“I really don’t know how to explain it,” Archbishop Anthony Bloom said, “but it seems to me that the word ‘belief’ is misleading. It gives the impression of something optional, which is within our powers to choose or not. What I feel very strongly about it is that I believe because I know that God exists, and I’m puzzled how you manage not to know.” This was forty-some years ago, and the Orthodox priest was a guest on a BBC television program, in respectful conversation with a similarly respectful atheist.

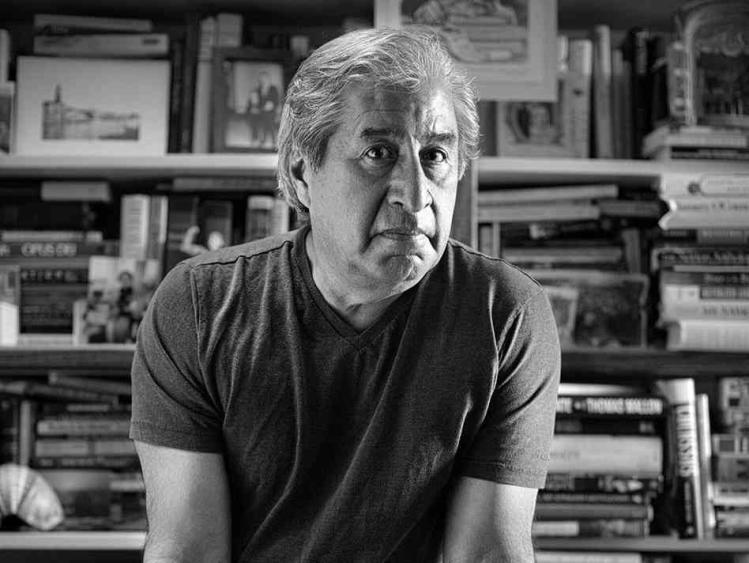

Richard Rodriguez doesn’t really know how to explain it either. “Our lives are so similar, my friends’ and mine,” he writes. “The difference between us briefly flares—like the lamp in my bedroom—only when I publish a religious opinion.” He refers to the flare that had awakened him one night, afflicting him with the certainty that his mother had died.

Rodriguez’s Darling: A Spiritual Autobiography is a collection of ten numinous essays, published in various publications over the years since that bright autumn morning when a band of airliner-hijacking jihadis afflicted our world with a related certainty. It is eclectic in a way with which all of us Rodriguez fans are familiar: there is superb travel writing here, some wry fun poked at the green movement, a profound reflection on how heterosexual women have midwifed the emancipation of gay men, and even a paradoxically reverent deconstruction of César Chávez. And whether or not that subtitle is strictly accurate, there is enough honest puzzlement, enough articulate bewilderment in every sentence to provide a compelling glimpse, if not a well-shaped narrative, of a man’s spiritual life.

The man is a Catholic, Mexican-American, homosexual, baby-boomer Californian public intellectual, beholding, among other astonishments, “the dawn of a worldwide religious war that Americans prefer to name a war against terror,” and knowing a soul-kinship with young men who sang prayers to God while they slaughtered innocents in a cornflower-blue Manhattan sky: “I do not believe what the destroyers believed—that God is honored by a human oath to take lives. I do not believe that God can be dishonored. The action of the terrorists was a human action, conceived in error—a benighted act. And yet I worship the same God as they, so I stand in some relation to those men.”

Rodriguez stands in such relation—not only to holy warriors, but to culture warriors, to Saints Francis of Assisi and Thérèse of Lisieux, to the pedophile priests and their fatuous bishops, to the Sisters of Mercy and the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence—as a son of one of the three desert religions fathered by Abraham. His doubt-seasoned Catholic belief reveals the time he inhabits as out of joint, freeing him from what Chesterton called “the degrading slavery of being a child of his age.” He’s as free as a suicide bomber, this master of the literary essay.

“To speak of the desert God is to risk blasphemy,” he writes, “because the God of the Jews and the Christians and the Muslims is unbounded by time or space, is everywhere present—exists as much in a high mountain village in sixteenth-century Mexico as in tomorrow’s Jakarta, where Islam thrives as a tropical religion.” The remark is from “Jerusalem and the Desert,” a Harper’s magazine piece on a visit to the Holy Land. This essay also includes a passage, too long to quote here, which is (in the humble opinion of at least one reader) as fine an account of God’s encounter with Abraham as any to be found outside Genesis 18:1–2. The Holy Land, where Christian monks of various denominations squabble over custody of a piece of real estate whose sole significance is that Jesus is not there, where Muslims insist that there is no god but God and that it is better to pray than to sleep, is also where, Rodriguez observes, “the desert encourages a sense of rebuff and contest with the natural world. Jesus cursed the recalcitrant fig tree right down to firewood.”

That desert, and so the God revealed there, are never very far from these pages, as when Rodriguez travels to Las Vegas during Holy Week to visit the deathbed of a friend and notices, along with an intimate reiteration of Christ’s passion, how “a vacation city must be defiant of death, Las Vegas doubly so, for it is a city built on a desolate landscape. My predicament is that I am here for death, and the city of distraction is in my way.”

All the essays in Darling concern that predicament, the distraction the Fathers of the Desert knew and named as demonic, which occludes the experience of true presence and therefore prevents one from keeping company with God. No wonder differences flare up from time to time with nonbelieving friends. How do they manage not to care?

In the last essay, “The Three Ecologies of the Holy Desert,” Rodriguez embeds a splendid memory when a moment of grace evaporates distraction. It involves his friend Wayne, a San Francisco beggar, whom he has spotted on the sidewalk just as “several things happen simultaneously”: an old man nearby, another street denizen, begins to sing “When You’re Smiling,” a young man appears suddenly and seats himself next to Wayne proffering a pink box of doughnuts and a cup of coffee, and then

Wayne smiles with pleasure, catches my eye as he reaches for a doughnut, and is momentarily connected to the old man singing “When You’re Smiling,” for he and the other—the doughnut bringer—in mock-mockery, begin to sway to the cadence of the song like two bluebirds on a bough in a silly old cartoon. The sun, too, now seems a simple enough phenomenon—cadmium yellow pouring onto the pavement. A passerby drops a bill into Wayne’s cup and Wayne nods and smiles (and looks over to me). I smile. The design—tongue and groove—of a single moment....

But here’s the thing: Wayne’s smile.

I have thought about this for twenty years or more. Wayne’s smile said: Do you get it? Wayne’s smile said: Remember this moment, it contains everything.

Those moments when the desert God smiles: to notice them is, of course, a blessing, but to remember, retrieve, and convey them is literary work. We should be grateful to Rodriguez for working so hard.