The Writers Guild of America —the labor union of Hollywood’s screenwriters—recently voted to strike in part because TV and film studios wouldn’t negotiate limits on the use of AI to write scripts. Reducing a room full of writers to one “writer,” whose job would no longer be to actually write but to prompt and edit the output of an AI program like ChatGPT, would of course save studios a lot of money. But that money would be saved at the expense of both the humans replaced by AI and the humans whose entertainment would be created by it. If audiences are already complaining that shows and movies are too formulaic and repetitive, how much angrier would they be if Hollywood produced only “content” constructed out of the rearranged pieces of already existing shows and movies? The writers’ strike can therefore be seen as not only a move to protect jobs in Hollywood, but, in a sense, to protect Hollywood itself.

At the same time, teachers at schools and universities are scrambling to adapt to the threat of ChatGPT and other increasingly ubiquitous and difficult-to-detect “generative AI” programs. It’s unclear how to evaluate homework when teachers can no longer know for certain whether students are the real authors of their work. On the traditionalist side of the debate, there are calls to fight AI by turning to oral exams and in-class, on-paper writing assignments. On the more progressive side, there are calls to embrace it by explicitly asking students to use ChatGPT as part of the writing process. Students would learn how best to prompt ChatGPT to write essays that they would then assess and edit. If the AI we use to detect plagiarism cannot keep up with the AI that plagiarizes, then embracing AI seems to many administrators and instructors a better solution than waging a hopeless war against it. Then again, if Hollywood writers would rather strike than work with AI, then asking students to work with it might be regarded as preparing them for jobs no one really wants in a world no one really wants.

Do we really have no choice beyond this binary: to either fight AI or embrace it? If fighting AI seems self-defeating and embracing it self-destructive, then why are we letting tech companies continue to develop ever more powerful AI programs? And if even the CEOs of these tech companies are worried about the potential threat to humanity, then why should we continue to pursue AI at all? Of course, it could be argued that the fears concerning AI are either the result of misunderstanding or mere hype designed to make AI seem more powerful than it really is. Is AI really a threat to humanity? Or is it just a complex—and scary-seeming—tool that, like any other tool, is designed to make life a little bit easier?

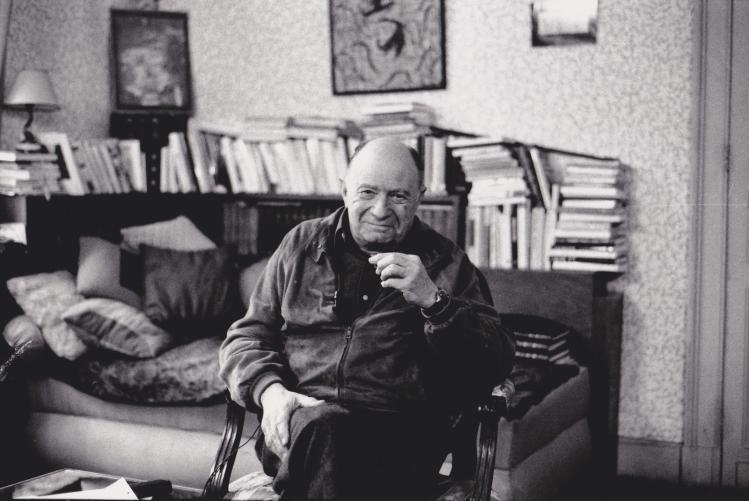

A compelling answer to these questions comes in the work of an intellectual who died long before ChatGPT, or even AI, came into existence. Jacques Ellul (1912–1994) was a French philosopher, sociologist, theologian, and professor who authored more than fifty books covering topics such as politics, propaganda, violence, and Christianity. In a recent book about the life and work of Ellul, Jacob E. Van Vleet and Jacob Marques Rollison argue that Ellul’s writings can be separated into two strands: sociological and theological. Alternatively, these two strands can be labelled as pessimistic and optimistic, for while his sociological texts have led academics to dismiss Ellul as a dystopian fatalist, his largely overlooked theological texts instead center on hope and the need for political engagement. Most importantly for our purposes, Ellul’s work in the 1950s focused on the growing concern about the relationship between technology and society.

