When does history begin? One answer: when an author is born after the events she describes. Mary Ziegler was born in 1982, just at the end of the period she depicts as the “lost” history of Roe v. Wade. Not lost to all of a certain age, perhaps, but her account may surprise even the closest (and oldest) observers of the battles that followed the 1973 Supreme Court decision. Until then, changing abortion law had required a state-by-state effort: thirty states banned abortion while twenty had legalized it within strict limits. The Court’s decision made abortion legal in all fifty states with few restrictions. None of the state-based advocacy organizations, whether pro or con, were prepared for the scope of Roe. Those opposed to legalization couldn’t believe that the Court failed to acknowledge any fetal rights. Those in favor of legalization were pleased: the Court had gone further than they expected.

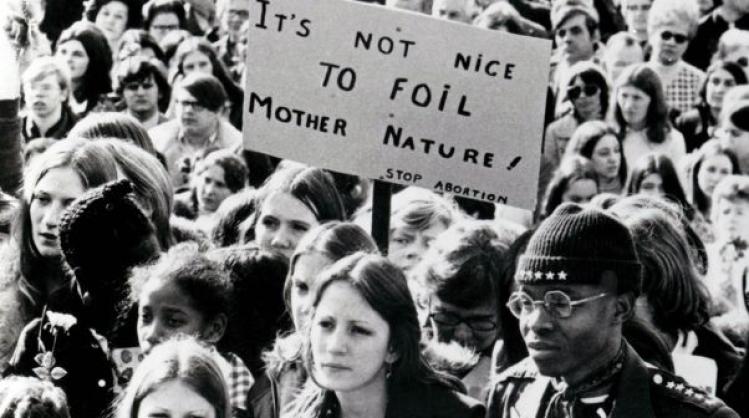

Pro-life groups were quick to organize, while pro-abortion groups (later recast as pro-choice) became complacent, only reacting over time to their opponents’ success in organizing political dissent. Over the next decade, each side went to battle with different strategies and resources; one to overturn Roe, the other to preserve and strengthen it. Ziegler has disinterred this decade, 1973 to 1983, from the archives of these battling groups—correspondence, minutes of meetings and conferences, news stories, newsletters, and press releases—supplemented with the accounts of surviving advocates. This varied and complex story is indeed often “lost” amid today’s entrenched positions.

The pro-life movement began with feminists and anti-feminists alike, those in favor of birth control and those opposed, those who supported a fetal-life amendment and those who did not. Foreseeing that Roe would not soon be overturned, some “incrementalists” turned to legal efforts to restrict the procedure through informed consent, medical regulation, a ban on federal funding, and an end to late-term abortions. “Absolutist” pro-lifers wanted Roe overturned altogether. During the Reagan administration, two versions of a fetal-life amendment emerged in Congress. Both failed. The absolutists later turned to picketing clinics, curbside counseling, and ultimately, for a handful of individuals, attacking physicians and clinic workers, a period that lies beyond Ziegler’s time frame.

The pro-choice movement faced a different kind of sorting out. Before Roe, legalizing abortion was a secondary issue for the population-control movement. The Population Council and its allies, funded by John D. Rockefeller and the Rockefeller Foundation, were concerned with reducing population growth around the world, focusing their efforts on contraception and sterilization. Though pro-abortion groups were well placed to take advantage of those organizational and financial resources, they had to disentangle themselves from the eugenics movement of the nineteenth and early twentieth century, which had become linked with the population-control movement. The taint of race and class prejudice offended many, especially African Americans who had to be convinced that abortion was not a plot to reduce the size of the Black population. Over the decade, the growing importance of feminism for African-American women dampened some, if not all, of these suspicions.

In addition to their internal differences, both sides had to thread their way through a maze of issues that came to be associated with the abortion debate: family values, working mothers, women’s rights, the sexual revolution, and the campaign for an Equal Rights Amendment. Divisions between the two emerged out of disagreements over these issues as well as abortion. Ziegler’s interviews with movement leaders show that there were pro-life women who favored contraception, smaller families, and the women’s movement; some were members of their local Planned Parenthood. As the pro-choice movement grew, a range of opinions emerged. Some members defended family values, shunned the language of population control, and worked to promote effective contraception rather than abortion. Yet even though both camps included members who did not follow a party line, the public debate became dominated by extremists. Each side ultimately aligned itself with Democrats or Republicans, contributing to the partisan divide that persists today. (Yes, Virginia, back in the day many Republicans were pro-abortion; many Democrats were not.)

Ziegler pays particular attention to the mid-1970s alliance of the resource-poor pro-life movement with the well-funded religious right and the Moral Majority. Ziegler makes much of this alliance and its wooing and vetting of Republican politicians. Though she is otherwise evenhanded in her account, Ziegler’s emphasis on the pro-life/Religious Right alliance overshadows the role that Rockefeller and other foundations played in funding and directing prochoice organizations. Donald Critchlow, whose Intended Consequences Ziegler cites, provides a detailed account of the support and direction given by the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations to the pro-choice movement, which parallels the relationship between pro-lifers and the religious right. But Ziegler fails to perceive that the rich and established can be no less political in pursuing their agendas than the pro-life and religious “outsiders”— a curious lapse in her otherwise fair-minded analysis.

Many lay Catholics appear in this story of the pro-life movement. In her 1984 study, Abortion and the Politics of Motherhood, Kristen Luker found that 80 percent of pro-life women activists were Catholic. But Ziegler’s “lost” history barely mentions the U.S. Catholic bishops conference, or any individual bishop. Is that because she didn’t attempt to study the bishops’ actions (no doubt, most of the relevant archives are closed), or because, in fact, the bishops played a far less active role than is often advertised? Perhaps Michael Harrington’s observation that the pro-life movement was one of the great grass-movements of the seventies is confirmed in this history.

In a final chapter, Ziegler surveys the legacy of the issues fought over in this “lost” history. What fueled abortion politics in that decade, she maintains, were battles over women’s rights, family values, gender equality, and sexual liberation. Roe itself, she argues, was far less central. Luker too argued, “While on the surface it is the embryo’s fate that seems to be at stake, the abortion debate is actually about the meaning of women’s lives.” Luker’s conclusion has often been cited by pro-choice advocates who would prefer to “change the subject.” To the extent that Ziegler gives the same impression, it diminishes the importance the pro-life movement attaches to the moral and legal status of the fetus, the very error the Court was seen to make. Even today, that status roils the controversy over harvesting fetal organs for medical research. Ziegler may have a point about references to Roe in these battles. Indeed, critiques of the 1973 decision by the likes of Justices Antonin Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg and legal scholars such as Cass Sunstein, Richard Posner, William Eskridge, and John Ferejohn leave Roe looking far less substantial than it once appeared. Nevertheless, however tattered that decision looks today, it precipitated a political and cultural debate that is far from over—and far from resolved.