In April 2015, Dan Price, the founder and CEO of a credit-card processing company, announced that he was raising the minimum salary at his firm to $70,000 a year, raising the incomes of more than half of his 120 employees. Price paid for it by reducing his own salary-plus-profits to $70,000 a year. What led him to do this? Price said that of all the social problems a business leader could do something about, inequality “seemed like a more worthy issue to go after.” Price’s announcement met with jubilation on the part of his employees, but not everyone was so pleased. Rush Limbaugh called it “pure, unadulterated socialism, which has never worked.” A business-school professor commented, “The sad thing is that Mr. Price probably thinks happy workers are productive workers. However, there’s just no evidence that this is true.”

Inequality has recently become a hot topic in the United States, so hot that two years ago Thomas Piketty’s technical, six-hundred-page Capital in the Twenty-First Century appeared on the New York Times bestseller list. Piketty’s central insight—now printed on T-shirts and bumper stickers—is that “r > g.” Translation: In the long run, the rate of return to capital is greater than the rate of economic growth; as a result, the proportion of total income and wealth that goes to the owners of capital will rise over time, while the proportion that goes to labor will decline. Unless we do something about it, economic inequality will gradually increase. The bulk of Piketty’s book is dedicated to proving this claim, but he does discuss a few possible solutions to the problem. His main policy proposal is a worldwide tax on wealth.

Anthony Atkinson’s Inequality: What Can Be Done? takes up where Piketty’s book leaves off. He largely ignores the long-term argument about the future of capitalism, demonstrates in detail how inequality has already risen in recent decades, and devotes most of his book to telling readers who already wish to reduce inequality the best ways to do so. The father of modern British inequality studies, Atkinson is Piketty’s mentor and a generation older. He writes that his intended audience is “the general reader with an interest in economics and politics,” and non-experts will always find his meaning clear. But since most of Atkinson’s discussion is about British history and policy, and since there’s a lot of detail, only the most wonkish of general readers in the United States are likely to get through this book.

The first hundred pages review the facts of inequality in recent decades and explain the various complexities that make inequality so difficult to discuss. (One of these complexities is the definition of income: Do we mean before-tax or after-tax income? Does it include capital gains? Food stamps?) The most widely recognized measure of economic inequality is the Gini coefficient, which is technically a measure of statistical dispersion—a way of summarizing the concentration of income. It is a number between zero and one, where zero means everyone has the same income, and one means that one person owns all the income. If we translate this number into a percentage, the United States and the United Kingdom are the most unequal industrialized nations, at about 36 percent (using after-tax incomes). Germany and France are in the middle at about 28 percent, while Sweden and Norway are the least unequal at about 23 percent. There has been a significant rise in inequality in the past forty years, which is what interests Atkinson most. In the 1970s, the Gini coefficient in both the United States and the United Kingdom was about 25 percent, just a bit higher than it is in Sweden and Norway today.

Since these percentages are abstractions, Atkinson adds the more concrete observation that to bring the United Kingdom back down to the level of income inequality it had when the Beatles were singing only by means of higher income taxes, you would need about a 50 percent increase in total income tax revenue. This would not only be impossible politically; it would also deaden the economy by reducing incentives. Thus, Atkinson argues that we can’t reduce inequality by fiscal policy alone. We must also change how incomes are generated.

ATKINSON DEVOTES MOST of the book to describing in some detail fourteen ways to reduce economic inequality. The first two proposals aim to alter the balance of power that currently exists in the economy, which is “weighted against consumers and workers.” First, because technological innovation is deeply shaped by the goals of those who fund the research behind it, Atkinson calls for a shift in the focus of government-funded research to encourage innovation that “increases the employability of workers and emphasizes the human dimension of service provision.” Second, other elements of public policy should “aim at a proper balance of power among stakeholders.” This includes antitrust policy that attends not only to increasing competition but to distributional effects also, a legal framework friendlier to labor unions, and the establishment of a Social and Economic Council, modeled on the one established in Germany after World War II and including both unions and employers’ organizations.

Atkinson’s third proposal calls on government to take various steps to reduce unemployment. For those who can’t find jobs in the private sector, Atkinson believes there should be a guarantee of public employment in service-sector jobs: childcare, preschool education, schools, youth services, health service, care for the elderly, Meals on Wheels, library services, and police-support activities. The fourth proposal calls for a “national pay policy” that would make sure the minimum wage was a living wage and establish a code of practice for pay above that minimum.

