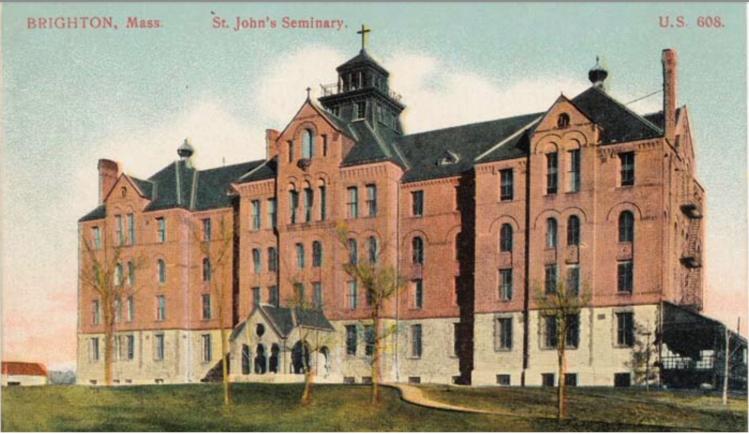

The story begins on a bright afternoon many years ago, one I remember as though I’d seen it. (This is natural enough in a family like ours, with its canon of approved stories. They are told in the manner of repertory theater: hang around long enough and you’ll hear them all.) Imagine the trees tinged with red, a sky so clear it seems contrived, the high blue heaven of tourist brochures. It is the first resplendent day of a New England fall, and Ma’s new husband—my father, Ted—is driving from Grantham to Brighton, his hand on her thigh. They are dressed for a wedding or a funeral: she in Sunday hat and gloves, he grudgingly coaxed into a suit. In the back seat is a battered footlocker from his Navy days, packed with the few possessions a junior seminarian is allowed. Squeezed in beside it is Art, fourteen years old, staring out at a scene that will shape the rest of his life: the headquarters of the Boston Archdiocese and its famous seminary, St. John’s.

The decision to come here had been his alone. From the age of ten he’d served as an altar boy. Two mornings a week he’d met Fr. Cronin in the vestry at St. Dymphna’s, helped him into his alb and chasuble. At the altar Art genuflected, lit candles, carried cruets. At the consecration he rang the bells. The sound never failed to send him soaring, a feeling that was nearly indescribable: a sweet exhilaration, a spreading warmth. In those moments he’d sensed a transformation occurring, before him and inside him. Bread and wine into the Body and Blood. An ordinary boy into something else.

In the confessional Fr. Cronin posed the question. Have you ever considered it? They discussed at some length what a vocation felt like, how you could ever be sure. Certainty will come later, the priest promised. And one Sunday after Mass, he invited Ma to the rectory for a chat.

Now, washed and waxed for the occasion, Ted’s car passed through the stone gates. A few others were already parked behind the dormitory, a cavernous brick building perched atop a hill. Ted hefted the trunk to his shoulder and with much grumbling hauled it up three flights of stairs, down a long corridor to the cell Art would share with a boy named Ray Cousins.

Like all others on the third floor, Art’s cell was small and square. In it were two narrow beds, two wooden desks. The floors were bare; metal blinds hung at the one window. There were no rugs—a fact my mother emphasizes in the telling—and no curtains. No trace, anywhere, of anything soft.

Ted set down the trunk. Ma was uncharacteristically silent, her eyes welling. It was the moment Art had dreaded for months.

“I’ll be fine,” he said, embracing her. “I’ll write you.” Briefly he shook Ted’s hand.

I should say a few words about that campus, which figures so prominently in the life and ministry of my brother. How those buildings came to be is a story in itself. For the nearly forty years that William Cardinal O’Connell ran the archdiocese, Boston was the capital of Catholic America, and in his eyes it deserved a facciata as grand as the Vatican. “Little Rome,” the local papers called it, the hills of Brighton dotted with monuments: the seminary’s neoclassic library and exquisite chapel, the elegant palazzo where the cardinal slept and the ostentatious mausoleum where he sleeps now. At the entrance of each building was carved the cardinal’s own motto, Vigor in Arduis.

Strength Amid Difficulties.

It was, in every way, the house O’Connell had built.

Art was barely a teenager when he arrived there, and for twelve years it was—not his home, exactly, but as close to one as a seminarian was allowed. Later I would visit him there. Together we walked its landscaped hills, its winding footpaths. Art showed me a shady grove of cedars that hid a secret: a round swimming pool, long drained, its cement cracked. The pool was twelve feet across and five feet deep. Cardinal O’Connell had ordered it dug for the summertime refreshment of his dogs, two black poodles that, like the seminarians in their black cassocks, suffered from the heat.