To be more precise, he wrote about the relationship between “technique” and society. Owing to the complications of trying to translate French into English, “technique,” a central concept in Ellul’s work, has been rendered sometimes accurately, and sometimes misleadingly, as “technology.” In fact, the difficulty differentiating the concept of “technique” from “technology” could itself be seen as the result of precisely the kind of problem Ellul was trying to illuminate in his work.

According to Ellul, we are living in a technological world not only because tech is everywhere but because we are living in a world of technique. By “technique,” Ellul referred broadly to the way we accomplish tasks. In the opening of his 1954 work The Technological Society, Ellul defined “technique” as “the totality of methods rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency (for a given stage of development) in every field of human activity.” Painters use different techniques for painting, chefs have techniques for cooking, comedians have techniques for telling jokes, and so on. But an increasing focus on how things are done rather than why they are done, Ellul argued, means that the idea of having different techniques for different goals is giving way. Instead, optimizers simply try to figure out how every task can be accomplished in the most efficient way possible. As Ellul put it, “The technological phenomenon is the preoccupation of the great majority the men of our day to seek out in all things the absolutely most efficient method.”

This concerned Ellul because efficiency is pursued not in accordance with our values, but rather because efficiency has itself become the value by which everything is judged. In other words, we judge whether something is good based on how efficient it is, because good and bad have come to mean nothing other than efficient and inefficient. “Good” workers—for example, Hollywood screenwriters—are now more likely to be judged by how efficiently they produce profit-making work than by the quality—the aesthetic merit in this case—of that work.

Machines, according to Ellul, are the ideal embodiment of technique because they are designed for efficiency: they do nothing but perform the desired activity in the shortest possible time with the least possible effort. According to the ideal of technique, the activity itself—its human meaning and rationale, the tradition behind it—does not matter. What matters is that a machine can seemingly perform any activity in the most efficient way possible. In a society driven by technique, which has thrown over all other values, the most important activity a machine can perform becomes the production of more and better machines. Factories are thus often made up of machines that make little else but parts to make more machines. We come to want machines to do every activity, and we come to see every activity as something a machine could do better—that is, more efficiently—than any human being.

In theory, the more chores machines can complete for humanity, the more we humans should be free from toil and able to use our time for more meaningful activities. In practice, however, as Ellul pointed out, humans are not liberated by machines; instead of machines working for us, we often find that we are forced to work for machines. As Ellul writes in 1977’s The Technological System:

In reality, for most workers, technological growth brings harder and more exhausting work (speeds, for instance, demanded not by the capitalist but by technology and the service owed to the machine). We are intoxicated with the idea of leisure and universal automation. But for a long time, we will be stuck with work, we will be wasted and alienated. Alienation, though, is no longer capitalistic, it is now technological.

We have been subordinated to machines not because, as in science-fiction dystopias, they have risen up and taken over the world, but for a much more mundane reason: machines only work so long as humans keep them working. Machines never function as smoothly as promised, since they are made up of complicated moving parts, which frequently require human intervention to prevent them from malfunctioning, wearing out, and breaking down.

The more tasks that are taken over by machines, the more vital it becomes that we are able to keep machines functioning well. To live surrounded by machines, one has to learn how to take care of them, and so education has increasingly become focused on how to build machines, how to maintain machines, and how to repair machines. It would come as no surprise to Ellul that education focused on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (the so-called “STEM” fields) has come to replace traditional education focused on the humanities. Learning about anything other than STEM has come to be seen as antiquated, belonging to a world we no longer inhabit, preparing students for jobs that no longer exist.

Once we reduce all education to STEM, according to Ellul, we lose the ability to make any value judgments about machines other than those to do with their efficiency. Worse yet, we tend to not see this as a danger because we do not think machines should be judged except based on their efficiency. Since we see machines as mere means to human ends, we think human ends are what should be judged, not the means we use to achieve those ends. Thus we find calls to develop, for example, “Drones for Good” as if the intentions of the drone operators alone determine whether drone technology is “good.” Such sentiment fails to recognize the way merely operating a drone, like holding a gun, is likely to alter how we see the world and thus reshape our intentions.