Atkinson wants to increase not just the income of ordinary citizens, but also their wealth. Toward this end, he proposes a national savings-bonds program to guarantee a positive real rate of interest on savings—with a maximum limit so that this advantage is not captured by the wealthy. He also endorses an idea that goes all the way back to Thomas Paine: on reaching the age of adulthood, every citizen would receive from the government a sizable “capital endowment” (with some limits on its use). Atkinson does not offer a specific number, but cites two recent proposals, one for £10,000 in the United Kingdom, another for $80,000 here. And to help pay for all this, Atkinson urges that each national government create a public-investment authority that would operate a sovereign-wealth fund consisting of investments in both businesses and real estate.

Atkinson’s final eight proposals turn to more traditional methods for altering the distribution of income. He recommends a more progressive personal-income tax, with a top marginal rate of 65 percent and a significant reduction in “tax expenditures” (the various ways governments encourage certain activities by reducing or eliminating the taxes they entail). He proposes a version of the U.S. Earned Income Tax Credit—payments to low-wage workers to supplement their income. Rather than taxing those who give an inheritance, Atkinson would have the government tax those who receive one: citizens would report inheritances and other gifts over a certain dollar amount as part of their annual income-tax filing, and these gifts would be added up over a lifetime, with higher lifetime receipts being taxed at higher rates. Such a tax, aimed at the living recipient of an inheritance, could not easily be described (and opposed) as a “death tax.” Atkinson would also like to see “a renewal of social insurance, raising the level of benefits and extending their coverage.” The central issue here is unemployment insurance, which has receded in the United States over the past quarter century. In 1985, 35 percent of unemployed Americans received benefits; twenty years later only 19 percent did. In Germany, by contrast, more than 75 percent of the unemployed receive benefits.

Atkinson is generally opposed to means-testing, which limits government subsidies to those in financial need. For example, he proposes a substantial per-child benefit to be paid annually and taxed as income so as to help the poor more than the rich, but he wants every family to receive the benefit regardless of income. Atkinson offers two major reasons for his opposition to means-testing. The first is that it functions as a disincentive to work. If you’re receiving some sort of means-tested assistance and begin to work and earn more, your income goes up by the amount earned but down by the loss in benefits. In effect, the poor face a very high marginal tax rate as their incomes rise, at times as high as 70 percent. Say you’re a part-time worker receiving government assistance and you’re considering taking up your boss’s offer to work one more day a week at $10 per hour. Your gross income would go up by $80, but the 70 percent tax rate—a combination of ordinary income and payroll taxes plus the loss of government subsidies—would mean that you would end up taking home only another $24 for the additional day of work, which is not much of an incentive. This creates a kind of poverty trap. Atkinson’s second argument against means-testing is that many who are entitled to benefits do not collect them, but would if those benefits went to all citizens. To give one example, the Earned Income Tax Credit distributes an average of $2,400 to each of 28 million low-wage U.S. citizens each year, but nearly six million others who qualify for the credits do not receive them. A third argument, not mentioned by Atkinson, is that benefit programs are less politically vulnerable when all citizens receive the benefit. Social Security and Medicare, which benefit everyone of a certain age, are far safer than Medicaid, which benefits only the poor.

Atkinson’s final proposal addresses global inequality. He wants wealthy nations to increase their target for development assistance to poor countries from the current level—seven-tenths of 1 percent of GDP—to 1 percent. Although Norway and Sweden already meet the higher goal, most nations fall short of the lower goal. The United States contributes more than any other nation in absolute terms, but this dollar amount represents the lowest percentage of GDP among industrialized nations—less than two-tenths of 1 percent.

The last section of Inequality addresses the question “Can it be done?” Atkinson begins by asking whether his proposals would reduce economic growth (“the size of the cake”). He concludes that it might or might not. (His argument here would have been strengthened by reference to the work of American economic historian Peter Lindert, whose research, ranging over many countries and decades, has demonstrated that social-welfare spending has not of itself reduced economic growth.) Atkinson then asks whether globalization prevents steps to reduce inequality within particular countries. He points out that in a prior period of advancing globalization before World War I, industrializing nations took great steps toward Social Security legislation. And, he argues, many of the globalizing pressures on domestic economies are not simply elements of nature but are produced by international trade agreements.

This leaves one more question: Can we afford it? Atkinson drills down into the figures to show that, in the United Kingdom at least, the answer is yes—and at a much lower price tag than one might guess.

