“I have always been inclined to take the papal encyclicals seriously.”

In The Brothers Karamazov there is a character named Miusov who quotes a French police official: “We are not particularly afraid of all these socialists, anarchists, infidels and revolutionaries; we keep watch on them and know all their doings. But there are a few peculiar men among them who believe in God and are Christians, but at the same time are socialists.Those are the people we are most afraid of. They are dreadful people! The socialist who is a Christian is more to be dreaded than the socialist who is an atheist.”

Recently I went into Boston and joined the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee. The DSOC was organized by members of the left wing of Norman Thomas’s old Socialist Party who split off a few years ago because the dominant right wing could not shake its fear of Communism long enough to give up on Vietnam and other visions of America as savior and policeman of the world.

Short of some unlikely fluke that might put George Wallace on the Democratic ticket, the DSOC is committed to working within the Democratic Party. Its chairman Michael Harrington is the author of the book The Other America that helped start the war on poverty. He came out of the Catholic Worker in the fifties. No longer a Catholic, he is somewhat more bemused by Marx than types like Thomas, who once wrote, “For me the outstanding fact about it (Marxism), despite its proven power, is its inadequacy for our time under any interpretation.” But Harrington’s devotion to democratic process is without question, as is his rejection of Stalinism and other Marxist aberrations.

Among DSOC members are such distinguished people as John Kenneth Galbraith, Irving Howe and Victor Reuther, and, from the Catholic community, Peter Steinfels and David O’Brien.

The DSOC program includes proposals to nationalize at least part of the defense industry and banking, set up the federal gas and oil corporation proposed by Senator Adlai Stevenson, establish a national planning mechanism to develop a long-range policy for energy and transportation, and the following interesting plank: “Employee and public representatives should be placed on the boards of directors of all major industrial and financial corporations with instructions to violate the canons of managerial secrecy and to inform the public of bias of pricing, technology, plant location and other policies of these corporations.”

Why did I join? Since conversion to Catholicism in 1933 I have always been rather conservative in theology and inclined to take seriously the opinions of the Popes as expressed in their encyclicals. From these I absorbed the anti-socialist bias that most Catholics in America share. Combined with this was a deep suspicion of public ownership that was rooted in part in Eric Gillian devotion to the idea, “Men work best when they own and control their own tools and materials,” an aphorism I picked up when I found it lying around the Catholic Worker in the thirties.

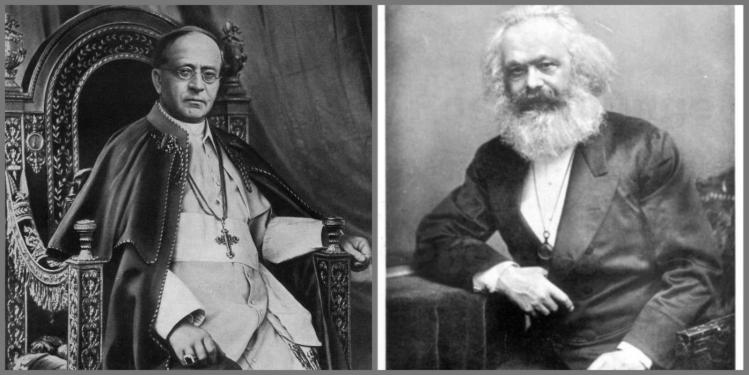

There are of course good reasons why we might not want to be socialists, whether we be Christian, Catholic, or otherwise. Socialism finds it difficult to free itself from the specter of Karl Marx, who does not make a comforting bedfellow. As I think Barbara Ward pointed out in his behalf, Marx’s scathing critique of capitalism qualifies him for inclusion among the last of the Jewish prophets. On the other hand, his atheism, his depressing materialism and determinism, his naive faith in the panacea of public ownership, his failure to grasp the relationship between freedom and private property, his idea of the dictatorship of the proletariat and all the nasty little justifications that have sprung from it, as from Pandora’s box, that the end justifies the means, his childish fancy that the state will wither away once private property and exploitation have been abolished-all these combine to make him, in my opinion, one of the world’s more overrated thinkers.

Harrington, one of the most persuasive defenders of Marx, in his excellent book Socialism makes the point that Marx was really a democrat at heart and that when he wrote “dictatorship of the proletariat” he really meant democracy because he regarded the bourgeois democracies of his day as so many dictatorships. But Harrington does not explain how it follows from proving that a so-called democracy is really a dictatorship that therefore a dictatorship is really a true democracy, so to this extent he is less than persuasive.

It makes some sense to say that the answer is not socialism, however democratic, but simply democracy. If we define socialism in terms of state ownership and control of the means of production, as many people do, then socialism is incompatible with democracy, since democracy requires that power should be distributed as widely as possible, and productive property is power par excellence.

