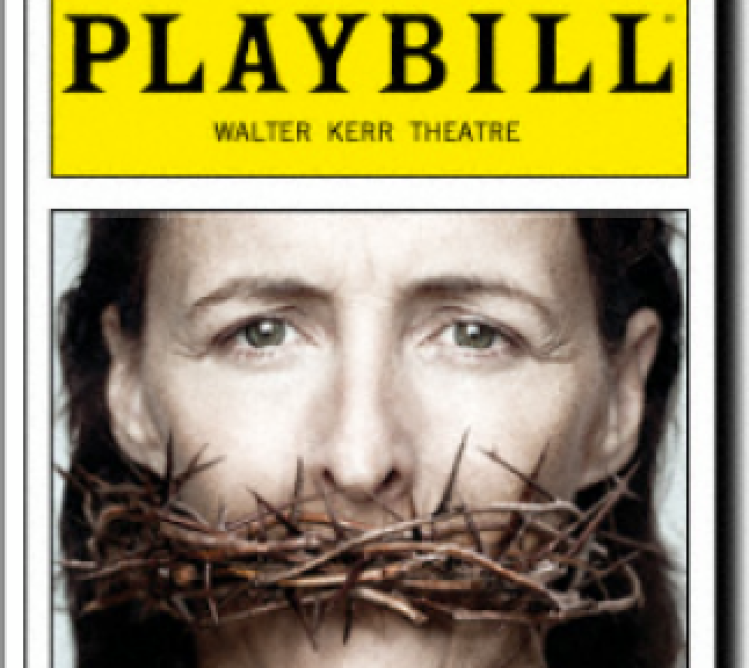

Broadway’s most recent foray into Catholicism has come to an abrupt halt: The Broadway testimony of the mother of Jesus—as written by the award-winning Irish writer and onetime altar boy Colm Tóibín and spit out with furious anger by the formidable Fiona Shaw—will shutter on Sunday, May 5.

The closing of the The Testament of Mary, after only forty-three preview and regular performances, was announced hours after Shaw failed to garner a Best Actress Tony nomination on April 30 (and despite three Tony nominations, including Best Play). The end of the run meant that New York audiences would be deprived of what proved to be an uneven but powerful night of provocative theater. The play, adapted from Tóibín’s short 2012 novel of the same name, presented an overwhelmingly grief-stricken mother of Jesus who, convinced that his crucifixion was an unnecessary horror, is entirely uncomforted by what she believes are fictions of deity and redemption.

The play, directed by longtime Shaw collaborator Deborah Warner, drew objections early: Conservative Catholic group The American Society for the Defense of Tradition, Family and Property (“an organization of lay Catholic Americans concerned about the moral crisis shaking the remnants of Christian civilization,” according to its website) staged a protest at the show’s first preview performance, which just happened to fall on Tuesday of Holy Week. The show’s producers were probably not taken by surprise; in fact, they may have counted on the TFP’s placards to gin up interest and ticket sales.

Tóibín, for his part, had certainly hoped the play would provoke conversation, something he made clear in an interview with me before the show opened. He comes out of an Irish tradition, he said then, “where the theater really matters, where the theater affects public life in a very serious way, where images in the theater are not to be taken lightly.” (He cites by way of example the impact made in the early 1980s by Frank McGinnis’s play Observe the Sons of Ulster Marching Towards the Somme.) So Tóibín’s play, with its exploration of a Mary entirely unfamiliar from the ubiquitous placid, passive one, came from what the writer called “a serious place.”

Controversial? Likely. Challenging? Certainly.

“It’s an unimaginable idea that somebody would go through their lives without having their beliefs challenged,” Tóibín said. “Yes, this might upset people, but the idea of living your life without having your basic beliefs upset, for me would be a life not lived. However,” he continued, “the idea of having them mocked would disturb me.”

Tóibín, fifty-seven, is a self-described lapsed Irish Catholic who has not, however, rejected his cultural upbringing. “I find it impossible to believe,” he said. “But the iconography, the prayers, the entire basis of worship, I spent so long with it that it’s in my dreams. So you can’t merely say it doesn’t matter. But intellectually, if I were pressed, I can’t see it; I just can’t see it.”