In minor seminary, order was paramount. The boys lived according to an ancient template, a sixth-century invention of St. Benedict known as the Rule.

The Rule governed the boys’ movements. The seminary day was punctuated by bells. There were bells for sleeping and waking and morning Mass, for meals and study and sports. Six classes a day, each an hour. Each opened and closed with a prayer.

At first bell the boys rose and dressed. An upperclassman handpicked by the rector made his way down each corridor, singing out the morning greeting: Benedicamus Domino. The boys sang in answer: Deo gratias.

The day’s first class was Latin. The teacher, Fr. Fleury, had studied in Rome. He was young and fair-haired and wished himself elsewhere—among the ruins at Ostia Antica; kneeling before the Sacrament at Santa Maria Maggiore; walking along the Tiber, breviary in hand. In a few short years the Latin Mass would be abandoned, but at St. John’s the curriculum would not change. Why learn Latin if the Mass was said in English? If the boys wondered, they gave no sign. They declined and conjugated and asked no questions. Fr. Fleury corrected them rigorously.

In nomine Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti.

A bell rang.

The boys processed to algebra, then history. The noon bell called them to chapel. In silence they walked to the refectory for lunch. A hot meal always, meat bathed in slick gravy—unappetizing fare, and yet they’d have killed for more of it; the invisible cooks, by ignorance or design, misjudged the hunger of growing boys. The priests sat up front at a long table, the rector at the center. At his elbow was a brass bell. If he rang the bell after the blessing, talking was forbidden. A seminarian would read aloud from Scripture. A hundred boys chewed and swallowed.

A bell rang.

English came next; then history, biology. A bell rang for afternoon rec. The gymnasium had tall mullioned windows, as the dead cardinal had ordered; they’d been covered in chicken wire to protect the fine glass. The boys suited up for basketball, a game Art had once avoided. (In Grantham it was a sport for tough boys. A Morrison or a Pawlowski might take out your eye.) But like everything at seminary, sport was mandatory; and Art was no longer the smallest or the shyest. Day after day the boys raced across the court, a crest painted at its center: Seminarium Sancti Joannis Bostoniense 1884.

A bell rang.

The boys showered and dressed, for dinner, rosary, spiritual reading. At eight o’clock came the Grand Silence. Until breakfast the next morning, talking was forbidden. Not a word would be spoken in the corridors.

The routine was fixed; it deviated for no one. Like those before him—more majorum—Art lived by the Rule.

He took to this new life with great enthusiasm, a sunflower turning its face to the sky. He loved the orderly days, the mornings in chapel. The silence nourished him; his soul expanded to fill it. Every moment of the day became a prayer. The buildings themselves thrilled him, their high vaulted ceilings—to draw the eye upward, said Fr. Dowd; the mind closer to God.

Fr. Dowd taught the boys music. He was the youngest of the faculty, a brand-new priest, only eight years older than the senior boys. The other priests treated pupils with a certain disregard, knowing that half would leave before graduation, that a scant 10 percent would eventually be ordained. But Fr. Dowd was not dismissive. He was known to have favorites. Those boys who sang out joyfully, who were not struck deaf when singing harmony: his work was made bearable by such pupils, the Arthur Breens and Gary Moriconis who could still hit the high notes. That first year, unspoiled by puberty, Art sang like an angel. In class, after his solo, Fr. Dowd had said as much. “What I would give for a dozen Breens,” he told the boys, his eyes misting with pleasure. Arthur Breen could sing anything. His voice was God’s gift.

“Such a pity,” Fr. Dowd told the class, “that it has to change.”

He launched, then, into a history lesson. Centuries ago, a voice like Arthur Breen’s would have been preserved by castration. The castrati were the superstars of their day, the primi uomi of early opera. They sang with otherworldly range and power, the darlings of popes, cardinals, and kings.

Listening, Art had blushed scarlet. From that day onward he avoided Fr. Dowd’s confessional, a choice easily justified: Fr. Dowd’s line was always the longest, his favorite boys —Ray Cousins, Gary Moriconi—at the head of the line.

Of Art’s teachers, Fr. Fleury was the most inspiring. He spoke often of his travels to Rome. The splendors of Vatican City he called our patrimony. Every Catholic ought to visit as often as possible. To his pupils it was a stunning admonition; in their working-class neighborhoods, Rome might have been Neptune. Art listened in fascination. His Latin vocabulary doubled, then tripled, so desperate was he to please Fr. Fleury. It was a task that demanded considerable effort, the priest’s attention was so clearly elsewhere.

