The Senate Intelligence Committee’s recent report on the CIA’s discontinued interrogation-and-detention program confirmed what many Americans have long suspected: that public officials at the CIA and in the George W. Bush administration have not been altogether truthful in their accounts of what that program entailed, how many detainees it included, and how useful it was in obtaining actionable intelligence in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks. The full six-thousand-page report remains unavailable to the public, but a five-hundred-page executive summary, released on December 9 by Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), provides damning evidence that the CIA provided inaccurate information about its “enhanced-interrogation techniques” to those charged with oversight of the agency.

For years the CIA’s leadership has claimed that it held only ninety-eight prisoners, but, according to the new report, the CIA’s own records show that 119 men were detained. The report also claims that at least twenty-six of them were “wrongfully held.” Among the innocent detainees was an “intellectually challenged” man held “solely as leverage to get a family member to provide information,” along with two men believed to be connected to Al Qaeda only because of “information fabricated by a CIA detainee subjected to the CIA’s enhanced-interrogation techniques.” In fact, the committee found that much of the information produced by abusive interrogation methods was false and that the rest of it was obtainable by other means. The report concludes that, contrary to the claims of several former White House and CIA officials, enhanced interrogation did not lead to the killing of Osama bin Laden or to the capture of other Al Qaeda leaders. Many of the CIA’s defenders, including the Intelligence Committee’s Republican members, vigorously object to this conclusion, but so far they have failed to refute it.

As for the enhanced-interrogation techniques themselves, the report informs us that they included not only waterboarding—for which the United States prosecuted Japanese soldiers after World War II—but also depriving prisoners of sleep for as long as a week; locking them up in coffin-size “confinement boxes”; keeping them shackled in stress positions for days at a time; threatening to kill their families; holding naked prisoners in cold cells (one innocent detainee died of hypothermia); rectal hydration and feeding, in which CIA officers would pump fluids and mashed-up food into a prisoner’s rectum through a tube; and “rough takedowns,” in which CIA officers “would scream at a detainee, drag him outside of his cell, cut his clothes off, and secure him with Mylar tape” before beating him as he was dragged up and down a long corridor.

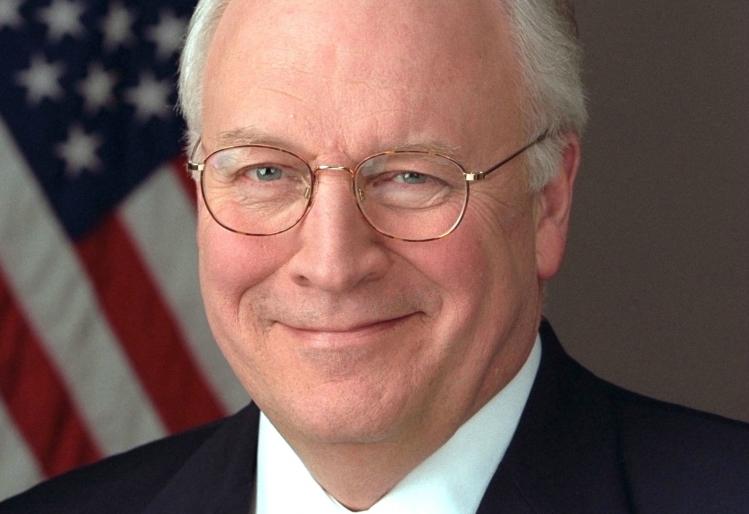

Most people would call this torture. Not former Vice President Dick Cheney, who took to the airwaves to declare the Senate report a “crock” and insisted that the CIA’s methods didn’t amount to torture because they had been “blessed” by the Bush administration’s Department of Justice. Cheney says he believes that rectal hydration was done for “medical reasons” (which is false) but also insists that, because this particular technique never received the DOJ’s blessing, “it wasn’t torture in terms of it wasn’t part of the program.” For Cheney, it would seem, anything declared legal by Justice Department lawyers doesn’t count as torture, while anything not declared legal just doesn’t count. This brazen illogic has won Cheney another round of applause on the Fox News right, which has largely dismissed the Senate report as a partisan stunt.

Worse than Cheney’s logic, though, are his cynicism and shamelessness. Asked on Meet the Press whether it bothered him that 25 percent of the detainees turned out to be innocent, Cheney responded, “I have no problem as long as we achieve our objective.... I’d do it all again in a minute.” Cheney is a man of no regrets and very few scruples. He believes that the end justifies the means. This is, not incidentally, one belief that defenders of torture share with defenders of terrorism.

In the immediate aftermath of the September 11 attacks, many Americans of both parties, moved by either fear or a desire for revenge, were willing to let their government do whatever it took to destroy Al Qaeda. That understandable instinct grew less excusable by the year, as did any confidence in the officials who authorized torture. Among these, Dick Cheney, who also helped scare Americans into believing that Saddam Hussein would give Al Qaeda weapons of mass destruction, has proven to be particularly untrustworthy. In a perfect world, those who authorized such things as waterboarding and confinement boxes would be prosecuted in accordance with the UN Convention against Torture, signed by Ronald Reagan in 1988. In this imperfect world—where it’s not uncommon for the powerful to get away with evil, and where the strict demands of justice are sometimes at odds with political prudence—those who authorized torture should at the very least be shunned or ignored as they try to defend their shameful record. They no longer deserve a respectful hearing.