‘INEQUALITY’ IS A REAL accomplishment. It represents the first comprehensive, realistic, and detailed proposal for countering growing economic inequality—and it’s done not by some energetic graduate student but by a seasoned economist who’s been working on these issues for more than forty years.

Still, Atkinson’s approach has significant limitations: in choosing to write about how to reduce inequality if that’s what you want to do, the author largely ignores political issues that would have to be addressed before his program could be implemented. Not everyone believes that inequality is a problem. (Whenever one politician mentions inequality, another can be counted on to cry, “class warfare!”) And some who do regard inequality as a problem believe the problem can be solved only by revolution, not reform. Readers on the far left will dismiss Atkinson’s book for not condemning the whole global capitalist system, for trying to solve a deeply structural problem by changes at the surface. Readers on the right will judge it to be simply a “big government” solution that will violate the rights of the prosperous, reduce economic growth, and distort economic incentives for nearly everyone. Particularly in the United States, there are more of the latter than the former these days, the success of Sanders notwithstanding. And so one must confront the question of whether it might be wiser to address economic injustice by focusing on poverty rather than inequality. After all, everyone believes that poverty is a problem.

In the long history of religious thought on economic life, almost nothing was said about inequality from the time of the Hebrew prophets to the modern era. There was always an intense concern about justice, but the focus of that concern was on need: God had given the world to humanity so that the needs of all would be met. The fathers of the church were adamant in their insistence that the wealthy share what they had with the poor, but they did not appeal to the concept of equality. As long as the needs of all were met, there was no presumption that it would be wrong for the wealthy to have more than everyone else. This began to change as the church, along with secular political theorists and social scientists, began to appreciate the importance of participation as a morally critical dimension of human flourishing. Since the nineteenth century, Catholic social teaching has discouraged extremes of economic inequality, which disenfranchise the poor in so many ways. Inequality, it turns out, is about more than who has the most stuff.

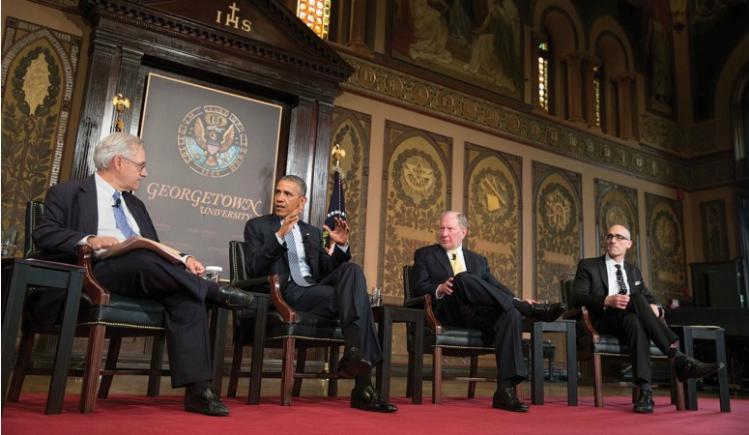

Still, given the political situation in the United States today, it makes more sense to focus on poverty, even if one’s goal is also to reduce inequality. This very conviction led to the Catholic-Evangelical Summit on Overcoming Poverty held in May 2015 at Georgetown University. The event was organized by the religious leaders behind the Circle of Protection, which had campaigned to protect federal programs for the poor from the cuts of the Congressional “sequester.” The organizers focused not only on what Catholics and Evangelicals can agree on when it comes to poverty—which is a lot—but more narrowly on policies and programs that have some hope of implementation in the current political climate. Participants discussed various ways to get poverty, particularly child poverty, onto the agenda of presidential candidates. But even politicians who care about poverty have in recent years been advised by their political strategists not to mention the topic. Even if everyone believes poverty is a problem, not everyone regards the problem as a high priority—partly because low-income citizens are less likely to vote. During campaign season, candidates of both parties tend to focus instead on the middle class. And even when they lament that the middle class is disappearing, they sometimes talk about it as if it included everyone who isn’t either a millionaire or homeless. The poor too often go unmentioned. This is why Christians concerned about economic justice must do whatever they can to make poverty an issue before and after elections. One of the Evangelical leaders at the summit in May described a discussion in the White House that eventually persuaded Barack Obama to sign on to the Circle of Protection. A Catholic bishop reminded the president that the Bible does not say, “Whatever you do to the middle class you do unto me.”