Adult indifference, its power to motivate children, is old news in Catholic circles. My own mother practiced a version of this approach—by natural inclination, I suspect, more than by design. Fr. Fleury’s disregard was, to Art, oddly reassuring. He was unused to flatterers like Fr. Dowd, confused by male attention of any kind. With his stepfather, indifference was the best you could hope for. If you did anything to attract his notice, there would be hell to pay. But unlike Ted McGann, Fr. Fleury wasn’t volatile or angry, just preoccupied with other matters. Art lived to impress him. Years later he would recall the time he scored a 99 on a quarterly exam and was rewarded with a rare smile. He had made no errors, but Fr. Fleury did not award 100s. He subtracted one point, always, for original sin.

Art had never had a father. When Ma’s first marriage was annulled—literally made into nothing—Harry Breen was expunged from the record. Art was the awkward reminder of a union that had, officially, never been. Now, suddenly, he had more fathers than he knew what to do with: Fr. Fleury, Fr. Koval, Fr. Frontino, Fr. Dowd. They taught him more than Latin and history, algebra and music. By word and example they taught priestliness: ways of speaking and acting; of not speaking and not acting. Restraint and discipline, obedience and silence.

For a shy boy, these formulas were a help and a comfort. Art didn’t miss his old school, the rough-and-tumble Grantham Junior High. St. John’s was a haven from all that frightened him, the alarming interplay of male and female, that intricate and wild dance. Like many boys he feared the opposite sex. But even more intensely, he feared his own.

A certain kind of boy unnerved him, hale athletes, confident and aggressive. At seminary such specimens were blessedly few. From the first it was clear that a range existed: alpha males at the one end; at the other, the distinctly effete. Both extremes were, to Art, alarming. Like Latin nouns, the boys came in three genders, masculine, feminine, and neuter. He placed himself in the third category, undifferentiated. In the seminary at least, it seemed the safest place to be.

Matters of sex, of maleness and femaleness, were in this world peripheral. He felt protected by silence, grateful at all that was left unsaid. Once, at a Lenten retreat, Fr. Koval had delivered a steely sermon exhorting the boys to keep their vessels clean. To Art, at fifteen, the words remained mysteriously figurative, vaguely connected to all that had distressed him in his old life: at home, the nighttime noises from Ma and Ted’s bedroom; at school, the fragrant and fleshy presence of girls.

The life of a celibate priest. Fr. Koval had compared it to climbing Mount Everest: the outer limits of man’s capacity, a daring test that few were brave enough to attempt. The rhetoric was aimed at the boys’ nascent machismo; to Art, who had none, it rang false. A better comparison, he felt, was a journey on a spaceship. A priest was isolated and weightless. He existed outside gravity—the force that attracted bodies to other bodies, that tethered them to God’s earth.

Art grew up in this atmosphere, outside gravity. Troubling questions were answered for him, and he accepted these answers in gratitude and relief. So when he graduated from high school and entered the seminary proper, he was unprepared for the sudden change in the weather. That September a new rector was brought over from Rome, a strapping, ursine priest named James Duke.

The previous rector had been mild and scholarly, a soft-spoken man with a distracted air. But Il Duce was another sort entirely. He exuded, by priestly standards, an air of raw masculinity, and surrounded himself with others—Fr. Noel Bearer, Fr. Stephen Hurley—of the same type.

The new regime seemed, at first, comically harmless. Their demeanor struck Art as clownish, a self-conscious parody of manliness. Then came the warnings—repeated with ominous frequency—against particular friendships. This injunction was not new. Close friendships violated the spirit of community; they were contrary to the Rule. Under the old rector, particular friendships had seldom been mentioned; now, suddenly, they seemed a matter of great concern. No suggestion was made, ever, of illicit affections between the men; but everyone was aware of the subtext. Art found himself avoiding his best friend Larry Person, who shared his interest in music. They no longer rode the T into Boston to hear Sunday concerts downtown. Smoking in the courtyard between classes, Art took notice of who else was standing at the ashtray. Groups of three or four were acceptable. Twosomes were inherently suspect.