It makes some sense to say that what we need is simply to extend democratic process from the political arena, where it has been continually corrupted and weakened by industrial and economic oligarchy, to the world of the factory, office, bank and industry, so that the workers begin to own and control directly the means of production upon which their working and consuming lives depend. A key word here is “directly.” It is not realistic to think that you can control state-owned factories through elected congressmen and/or the president. Watergate should have taught us how far an elected official can wander from the mind and will of the people.

Harrington is aware of the dangers of public ownership, or state capitalism, as it might better be called, because he quotes the old French socialist, Jean Jaures, in a key passage:

“Delivering men to the state, conferring upon the government the effective direction of the nation’s work, giving it the right to direct all the functions of labor, would be to give a few men a power compared to which that of the Asiatic despots is nothing, since their power stops at the surface of society and does not regulate economic life.”

Jaures went on to propose, in 1894, that the French mines be nationalized but actually operated by “a central council with one-third of the members elected by the workers (including the engineers), one-third from workers’ and peasants’ unions in other areas of the economy, and one-third named by the government.”

I like that kind of arrangement myself, where nationalization is found to be necessary. Yugoslavia has developed a system under which the state owns productive property and the workers, theoretically, operate it. But often only theoretically. For what the state hath given the state can taketh away. So where nationalization is not necessary it makes sense to leave the ownership and control mainly and directly in the hands of those who work in the enterprise. Nationalization becomes the exception, not the rule, and what you have is democratically owned and operated private property; or, industrial and economic democracy. We have also Pius XI’s principle of subsidiarity, expressed neatly by Richard Goodwin in the New Yorker: “The general rule should be to transfer power to the smallest unit consistent with the scale of the problem.”

There are also a number of good reasons why we should become socialists, despite the considerations outlined above. For one thing, socialism today cannot fairly be defined either in terms of Marxist theory in general or state ownership in particular. The DSOC, for example, uses the term “social ownership,” as did Norman Thomas before it. The word “social” is broad enough to include enterprises owned and operated by workers or consumers, as in the producer and consumer cooperatives so popular in England.

Most of the socialist parties of Western Europe have become disillusioned about the automatic benefits of state ownership and no longer identify socialism with that solution, although public operation of utilities and key industries is much more common in Europe than in America.

After all, did not Pius XI say that “certain forms of property must be reserved to the State, since they carry with them an opportunity of domination too great to be left to private individuals without injury to the com munity at large”? And could it not also be contended that these forms include a far larger area than is presently recognized in America, such as defense industry, energy, railroads, investment banking, health services, and even low-income housing construction?

Most European socialists are now more excited about getting workers direct control over productive enterprise, as in the co-determination movements of Western Germany, Scandinavia, and the Low Countries, now spreading to France and Great Britain. Many European Catholics are supporting them in this, notably among the Christian and former Christian (French) trade unions. And they are only following the lead of Pope John in Mater et Magistra (1961) when he wrote that it is not simply a good idea, as Pius XI had suggested, but “a demand of justice” that at least “large and medium-size productive enterprises (which) finance replacement and expansion from their own revenues . . . should grant to workers some share in the enterprise.” From the context it is evident that John meant share of ownership, or social ownership. And he adds this reason for going further than Pius: “For today, more than in the times of our predecessor, ‘every effort should be made that at least in the future only an equitable share of the fruits of production accumulate in the hands of the wealthy, and a sufficient and ample portion go to the workingman.’” The quote within the quote is from Pius.

(Sidenote: it is interesting that a nationwide poll taken by Hart Research Associates, reputable pollsters, and funded by the People’s Bicentennial Commission, indicates that 66 percent of Americans feel that it would do “more good than harm” to “develop a program in which employees own a majority of the company’s stock,” while only 25 percent feel that it would do “more harm than good.”)

Incidentally, it is now fashionable for Catholic liberals to ignore encyclicals as exercises in irrelevance, but time was when they smote their enemies over the head with them with all the enthusiasm of Samson smiting the Philistines. Even Tom Hayden and the SOS once seized upon them to make a point. In the expectation that the pendulum of concern, having swung from one extreme to the other, will soon swing back to some kind of happy medium, these observations are offered as part of a relevant historical record as to what Catholic authority has taught and teaches on the subject of socialism and capitalism.

A case could be made for the proposition that the socialist parties of Western Europe and Great Britain come closer to representing the view of the encyclicals, in practice if not in theory, than do the Christian Democratic parties that claim direct kinship with those writings, but whose zeal for social justice is too often neutralized by the rich folks in their midst.