Tools, it is repeatedly said, are not good or evil; only humans and human actions are. What matters is how people use tools, not the tools themselves. But if we value efficiency over any other goals and if we use machines to create more and better machines, then machines are not mere means, they are ends in themselves. This is why Ellul argued that machines have become autonomous while humans have lost our autonomy. The progress of technology is seen as inevitable and unquestionable because it is equated with human progress. As Ellul put it, “Each [new] technological element is first adapted to the technological system, and it is in respect to this system that the element has its true functionality, far more so than in respect to a human need or social order.”

Machines have become so integral to human life that we cannot even make decisions for ourselves without the intervention of machines. Scientific knowledge depends on experiments and so scientific knowledge can only develop in accordance with the development of experimental equipment. Mathematical knowledge depends on calculations and so mathematical knowledge can only develop in accordance with the development of calculating devices. Military power depends on weapons and intelligence and so military power depends upon the development of military technology. Consequently, decision-making based on the knowledge produced in these areas depends on machines. Ellul argued that politicians cannot intervene in technological development without putting the security of the state at risk, and so political power no longer rests with politicians, but with technicians.

All the theorists, politicians, partisans, and philosophers agree on a simple view: The state decides, technology obeys. And even more, that is how it must be, it is the true recourse against technology. In contrast, however, we have to ask who in the state intervenes, and how the state intervenes, i.e., how a decision is reached and by whom in reality, not in the idealist version. We then learn that technicians are at the origin of political decisions.

Only those who best understand technology have real political power in a technological society. Does this technological domination of politics imply “the emergence of a technocracy”? Perhaps surprisingly, Ellul answers no:

Absolutely not in the sense of a political power directly exercised by technicians, and not in the sense of technicians’ desire to exercise power. The latter aspect is practically without interest. There are very few technicians who wish to have political power.

Technicians are far more interested in money than power. But politicians are left incapable of judging technological progress without seeking the advice of people with technological understanding, and so politicians cannot regulate tech companies without the help of the very tech companies they are trying to regulate. We’ve seen this dynamic play out time and again in Washington: Congress holds hearings about excesses and abuses in the tech industry, but members of Congress demonstrate a poor grasp of the issues involved and the prospects for regulation come to depend entirely on industry insiders and lobbyists.

Consequently, according to Ellul, technological progress has resulted in the death of democracy. But this does not mean that technocracy, in the sense of rule by experts, has risen up to take its place. Instead, Ellul argued that not even the experts are in control. There is a power vacuum in technological societies, with neither a democracy nor a technocracy in place. We try to fill this power vacuum with more and more bureaucracy, and so it might seem like we are living in a technocracy. But, in reality, our political decisions are merely carried out by humans trying their best to act like machines while making decisions based on information gathered by machines. As Ellul put it,

[P]eople see a technician sitting in the government minister’s chair. But under the influence of technology, it is the entire state that is modified. One can say that there will soon be no more (and indeed less and less) political power (with all its contents: ideology, authority, the power of man over man, etc.). We are watching the birth of a new technological state, which is anything but a technocracy; this new state has chiefly technological functions, a technological organization, and a rationalized system of decision-making.

Ellul presents us with the prospect of a world where ends don’t justify means, but means justify ends—where we don’t rely on values to debate and determine societal goals, but let the development of new tools determine what tasks are worth achieving. With this understanding of our technological world, we can begin to answer the questions I posed at the outset. From Ellul’s viewpoint, it is no surprise that we are today pursuing AI as a potential solution to social problems, while at the same time worrying about a host of new, perhaps even worse problems that it may cause. It is a perfectly predictable outcome of our single-minded focus on technique and efficiency.

Take our confusion about what precisely AI is—whether it is able to actually understand what it creates or if it merely appears to understand. From an Ellulian perspective, this can be construed as the result of our inability to determine any longer whether we ourselves understand what we create or merely appear to understand. By reducing our projects to series of tasks that can be achieved by either humans or machines, we cannot help but compare ourselves to machines. Valuing efficiency above all else, we come to see humanity as an inferior kind of machine. At the same time, we have begun defining humanity solely in terms of what humans can do and machines cannot—thinking, feeling, and creating. But since we see even these achievements as mere tasks, the line between humans and machines has become increasingly blurry: tasks that only humans can do have come to be seen as tasks that only humans can do for now.

