candidate, Cassidy reasoned, another leader could arise in four or eight years to lead a movement like the Know Nothings of the 1840s or the America First Committee of the 1930s. Even a Republican like the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity’s* Avik Roy, interviewed in Vox, admits as much, asserting that “The Republican Party has lost its right to govern, because it is driven by white nationalism rather than a true commitment to equality for all Americans.”

The demise of a Republican Party based on racial animus is nothing to mourn. But Cassidy’s intuitions remain disturbing. Although a racist-fascist movement has never actually governed in the United States, we do have a long history of white supremacy, even white nationalism. Two recently published books describe moments in American history when these forces were in the ascendency, and they make for sobering reading today. American Slavery, American Freedom, by the late Edmund Morgan, explores the roots of modern racism in the bondage of colonial Virginia, when the new “science of race” provided a “natural” grounding for the “peculiar institution.” And the great historian Eric Foner’s Reconstruction: The Unfinished American Revolution tells the story of how the collusion of Northern and Southern interests led to the undoing of Reconstruction.

As Foner makes clear, and as Abraham Lincoln understood, no part of the country was innocent of the original sin of slavery—there was simply too much profit to be made, on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. Anyone who grew up in the segregated South of my childhood could not fail to recognize how advantageous for whites was the cheap labor provided by blacks, and how culturally formative was segregation’s insistence on the innate superiority of the white race. Things were different in the North, as I would discover as an adult—but not as different as most Northerners like to think.

At the Democratic Convention in July, Michelle Obama alluded to the sufferings of her ancestors in slavery, and to the Jim Crow laws and the hunting dogs of lynch mobs that began enforcing white supremacy after the defeat of Reconstruction:

That is the story of this country, the story that has brought us to this stage tonight, the story of generations of people who felt the lash of bondage, the shame of servitude, the sting of segregation, but who kept on striving and hoping and doing what needed to be done so that today, I wake up every morning in a house that was built by slaves, and I watch my daughters— two beautiful, intelligent, black young women—playing with their dogs on the White House lawn.

Yes, this nation has come a long way, but we still have a long way to go.

[*] An earlier version of this article referred to Avik Roy’s affilliation with the Manhattan Institute, which he left on June 1, 2016.