When I first read Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, which was published in 1968, the futuristic setting of the novel (1992) seemed far distant. In later editions, issued well after Dick’s death, the date of the action—and of World War Terminus, which precedes it, offstage—was pushed forward, into the 2020s, in an attempt (misguided, I think) to trick the reader. Pretty soon, it will need to be pushed forward again. The Future is elusive.

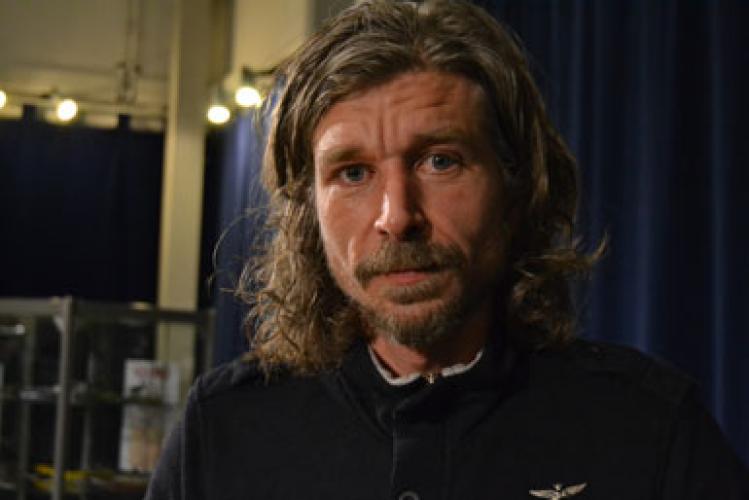

No one, no literary seer—as far as I know—predicted that the most striking literary phenomenon of the early twenty-first century would be a six-volume series by a Norwegian writer titled (who would have had the nerve to foresee this?) Min kamp, My Struggle, and cast as a novel, yet a novel about the life of the author himself, Karl Ove Knausgaard, his parents and his wives and his children, his friends and his enemies and his acquaintances, his relatives and his elementary school teachers, and countless others. After the spectacular success of the first volume in Norway—soon to be repeated elsewhere, not on the same scale but exceeding what anyone could have foreseen, as translations began to appear—howls of outrage were heard, and members of Knausgaard’s father’s side of the family disowned him. The second volume—A Man in Love, as the English translation is called, centering on Knausgaard’s second marriage, and the experience of fatherhood—hit his first wife like a gut punch and prompted rejoinders from her, which took their place in the ever-building legend, still growing today.

That first volume, published in Norwegian in 2009, appeared in the United States in 2012, published by a very fine small press, Archipelago Books, and translated by Don Bartlett, who is scheduled to bring the entire six-volume series, some 3,600 pages, over into English. The translation of Book Two followed in 2013, and Book Three, Boyhood, late this spring.

On the day I received my review copy of the third volume (having earlier devoured the first two), I discovered a small, purplish lesion on my penis. This would have disturbed me greatly had I not had a similar experience last November, when I was quite upset and thus nonplussed when the doctor said he wasn’t sure what it was or why it had appeared but no big deal, and here was a prescription for some ointment. Two days later...

That’s probably enough. You get the point; you discern my shameful ambition, my dream that Lorin Stein, the superb editor of the Paris Review, would say that “Mr. Wilson’s invention of a reviewer who is a real person and is in charge of the review has solved a big problem of the contemporary book review,” bringing new life to a genre that many have dismissed as moribund. “Wilson is utterly honest, unafraid to voice universal anxieties,” James Wood would add. And, best of all, Zadie Smith: “John Wilson. ‘My Review of My Struggle.’ I just read this five times and I need his next review like crack.”

Of course, to revolutionize the book review, I would need to do more than reveal my own yearnings and humiliations—I would need to bring my “candor and fearlessness” to bear on my friends and family too, “not for shock value or self-indulgence, but to show that plainspoken honesty gets to the heart of the human condition,” as the Kirkus review of “My Review of My Struggle” would put it.

