The nameless narrator of Diary of the Fall believes it is impossible for him to write anything new about the Holocaust: “If there’s one thing the world doesn’t need to hear it’s my thoughts on the subject.” As the grandson of an Auschwitz survivor, however, he is also keenly aware that in “sixty years’ time, it will be very hard to find the son of anyone who was imprisoned in Auschwitz.” It is impossible for him, that is, not to write about the Holocaust.

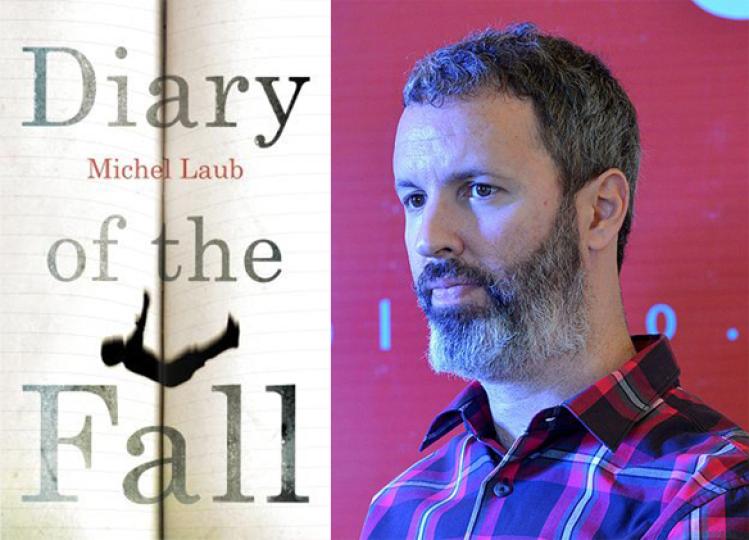

Diary of the Fall is Brazilian novelist Michel Laub’s fifth novel, but the first to appear in English. This seamless translation by Margaret Jull Costa is an intriguing introduction. Laub’s opening expends a good deal of narrative energy avoiding the atrocities of Auschwitz and focusing instead on the atrocities of schoolboys. The narrator recalls his circle of friends, wealthy children at a private Jewish school, throwing a classmate in the air thirteen times at his thirteenth birthday party, their bar mitzvah tradition. This time, however, they don’t catch the boy. João—the only named character in the novel and the only Catholic in their class—is poor and motherless. He has long submitted to the other boys’ torments, but on this occasion, with the narrator “supporting his neck because that’s the most vulnerable part of the body,” but then dropping him, he is seriously injured. In the aftermath, sickened by guilt, the narrator befriends João, as if to make reparations.

Diary of the Fall is an intense contemplation of the ways Auschwitz has marked three generations, but also of the infinite ways humans have found to torment and humiliate each other from an early age. If this does not sound uplifting, be assured that it is compelling. Despite its insistence on the “nonviability of human experience at all times and in all places” in the face of the Holocaust and all the atrocities history records, it unexpectedly asserts the possibility of hope.

Laub’s narrator uses a formal device that frees him from the sentimentalized or heroic post-Holocaust narrative: most of the novel is written in numbered paragraphs. It’s not a new form—J. M. Coetzee and Roberto Bolaño have certainly used it to strong effect—but here it is mesmerizing. Suggesting journal or diary entries, the numbers also imply a compulsive need to order what is objectively disordered: the cruel infliction of suffering. They allow the narrator to cut a subject short when he’s feeling evasive, and to circle back to a motif in a new entry that may be simultaneously repetitive and amplifying. The prose achieves an incantatory effect. The only sections of the book not broken into numbered paragraphs are those “Notes” we readers might expect to be numbered. This is not a humorless book, but what humor it extracts is dry, to say the least.

***

The narrator is now a middle-aged man on his third marriage, which is falling apart as his others have done. As he recounts his past marriages, he must also inevitably record the story of his alcoholism, which begins when he is fourteen—another traumatic year. When João leaves the Jewish school, the narrator follows, against his father’s wishes. Their argument about a Jewish education culminates in an outburst: the adolescent son says he doesn’t “give a toss” about what happened to his grandfather at Auschwitz, and the father, in turn, finally tells the story of his grandfather’s last days and suicide. The revelations allow father and son to enter a period of trucelike silence and even affection, but the friendship between the two boys cannot hold. In their new school, they reverse roles. Subjected to cruel anti-Semitic notes and drawings, the narrator retaliates with a devastating piece of psychological cruelty, betraying João all over again. “One of the things I learned over the years,” he admits, “was never to show any weakness.”

And now, even as he believes he cannot say anything beyond what Primo Levi (whose fatal fall from a staircase landing was also ruled a suicide) and a long list of writers from Bruno Bettelheim to Art Spiegelman have already said about the Holocaust, he presses on. The effects will be felt for generations to come, our narrator makes clear, but so too will the cruelties inflicted by those with family ties to the Holocaust. They will not be able to blame their actions on the Holocaust, but they must still try to puzzle through how it has affected them. The narrator’s third marriage appears as doomed as his first two, until a crisis appears in the form of his father’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis, a fitting narrative invocation of fading memory. Though the novel has depicted multiple falls since the narrator and his schoolmates dropped João, one of the most moving is only a near-fall, when the narrator arrives at his parents’ house to deliver the news of the diagnosis. His mother takes a step back, and in her disorientation and fear her son sees the love that will brace him as he confronts his own future.

Just as there are multiple falls, there are multiple diaries. Throughout the novel, the narrator intersperses his grandfather’s chilling diary entries, whose hyper-realistic definitions of objects become almost surreal. As the father confronts the impending acceleration of his disease, he too begins a diary, far more personal, which he sends piecemeal to the narrator. The narrator himself, we learn, has also constructed this novel as a diary. It is in the final entries that we understand an assertion of hope is indeed being made. It is a daring move. In a novel so relentlessly bleak—so intelligently bleak—the introduction of hope comes almost as a shock: the narrator is able to envision a “past that is…of no importance compared to what I am and will be, forty years old, with everything still before me.” The writer willing to take that existential turn deserves an international presence, and I hope all his novels will be published in English sooner rather than later. Meanwhile, Diary of the Fall will serve as a powerful introduction.