Among the men paranoia blossomed—fears inflamed at the end of the school year, when a few were told by their confessors that the faculty harbored concerns. Art’s old cellmate Ray Cousins was censured for his distinctive voice. The criticism was so vaguely worded that Ray didn’t understand, at first, why he was being scolded. True, he admitted to Art, he wasn’t much of a singer; but many a parish priest had learned to fake his way through the Mass. But Ray’s deficiency was not musical. His voice was high-pitched, with a discernible lisp. Suddenly Art no longer felt safe in the epicene middle. In the era of Il Duce, nobody was safe.

And yet somehow he came through unscathed; his own masculinity, however stunted and friable, was never questioned. At the time, and for years afterward, this fact astonished him. That spring he was chosen, at Fr. Fleury’s recommendation, to spend his four years of theology study at the Gregorian University in Rome, a rare distinction. To Clement Fleury he owed his escape.

I was a little girl when Art left for the Greg, too young to understand much of his business there. I do recall impressing my fourth-grade class with the postcards he sent me: the Colosseum and Forum and Trevi Fountain; multiple views of St. Peter’s, each bearing a florid stamp. Poste Vaticane.

One of these cards is still in my possession, a nighttime shot of the basilica Santa Maria Maggiore, an exquisite jewel box of a church. It is a glittering repository of Catholic treasure—priceless sculptures by Bernini and Jacometti, every flat surface bedecked with frescoes and mosaics. The ceiling, legend has it, is gilded in Inca gold. In Art’s opinion—inherited from Fr. Fleury—Santa Maria is more beautiful than St. Peter’s. Judging from my postcards, I would have to agree.

Meanwhile, beyond the seminary walls, the world was changing. Art had been baptized into one church, confirmed into another. A bold new pope, the astonishing Roncalli, had proclaimed an aggiornamento; a new day had dawned. The liturgy went from Latin to English. The altars were literally turned around backwards, and priests said Mass while facing the congregation. In choir lofts, organs were joined by acoustic guitars. It seemed inevitable that the changes would continue.

Art was twenty-five when he left Rome. He had traveled widely across Europe, seen every major cathedral in France and Spain. He returned to Boston with a powerful sense of mission, ready for ordination and all that lay beyond. Aggiornamento had inspired a whole generation. In Rome he’d met priests from Central and South America who spoke movingly of their people’s struggles, the church’s power to effect social change. Activism was the church’s future, and Art itched to be a part of it. For the diaconate year, as his classmates dispersed to local parishes, he was sent to a shelter for homeless men in the city’s South End. It was an unusual assignment, uniquely tailored to his tastes and aspirations. Once again, Fr. Fleury had worked his magic on Art’s behalf.

The South End has since gentrified, filled with posh restaurants and pricey boutiques; but in those days it still belonged to the poor. Each morning Art rode the T deep into Boston. At the shelter he ministered to the maimed and broken, the sick and delusional. There were men back from Vietnam, scarred by combat; lost inmates from state psychiatric hospitals decimated by budget cuts. There were addicts and runaways, boys barely out of childhood who came on buses to South Station and sold themselves on Washington Street. It was a veritable army of the needy, and yet the archdiocese paid little attention. When Art arrived there, only one priest was seen in the shelters and on the streets. Art knew him by reputation only: the Street Priest, young and longhaired, who walked the Combat Zone in vest and blue jeans, seeking out the lost. The Street Priest’s apartment on Beacon Street was a gathering place for the desperate, the lonely and addicted. On Sunday mornings he said Mass there, with twenty or thirty runaways sitting Indian-style on the floor.

To Art it seemed the stuff of urban legend. He himself had handed out blankets and the Eucharist, but certainly he was no Street Priest. In his first week he was mugged at knifepoint. At the shelter he was treated as a curiosity, when he was noticed at all. If the Street Priest was the clergy’s future, Arthur Breen felt better qualified for the past.

In other ways, too, the future frightened him. The celibate priesthood—would it go the way of indulgences and Latin?—was a point of fierce controversy. He’d been a boy at St. John’s when he first heard this debate. At the time it caused him considerable distress. The priesthood had seemed to him ancient and unchanging. That it might, in a few years, transubstantiate he found deeply unsettling. He’d been prepared and willing, at the rash age of fourteen, to give himself over to it entirely, in exchange for certain protections. He’d marked it definitively as his safe passage through the world, the only life, perhaps, to which he was suited. It seemed impossible that his church would betray him in this way, change so profoundly the rules of the game.

This story is adapted from the forthcoming book Faith: A Novel, by Jennifer Haigh. Copyright 2011 by Jennifer Haigh. To be published on May 10, 2011, by Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Read more fiction from Commonweal here.