Many socialists also have no illusions about the infallibility of Pope Karl I. The Frankfurt Manifesto of the Socialist International stated in 1951 that one may be led to the socialist position not only by the Marxist social analysis but also by humanitarian ideals or belief in Christian revelation. This is a point made by Oswald von Nell-Breuning, the German Jesuit who is generally credited with having written much of Pius Xi’s Quadragesimo Anno as well as the first draft of John’s Mater et Magistra.

Writing in Sacramentum Mundi, an encyclopedia of Catholic theology published by Herder & Herder in 1968, Father Nell-Breuning acknowledges that Pius XI condemned socialism when understood as a materialist philosophy which sacrifices freedom and higher human values in the interests of efficient production and distribution of goods. He immediately points out, however, that “it is certain that forms of socialism: existed in 1931 which did not exhibit the features described in the encyclical (Quadragesimo Anno) and accordingly were not affected by the papal condemnation-the British Labor Party for one (which the Archbishop of Westminster hastened to reassure on this point) and probably Scandinavian socialism as well.” Nell-Breuning concludes that “the libertarian, democratic socialism of the present day has clearly ceased to be” the kind of socialism condemned by Pius XI. He further notes that John XXIII confirmed this conclusion by conspicuously failing to reaffirm the interdict in his own encyclicals. Nor has Paul VI reaffirmed it.

Nell-Bruening adds the observation: “Now that movements have arisen in the newly independent Afro. Asian countries which regard themselves as ‘socialist’ but have almost nothing in common with what has been known pejoratively as socialism, even in the broadest sense, it is less possible than ever to pass any global judgment on socialism....Were the Church to condemn ‘socialism’ in general, the result in these countries would be the most baneful confusion and dismay...

It is significant that Monsignor George G. Higgins of the U.S. Catholic Conference, in a polite rebuke to the Most Rev. Robert Dwyer, retired archbishop of Portland, Oregon, recently quoted key passages from Nell Breuning’s article in refuting the Archbishop’s claim that the Catholic Church has always condemned so alism.

Actually, Monsignor Higgins accepts the common dictionary definition of socialism as “based on collective or governmental ownership.” As such he himself rejects it. But Nell-Breuning appears to appreciate the fact that socialism today can be more accurately defined as a democratic system of political economy which rejects the capitalist notion of production for profit (or power) and affirms the notion that production should be controlled by workers and government in the interests of the many rather than the few. It seems to me that this is a concept which Monsignor Higgins should approve as representing the main thrust of his own thought.

The word “socialist” has the advantage of instant reception in identifying the bearer as both democratic and anti-capitalist, an advantage which the word “democratic” alone does not have. Up to now I have been assuming that the reader would want to be identified as anti-capitalist. Perhaps that assumption should be supported.

In the minds of many people capitalism is confused with private ownership of the means of production. They rightly believe that private ownership of most productive property is necessary to the preservation of liberty from the tyranny of the state, and that where public ownership is necessary it should be regarded as a last resort and watched like a hawk. But the truth is that capitalism cannot accurately be identified with private ownership. Capitalism is a particular kind of private ownership, a system under which the representatives of capital are left in the undisputed control of the decisions as to what to produce, how to produce it, and what to charge for it. The system tends to be marked by decisions which are in the interest of those representatives and not in the interest of workers, consumers, the general public or the world at large.

Galbraith makes the point that these decisions are not necessarily inspired by a desire for maximum profits. They may be inspired by the desire for power, prestige, or simple security on the part of the de facto managers or, in his term, the corporate technostructure. It’s a valid point, but it does not usually make the social effects of the decisions, any more attractive.

Pius XI described and condemned capitalism in Quadragesimo Anno in the following words: “In our days not alone is wealth accumulated, but immense power and despotic economic domination is concentrated in the hands of a few . . . This accumulation of power (is) the characteristic note of the modern economic order . . . Free competition is dead; economic dictatorship has taken its place… The whole economic life has become hard, cruel and relentless in a ghastly measure.”

This blistering indictment could have been helpful in clarifying the minds and consciences of Catholics. The only trouble was that in the same encyclical the Pope also said that in so far as capitalism is defined as “that economic regime in which (are) provided by different people the capital and labor jointly needed for production . . . the system itself is not to be condemned.″ He then went on to condemn it when defined in his own terms, as the above quotes indicate.

The confusion of Catholics as to whether their church did or did not condemn capitalism was further magnified in this country by our partial recovery from its dramatic collapse in the Great Depression, which had formed part of the backdrop for Quadragesimo Anno. So dramatic and traumatic was the collapse that in 1938 Congress, reacting slowly, established the O’Mahoney Committee to find some answers to what ailed us. But then came the war(s). The young men died, but most of us did okay. Capitalism fed on death and was re stored to a measure of life. The O’Mahoney Committee folded its report and silently stole away. New Deal reforms slicked the system over, so that people began to think we had something new, something they called “welfare capitalism.” One effort at structural change, the National Recovery Act, was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court.