The Testament of Mary was indeed intellectual and provocative, but not irreverent or blasphemous, and the theatergoers who attended were engaged by a harrowing, human, recognizable, maternal Mary, even if the play’s direction and the star’s turn tended toward too much sound and fury. (More than a few critics lamented the fact that Shaw wasn’t allowed to deliver Tóibín’s lines more simply, with less running around and knocking things over.)

In balance, the show’s rapid close is a defeat at the hands of entertainment reality (as Variety put it the day after the closing was announced, the show “never caught on with auds”), rather than a victory of a fundamentalist religious or moral sort; the TFP didn’t respond to a request for a comment after the closing, though its Facebook page acknowledged the fact with a thanks for the prayers that presumably helped bring down the shutters. It is also a disappointment for those interested in thinking seriously about faith. But the fact that the show was mounted on Broadway at all gives it an attractive pedigree, and Tóibín says there are already productions in the works in Spain, Brazil, Denmark, and other countries.

Further, the closing may afford an occasion to revisit the controversial book that led to the play. The novel, itself an adaptation of a stage production (then called Testament) that took place at the 2011 Dublin Theater Festival, drew a good deal of attention, much of it elegiac, some vitriolic, for its re-imagination of Mary. As in the play, this mother of Jesus is bitter in her recriminations and entirely lacking in faith of any sort, both in her Judaism (“All of that is gone,” she says) and the nascent movement named for her son. She does seem to be drawn to the pagan goddess Artemis. Mary’s interpretation of the events surrounding the Passion is that Jesus (she never says his name), who “could have done anything,” gathered around him “a group of misfits, who were only children like himself, or men without fathers, or men who could not look a woman in the eye.” (Tóibín transferred that line essentially untouched to the play, and in Shaw’s delivery of it became a scathing denunciation of basement-dwelling zealots and oddballs.) Mary believes it was the adoration of her son’s followers that pulled him toward trouble with the authorities, a horrific death, and ultimately the creation of a cultish fiction in which that death is absurdly seen as redeeming the world. This Mary, unlike the cipher of a character who inhabits the Gospels as the willing and agreeable handmaiden of the Lord, is essentially held captive by her son’s weirdo disciples, who fervently desire that her story support the one they’re developing. She will have none of it.

Tóibín’s novel is challenging but genuinely worthwhile, perhaps the more so because it is discomfiting; the book, which Warner, Shaw, and Tóibín worked to pare down significantly for Broadway, is in ways a more intense experience than watching the play. The book’s Mary is unrelenting in her crabbed anger, whereas Shaw’s performance found frequent glimmers of humor. Mary’s anti-spirituality comes initially as a shock, but it succeeds in getting the reader to think about her in an unusual light, and Tóibín is clear that he is working in the realm of fiction. Indeed, canonically critical timelines are reworked—most notably, the raising of Lazarus precedes the wedding feast at Cana—such that it is evident that Tóibín is exploring a character, a tragically grieving human mother, and not offering a historical portrait. He had narrative needs as a storyteller, he said, that took precedence over adherence to Gospel truth.

The book stirred outrage when it came out in November of last year, so it was no surprise that the play met with protests. But if the adage is true that there’s no such thing as bad publicity, then the producers may well have been disappointed there weren’t more outraged protests. Even the Catholic League’s William Donohue yawned: Tóibín “is “entitled to his views,” he declared, “though it must be said that his attempt to persuade Christians of the fallacies of their religion falls flat.” Critical assessments ranged from middling to ecstatic, with reservations particularly for director Warner’s constant bits of stage business, and accolades going to Shaw’s performance. What few reviews suggested, however, was that this was must-see theater, or even particularly entertaining theater.

This may have suited Tóibín’s earnest intentions. “I wouldn’t think of the theater as a place to be entertained,“ he said. “I know that some people do: Well, I don’t.” Opening on Broadway, for him, wasn’t about entertainment, but about reaching a large, audience that would in ways replicate the Dublin audience that defined the kind of serious theater tradition he comes from: a mixed audience, an audience that doesn’t necessarily think of itself as literary. “You’re actually having an impact on people“ with that kind of audience, he said.

And that, after all, is what The Testament of Mary was, at least on some levels, trying to do. (It was also trying to make a buck, and its failure there spelled its demise.) Like its progenitor novel, it is fiction, and should perhaps even be called speculative fiction—to borrow the term typically reserved for what is frequently called sci-fi—providing a setting in which to explore truths perhaps at odds with plaster pieties. There’s great value in that for the curious faithful, and the faithfully curious.