We are in the midst of the history wars. Is American history inextricable from the history of white supremacy? As the Rutgers historian Katherine Epstein points out in a recent essay for American Purpose, those on the Left who critique racial injustices in our nation’s past, like the New York Times Magazine’s 1619 Project, say yes, unwittingly adopting the interpretive frame shared by white supremacists themselves. Today’s conservatives, who reject this claim and emphasize America’s 1776-centered classical-liberal inheritance, have picked up where past left-wing historians left off.

Reckoning with these heated historical debates requires perspective—something that the study of history itself should grant us. To make sense of our fights over our past and its meaning, histories of our history wars might help. Enter Colin Woodard’s Union: The Struggle to Forge the Story of United States Nationhood.

Woodard sets out to explain “how and by whom the story of United States nationhood was created.” In telling his story about our story, Woodard, a journalist with the Portland Press Herald and a contributing editor at Politico, treats readers to a fast-paced, character-centered narrative instead of a textbook-style exposition. He persuasively argues at the outset that the roots of America’s history wars lie with our diversity. Building off his 2011 book, American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America, he explains that even after the successful close of the revolution, Americans weren’t, well, Americans:

These new states’ citizens didn’t think of themselves as ‘Americans,’ except in the sense that French, German, and Spanish people might have considered themselves ‘Europeans.’ If asked what country they were from, the soldiers who now occupied Yorktown would have said ‘Massachusetts’ or ‘Virginia,’ ‘Pennsylvania’ or ‘South Carolina.’

And even after these states came together to replace their loose association under the Articles of Confederation with a more robust national Constitution, they still lacked an organic sense of nationhood. As Woodard writes, “If a nation can be described as a people with a sense of common culture, history, and belonging, there were, in effect, a half dozen of them within these ‘United States.’” In the early nineteenth century, then, the United States “was in search of nationhood, a country in search of a story of its origins, identity, and purpose. It needed to find these things if it was to survive.”

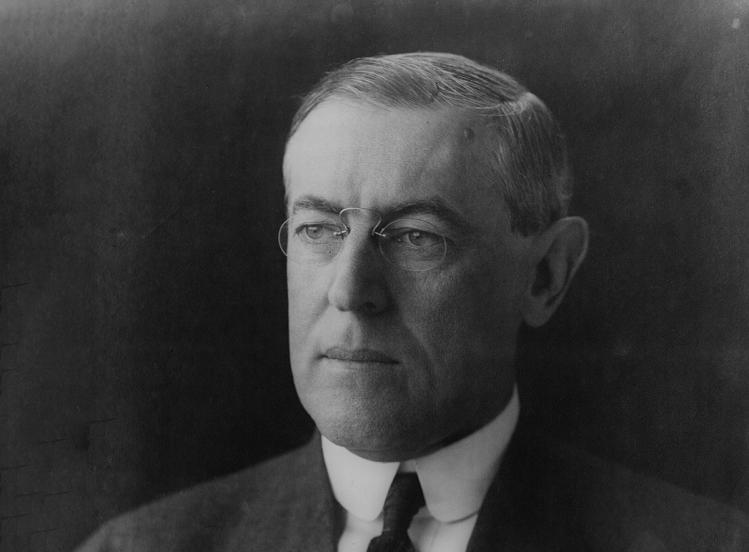

Into this void steps Woodard’s nineteenth- and early twentieth-century cast of characters, such as Frederick Douglass, historians like George Bancroft, and racist Southern intellectuals and statesmen like William Gilmore Simms and Woodrow Wilson. Some posited a vision of egalitarian, multiracial democracy grounded in the Declaration’s ideals; others put forth a similar vision, but with subtle racism lurking beneath the surface; while others pushed for, in Woodard’s characterization, a full-bore “ethnonationalist” American state and conception of the American past. Each of these perspectives had its own moment of prominence in American discourse, and Woodard explores both the personal lives and the theories of these figures to understand why their versions of the American narrative gained a supportive audience.