In the great organizing drives of the thirties and forties labor unions established a kind of democratic beachhead on the mainland of corporate decision-making, at least as to wages, hours and certain other conditions of work. Most workers seemed content with this as long as they went on working and rising wages kept at least a nodding acquaintance with rising prices. Labor leaders, who once came on as champions of the poor, began to sound like champions of the establishment.

Lately, however, we have been suffering from too much peace. Capitalism has been languishing for lack of blood. Workers haven’t been working, consumers haven’t been buying, and, marvelous to tell, in the face of all the ancient folklore, prices have continued to rise so that the wages of those still working haven’t been able to keep up. Inflation is running about 12 percent per annum and unemployment close to 9 percent. So once again, as we prepare to celebrate another bicentennial, that of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, some of us are questioning his beautiful childlike faith that if only the rich are left free to pursue riches, then all boats will be lifted on the rising tide of their good fortunes.

The tide has now gone out and many of the boats are beached, with a slight assist from the Arabs. And America is hated all over the world for permitting its multi national corporations, when it is not actually assisting them, to crucify the poor in Asia, Africa and Latin America, as has been exhaustively and depressingly documented by Barnet and Muller in Global Reach.

Some people have maintained that Christ had no economic program. I disagree. “Give us this day our daily bread” is an economic program that convicts capitalism out of hand. A more detailed indictment is contained in Jesus’ vision of the last judgment in which, with an old-fashioned lack of tolerance, He consigns to “that everlasting fire prepared for the devil and his angels” all those who refuse to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, shelter the shelterless, comfort the sick and the prisoners, etc. (Question: doesn’t it seem extraordinary that for many years this passage, surely one of the most basic in all scripture, was excluded from those to be read at Sunday Mass?)

“By their fruits shall you know them” is another Gospel passage that Christians should take seriously. By the fruits of capitalism-notably its concentration of power and wealth in the hands of the few while many go without, its dependence on war and/or ridiculous “defense” expenditures, its exploitation of the poorer peoples of the world-it stands condemned as unChristian and unjust.

I assume that Christians want an economic system that can be reconciled with their faith. But just as the word “democratic” is not enough, neither is the word “Christian.” It is at once too general and too specific. America is in bad shape. And we have a nice man in the White House who is more outrageously besotted with capitalistic nonsense than anyone since Herbert Hoover. There is a need for those who reject this nonsense to come together under some banner that pro claims clearly and immediately that we do reject it, that we want to see the system fundamentally changed, that we want to see it freed from the control of the rich and the greedy and brought under the control of workers, consumers and government. There is a need for such people to form coalitions and alliances with others, in the labor movement, among intellectuals and minority groups, ethnics and non-ethnics, religious and irreligious people, so that they can have maximum impact on the Democratic party’s selection of its candidate and its platform in 1976.

Even democratic socialism, whether in America or abroad, will probably retain some traces of Marxism, at least in theory if not in practice. This should not prevent us from extending the hand of cooperation and support. Somebody once said that “every heresy is the revenge of a forgotten truth.” Pope John, the great apostle of cooperation, confirmed this in Pacem in Terris (1963) in a passage which obviously applies to the relations between Christians and Marxists:

“Meetings and agreements in the various sectors of daily life between believers and those who do not believe . . . can be occasions for discovering truth and paying homage to it. It must be borne in mind, further more, that false philosophical teachings regarding the nature, origin and destiny of the universe and of man cannot be identified with historical movements that have economic, social, cultural or political ends, not even when these movements have originated from those teachings and have drawn and still draw inspiration from them . . . Besides, who can deny that these movements, in so far as they conform to the dictates of right reason and are interpreters of the lawful aspirations of the human person, contain elements that are positive and deserving of approval?”

I don’t think I have thrown much light on why Dostoyevsky’s Frenchman thought that Christian socialists were so “dreadful.” Whether or not I have thrown any on the opposite proposition, whether or not we decide to call ourselves socialist and join the DSOC, it seems appropriate to point out that the following changes in our American system of doing business are entirely consistent with Catholic teaching:

1. A much stronger role by government in the owner ship and control of elements in our economy that involve a significant ’public interest.

2. A provision that corporations doing business with the federal government be required, as a condition of that business, to give a significant percentage of their voting stock to their employees, redeemable on termination.

3. A provision that the boards of directors of such corporations must include at least two members elected by the employees and at least two consumer representatives appointed by public authority.

4. Enactment of the old CIO plan for industry councils representing labor, management, consumers and government in a comprehensive system of economic democracy.

Actually, it’s a rather modest program, tailored to the country’s natural conservatism. But it could be the herald of a new birth of freedom. And that would be nice to see as we celebrate the bicentennial of another event even more memorable than the publication of The Wealth of Nations.