All right, I promise: no more of these disgusting platitudes. Plainspoken honesty! Without artifice! Nothing in literature is more saturated with artifice than the pose of a man who rolls up his sleeves and says, “I’m just going to write what happened.” Compared to that, the conventions of the sonnet or the verbal duels of Restoration drama are without contrivance. Knausgaard himself has probably vomited more than once reading such absurd praise, or drunk himself into a stupor and then vomited: first, because he knows that what’s being said about him and his writing isn’t true; second, because he knows that there are passages in My Struggle (and, especially, bits in idiotic interviews he’s given) that—taken in isolation—seem to encourage such banalities. But ultimately Knausgaard himself can’t be blamed for such flagrant misreadings, for, far from constituting a triumph of plainspoken honesty and freedom from literary artifice, My Struggle is as twisty (hence as true to our twisty nature) and as stylized as Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground. What makes it a work of genius, for all its flaws (and they are many), is that the twisty self-consciousness that animates My Struggle is capacious and generous as well, acutely registering all manner of quotidian joys and sorrows and fluctuations of the spirit in a way that the modern masters of the perverse (you can supply your own list) would never allow themselves (they have a horror of “sentimentality”). Brooding, funny, tender, sometimes mired in navel-gazing, at other moments delivering revelations, shifting effortlessly from kitchen-sink realism to reflections on Holderlin, childhood memories of comic books, pop music of the 1980s, Hazlitt-like rants on the conformist culture of Sweden, the horror of endless diaper-changes, and much more, My Struggle is not going to change the course of literature, but it will more than adequately repay your time and attention.

In the first three volumes of the series, Knausgaard plays with chronology, both on the large scale (the sequence of the three books) and the small scale (within individual volumes). So, for example, Boyhood is the third volume, not the first, and within any of the first three books, he’ll jump to a time later (or earlier) than the time of the principal action of that volume.

The subject at the heart of Book One is the death of Knausgaard’s “Dad,” a teacher for most of his working life, a man of meticulous habits, who ends up drinking himself to a premature death in utter squalor. Not until Book Three, when the author turns to his childhood, do we fully grasp what a malign presence “Dad” has been for Karl Ove, though there are clear indications of this from the start. Beginning with reflections on how we deal with death and the bodies of the dead, shifting around in time (in a very early scene, Karl Ove is eight years old), the narrative of Book One builds to an extraordinary set-piece that takes up roughly the last 150 pages of this volume of 430 pages.

Karl Ove and his brother, Yngve, have driven to Kristiansand, the town where their father had been living with his mother. They meet with the undertaker to make arrangements, then go to the house. Bottles are everywhere; rooms are piled with junk; a terrible stench is coming from somewhere, though not from the room where their father died, near the giant TV. Their grandma is suffering from dementia, and she stinks of urine. The brothers set out to clean the place up and restore some order.

This extended narrative, one of the most sustained in the first three books, never flags. Absurdity, pathos, and gallows humor mingle. Having visited their father’s body once, Karl Ove—after Yngve has left, to return in several days for the funeral—decides to visit him again at the chapel, and the following passage concludes the book:

This time I was prepared for what awaited me, and his body...aroused none of the feelings that had distressed me before. Now I saw his lifeless state. And that there was no longer any difference between what once had been my father and the table he was lying on, or the floor on which the table stood, or the wall socket beneath the window, or the cable running to the lamp beside him. For humans are merely one form among many, which the world produces over and over again.... And death, which I have always regarded as the greatest dimension of life, dark, compelling, was no more than a pipe that springs a leak, a branch that cracks in the wind, a jacket that slips off a clothes hanger and falls to the floor.

We touched earlier on the error—into which many writing on My Struggle have fallen—of seizing on certain passages in isolation. This passage, for instance, needs to be read not only alongside the meditation on death and the bodies of the dead that opens Book One but also in tension with others—for instance, the passage late in Book Two, at the christening of Vanja, the firstborn child of Karl Ove and Linda, his second wife. Karl Ove finds himself taking Communion.

Why had I done it?

Had I become a Christian?

I, a fervent anti-Christian from early teenage years and a materialist in my heart of hearts, had, in one second, without any reflection, got to my feet, walked up the aisle and knelt in front of the altar. It had been pure impulse. And meeting these glares [from family members and friends, who wondered what he was doing], I had no defense. I couldn’t say I was a Christian. I looked down, slightly ashamed.

And yet, he considers, in his writing he “was slowly realizing [what] I wanted to explore: the sacred.” He has been working with biblical texts, “and the gravity, the wild intensity in them, which was never far removed from the sacred, where I had never been or would ever go, yet which I sensed all the same, had made me think differently about Jesus Christ, for it was about flesh and blood, it was about birth and death, and we were linked to it through our bodies and blood, those we beget and those we bury”—and the sentence builds to this: “and the only place I knew where this was formulated, the most extreme yet simplest things, was in these holy scriptures.” In Book Three, we’ll learn that—before his turn away in his early teen years—Karl Ove stood out from the other kids in the housing estate precisely because he was a Christian (a choice that Dad regarded sardonically). It will be interesting to follow this thread through the last three volumes.