Take the character of George Bancroft. Woodard recounts Bancroft’s graduate studies in Germany. Having studied under Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Bancroft returned to the United States in 1822 with an understanding of history as “the unfolding of God’s plan for the world, and that plan was the progressive development of liberty, equality, and freedom.” Bancroft proceeded to write a multi-volume, award-winning series of books entitled, History of the United States, from the Discovery of the American Continent. There, he explained how the ideals of democratic liberty had passed down from the German Teutons, to the Anglo-Saxons, to New Englanders, and were now destined to span the entirety of the American continent. In the antebellum period, as American democracy forcefully expanded its continental reach and Europe remained mired in monarchy, readers greeted Bancroft’s vision of America with widespread acclaim. As Woodard writes, “His History was fast becoming the national narrative. And to the west, Bancroft was convinced he could see America’s sun rising high above the Earth.”

Yet Bancroft always papered over the existential threat that anti-Black racism and slavery posed to his providential nation. Woodard recounts a speech Bancroft delivered in Cleveland in 1860, in which he declared: “Our little domestic strifes are no more than momentary disturbances on the surface, easily settled among ourselves.” No wonder he was surprised when civil war broke out soon thereafter.

Bancroft was not up to the task of making sense of that war and its relation to American history. Frederick Douglass was. With a sharp focus on Douglass’s personal life—from his painful realization as a young boy that he was someone else’s property to his tireless advocacy against slavery throughout his adulthood—Woodard charts how Douglass sought to push his fellow Americans onto a similar path of realization, moral awakening, and then advocacy. With endless speaking tours, articles, and books, Douglass endeavored to wake Americans up to the racism in their nation’s past and present, and then propel them to bridge the gap between that reality and their professed ideals—ideals that pointed in egalitarian, universalist, and racially inclusive directions. Buoyed by powerful political allies like Abraham Lincoln, as well as the victory of the Union Army, Douglass’s vision for a morally perfecting America came to some amount of fruition in the bright morning sun of Reconstruction.

But backlash was swift. In perhaps the most compelling (and distressing) through line of Union, Woodard charts the deep roots of racist resistance to the American vision developed by Douglass and Lincoln. Bancroft elided American racism in his antebellum historiography, but Southern intellectuals like Simms placed it at the very heart of the nation’s character. Woodard charts how Simms’s novels and essays depicting ignorant and content Black slaves gained widespread praise throughout the South and informed the secessionist advocacy of Simms’s powerful political allies like James Henry Hammond. They also shaped the pro-slavery sermons of Joseph Wilson, “a Confederate nationalist of the first order,” and the father of one Thomas Woodrow Wilson.

Woodard writes how Wilson, a not-so-rigorous scholar before becoming president, incorporated white-nationalist themes into his writings, like his A History of the American People. His work there would be explicitly quoted in the racist, KKK-lauding 1915 blockbuster film The Birth of a Nation. Amidst his segregating of the federal government, President Wilson found time to preview it in the White House’s East Room prior to its release.

Woodard stitches these disparate narrative threads together to demonstrate how the American story has been shifting—and has been a source of contention—since the very start. Unfortunately, Woodard does not explain why he chose to devote all his focus to these few white and Black men (and they are all men). Women’s arguments regarding America’s past go unmentioned. This is a strange omission, given that the women’s suffrage movement was in full force during Woodard’s period of focus. Yet readers aren’t given a window into how the leaders of the suffrage movement conceived of American history. Their only mention comes in connection to Douglass’s support for their cause and Wilson’s distaste for it. Nor do we hear anything from the perspective of any European immigrants, millions of whom were streaming to America’s shores during that century and a half. Surely, they offered meaningful takes on their new home as they proceeded to shape its future—and with it, its conception of its past. Moreover, Woodard glosses over the mid-twentieth-century revolution in historiography—propelled by World War II, the civil-rights movement, and the Cold War—that placed the march of equal liberty at the core of our national self-understanding.

Still, as he jumps from character to character, Woodard underscores how Americans’ perceptions of themselves and their shared past have always been in flux. The past is permanent, but our collective understanding of it is not.

Having finished Union, then, readers would do well to keep Douglass’s wisdom in mind: “There is consolation in the thought that America is young.” So too are its internal battles over its history. And that history is contingent—full of twists and turns, progress and regress. Shaping it and telling it is up to each of us. As we engage in political battles and history wars, we must keep this perspective, and the responsibility that comes with it, at top of mind.

Union

The Struggle to Forge the Story of United States Nationhood

Colin Woodard

Viking

$30 | 432 pp.