In “Commitment to Marriage,” an open letter issued before last month’s Extraordinary Synod on the Family, prominent social conservatives urged the bishops to take a variety of steps to strengthen traditional marriage.

The letter asked the synod to “support efforts to preserve what is right and just in existing marriage laws, to resist any changes to those laws that would further weaken the institution, and to restore legal provisions that protect marriage as a conjugal union of one man and one woman, entered into with an openness to the gift of children, and lived faithfully and permanently as the foundation of the natural family.”

It’s clear that the authors consider gay marriage and polygamy to be among the changes to be resisted. But what legal provisions, exactly, should be restored? As I pondered this question, I realized even more sharply the limits of lawmaking. It’s not enough for a law to have a good purpose in order to be a good law. It also has to achieve that purpose by means that are fair, and that don’t impose unacceptable ancillary burdens.

Two hundred years ago, Anglo-American law assiduously upheld the vision of marriage the letter advocates. But key legal buttresses were dismantled piece by piece, because they inflicted other moral costs—particularly on women and children—that were too high to pay. Here are five examples.

Married women’s property laws. In the Christian view of marriage, a husband and wife lose their distinct identities and become one person. In the Anglo-American common-law tradition, that person was the husband. A married woman could not own property, enter into contracts, write a will, or earn a salary. In 1867, the Illinois Supreme Court baldly stated the pragmatic justification for this scheme: “It is simply impossible that a married woman should be able to control and enjoy her property as if she were sole, without practically leaving her at liberty to annul the marriage.” Nonetheless, over several decades beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, American state legislatures began to take steps that allowed a married woman to retain some legal and financial independence.

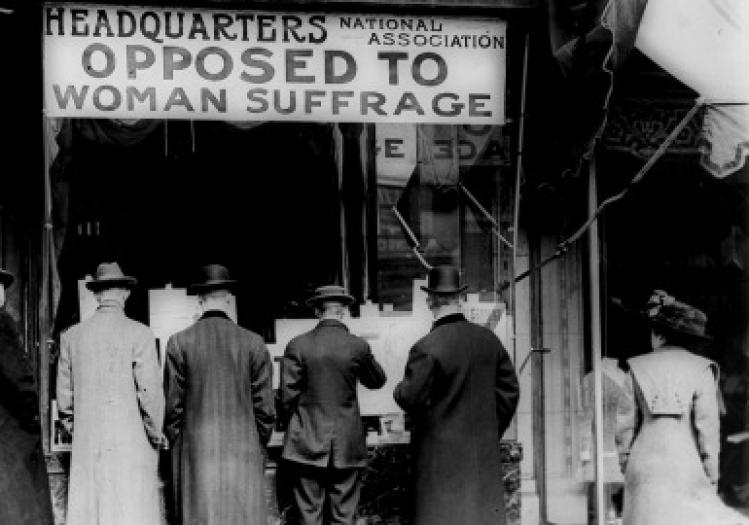

Women’s suffrage. Opponents argued that women’s suffrage would disrupt the equilibrium between the sexes. A pamphlet produced by the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage in 1910 claimed that giving women the vote “means competition of women with men instead of cooperation.” It alleged that “80 percent of the women eligible to vote are married and can only double or annul their husband’s votes.” When women gained the vote in 1920, they acquired basic political equality—and political independence from their husbands.

The Uniform Parentage Act. In the common-law tradition, illegitimate children had no right to support from their fathers, no right to use the paternal name, and no right of inheritance. Such laws reinforced the tight connection between marriage and childbearing. But they inflicted tremendous harm on children who were not responsible for the circumstances of their birth. In the late 1960s, the U.S. Supreme Court began striking down laws disadvantaging illegitimate children on the grounds that such provisions deprived them of the equal protection of law. Most states have now enacted some version of the Uniform Parentage Act, which gives children with unmarried parents the same rights as those whose mother and father are married.

Decriminalizing adultery and fornication. Until the mid-twentieth century, most states had laws against extramarital sex. They aimed to reinforce traditional sexual morality, to ensure that men were responsible for raising only their own children, and to deter the propagation of children out of wedlock. In the 1960s, many states began decriminalizing these acts, while others left the statutes on the books but did not enforce them. People not only wondered whether enforcing such laws was the best use of governmental resources, they also feared the enormous power they gave the government to intrude into the most intimate aspects of their lives.

No-fault divorce laws. In the late 1960s, most states moved from permitting divorce only on certain grounds (adultery or mental cruelty) to no-fault divorce. It is this shift that the authors of “Commitment to Marriage” would most like to reverse. But at what cost? States moved away from fault-based divorce in part because there was widespread perjury, including collusion between the parties, in determining “fault.” Some recent research suggests that domestic violence and female suicide are lower in states with no-fault divorce. Moreover, fault-based divorce can’t make married couples maintain a home together—it can only keep them from remarrying.

The law isn’t magic. It can’t undo major shifts in culture. Instead of figuring out how to pressure more young people to get married and stay married, it might be wise to spend some more time asking them why they think the institution of marriage no longer meets their needs.