From Ellul’s perspective, the question of whether machines can think, feel, or create is not what we should worry about. The reduction of human actions to mere tasks means that whether or not machines are becoming more like humans, humans are becoming more like machines. To see thinking, feeling, and creating as tasks is to see such activities as means to ends rather than as ends in themselves. If we adopt this instrumentalist perspective, we have already conceded that machines are our equals. Thinking, on this view, can only be thinking about how to achieve some task, and so, of course, machines can think because they can process and execute commands. Likewise, machines can feel and create because these human activities have similarly been reduced to instrumental processes defined by their efficiencies and outputs, which machines can replicate and even, increasingly, exceed.

For Ellul, then, the challenge posed to humanity’s value by technique and its “absolute,” efficiency-obsessed form of rationality has become all-important. He writes:

The computer faces us squarely with the contradiction already announced throughout the technological movement and brought to its complete rigor—between the rational (problems posed because of the computer and the answers given) and the irrational (human attitudes and tendencies). The computer glaringly exposes anything irrational in a human decision, showing that a choice considered reasonable is actually emotional. It does not allow that this is translation into an absolute rationality; but plainly, this conflict introduces man into a cultural universe that is different from anything he has ever known before. Man’s central, his—I might say—metaphysical problem is no longer the existence of God and his own existence in terms of that sacred mystery. The problem is now the conflict between that absolute rationality and what has hitherto constituted his person. That is the pivot of all present-day reflection, and, for a long time, it will remain the only philosophical issue.

In a world governed by absolute rationality of this kind, it should come as no surprise that students see generative AI programs like ChatGPT as a tool they should take advantage of. It is less efficient to write a paper oneself than to have a computer do the writing for you, just as writing by hand is less efficient than typing. Furthermore, since writing papers is a means to getting a degree, getting a degree a means to getting a job, and getting a job a means to making money, then students will likely see using ChatGPT in school as the most efficient way to prepare for their future jobs, just as their future employer will see it as a more efficient way to make money. That ChatGPT may be generating what seem like academic papers but are instead merely words and sentences strung together based on statistical probabilities is not important, since the student does not see academic papers as important in themselves. Valuing efficiency above all else means that what matters is entirely extrinsic—that a given task was completed—and not intrinsic—whether the task was completed well. If it was done quickly and easily then, from the perspective of technique, the task was completed well.

From Ellul’s point of view, then, we should be less concerned about the threat of AI than about the far more fundamental threat of technique. So long as we view human activity as a mere series of tasks and we value, above all else, the completion of these tasks in the most efficient way possible, we will continue to see AI as both inevitable and desirable. We will become increasingly dependent upon AI while also increasingly unable to understand it. But these drawbacks, if they are considered at all, will be construed as costs far outweighed by the benefits AI. The question, then, of whether we can make AI align with human values ignores the fact that human values, as they are constituted today, have given rise to AI in the first place. The question we should be asking is whether we can make “human values” align with our humanity.

Ellul is often misread as a dystopian thinker who claimed that we are powerless to stop technology because of “technological determinism,” which has made human freedom a thing of the past. For this reason, he has been criticized by philosophers of technology like Andrew Feenberg for having supposedly neglected the fact that technological progress is driven by human decisions. But Ellul’s pessimism derives instead precisely from his awareness that human decisions are driving technological progress. Ellul didn’t suggest it is not possible to make different decisions, but rather challenged us to ask ourselves what it would take for us to do so. If valuing efficiency has created a world where technological progress seems inevitable while human progress seems to be in jeopardy, will we recognize the inhuman world we have created and choose to embrace different, more human values?

Ellul thought there were three ways we could become free from the world that technique has created. First, there could be a nuclear war that would either end the world altogether, or at least end the world’s dependence on technology. Second, there could be divine intervention from God. Third, we could wake up and see the reality we have created for what it is. We could come to see that we are not being liberated by new technologies, nor made happier, and start to create a new, better reality concerned more with embracing what it means to be human rather than with the perceived benefits of reducing humans to mere means.

It was the possibility of the third option that motivated Ellul to write rather than to resign himself to despair. And it is the possibility of the third option that should motivate us today to read Ellul rather than give up and ask ChatGPT to summarize Ellul for us.