Joy Williams’s The Changeling belongs on the same shelf as Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping and Alexander Chee’s Edinburgh—works of visionary genius that are harrowing in the deep, even theological sense. When it was first published in 1978, though, Williams’s novel was, to use Byron’s words about Keats, “snuffed out by an article.”

Anatole Broyard, writing for the New York Times, charged the novel on multiple counts. The plot—an “arbitrary muddle about a young woman who is more or less kidnapped by a man who marries her and takes her to live on an island that is owned by his family”—wasn’t plotty enough for his tastes. The characters were too opaque (the protagonist “is so inert as to seem almost moronic”), the style too turgid, the whole thing a disaster. In Broyard’s snarkily summarizing dismissal, “Only a very talented person could write as badly as Miss Williams does in her second novel.”

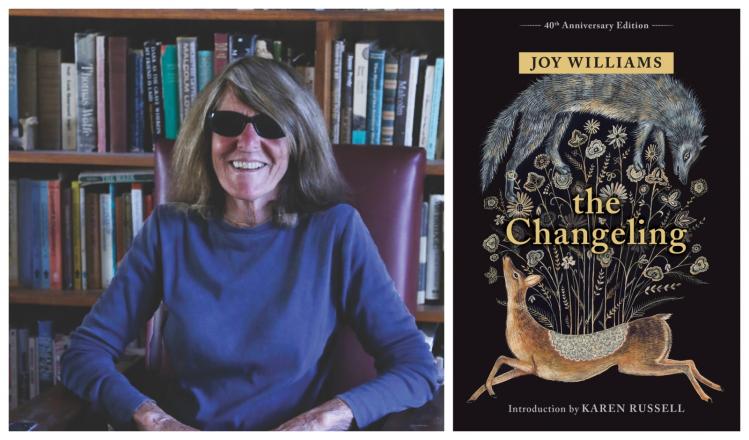

Such a filleting, from such a reputable source, had the effect you might expect. The Changeling quickly went out of print. There it languished until 2008, when it was reissued by the small press Fairy Tale Review. Now, Tin House has brought out a fortieth-anniversary edition, complete with a beautiful cover and an excellent introduction by Karen Russell.

At a certain level, I get Broyard’s criticisms. The novel is fantastically, and often confusingly, plotted. It opens in a crisp, almost hard-boiled tone that suggests we’re about to encounter a lean and propulsive narrative: “There was a young woman sitting in the bar. Her name was Pearl. She was drinking gin and tonics and she held an infant in the crock of her right arm. The infant was two months old and his name was Sam.” We soon learn that Pearl is sitting in this Miami bar after fleeing from the North Atlantic family island that Broyard mentions. Ah, we might think, a story of a mother and child on the lam. Exciting!

Soon, though, this possible narrative short-circuits: Pearl’s husband finds her, and swiftly she’s back on a plane to the island. Then, the plane crashes in the swamp. Pearl’s husband dies but she miraculously survives, as does Sam—though she’s convinced that the “Sam” who has survived is an impostor, a supernatural changeling switched in for her actual son: “There was something peculiar about the baby. He was like an animal. She had a baby now that wasn’t hers.” The descent has begun; it only gets deeper and crazier from here.

Back on the family island, Pearl sees her world begin to fray at the edges, with reality and fantasy becoming hard to distinguish. She drinks more and more—gin primarily, but also white wine, really anything to distract her from the sense that something is off with her would-be son and the world at-large. Pearl’s sinister brother-in-law Thomas, now the patriarch of the family, is also a collector of children, having adopted “all manner of misfits and foundlings,” seeing “each child as an exhilarating beast of transmutative delights” and shaping them to his own designs and wishes. These children overrun the island, playing murderous games and acting in a feral manner, asking questions and speaking in a language that is gnomic, uncanny, disturbed: “Did you know that a dead tree struck by lightning can come back to life?”; “Why do you drink? … Because it makes your bones blossom, isn’t that right, isn’t that what you say Pearl?”; “If you mash up the pituitary glands of a cow and use it for shampoo would all the hairs on your head be able to see?”

These questions—about the dead coming back to life; about the skeletal becoming vegetal; about the animal and the human blurring—show that the children have a precocious sense for the kind of transmutative world in which they live. The island is a realm of transformation, where children are wild and adults are sadistic, where identities shift and transmogrify. We’re less in the world of the novel than in the universe of Shakespeare or Ovid. Humans become animal-like. Eventually, in a moment that Pearl finds both frightening and fascinating, the children seem to morph into actual animals. Transfiguration here isn’t enchanting, it’s terrifying, and Pearl is forced to choose between the world of adults, which is empiricist and reasonable and controlling and hopelessly empty, and the world of children/animals, which is visionary and unreasonable and violently, beautifully full.

If you want a clear narrative or characters who are relatable (that horrible, vacuous word), then you should look elsewhere. But the prose—good lord, the prose. Despite the confusions of plot, there are short bursts of pure lyricism throughout, like this description of light: “The rain covered the glass with artificial night like a dark archangel and then lifted and was gone. The wan light of the interrupted day fell into the room.” And then there are Williams’s moments of exquisite meanness, which demonstrate her ability to capture perfectly those moments when others feel monstrous to us—and when we seem monstrous to ourselves. Looking at a barmaid and her customer, Pearl “imagined them in some rank room after closing hours, spreading dough over their bodies and eating it off in some bourgeois rite.” Looking at herself after she’s just met her soon-to-be husband, Pearl recognizes her longing for oblivion: “She felt as though he were emptying her, right there on the spot, absorbing little parts of her, nullifying them, closing the little exits in her mind. Jesus walked out. The doors kept shutting in her mind. She did not want to interfere.” On a sentence-by-sentence basis, The Changeling is sharp, witty, surprising, unsettling, a perfect mixture of the syntactically disciplined and the imaginatively unhinged.

Then, there’s the novel’s representation of children. I’ll admit it: I’m a sucker for any writer who punctures our culture’s empty pieties about children. I love my nieces and nephews dearly, but they often remind me more of animals than angels. (Augustine knew this, of course.) Even if you’re not as skeptical about the perfections of childhood as I am, how can you not admire, or at least warily assent to, these lines: “Children were quite disturbing really. It was difficult to think about children for long. They were all fickle little nihilists and one was forever being forced to protect oneself from their murderousness.” Just while writing this piece, I witnessed a public meltdown of a child over a refused treat; fickle little nihilist, indeed.

Ultimately, though, what elevates The Changeling to the level of masterpiece is its theological imagination. Just as Williams undermines our Hallmark understanding of childhood, so too she razes any comforting blandishments we might have about religion. In an early passage, Pearl thinks about her milquetoast Christian upbringing:

The few simple beliefs and inherited moralities that she had adopted from her parents were as inadequate guides for her own life as they had been for theirs. Her mother, who was a Baptist, told her that she should not eat cookies in the bathroom because God would not like it. She told her that she should keep the top of her bookcase dusted even though no one could see the top of her bookcase because God would see it and judge her. She told her that she could be interested in the Devil as long as she did not allow the Devil to become interested in her.

As the novel moves forward, the middle-class God of weak prohibitions, one who cares deeply about cleanliness but doesn’t care much about the soul, fades. Pearl feels herself called by something beyond the world of the everyday, but it’s not by her mother’s Baptist God. She knows that her “son” Sam is not right, that he’s inhuman, but she knows that she’s called to love him despite and because of this: “Love for Sam would entail accepting the monstrosity of salvation.”

Why is salvation monstrous for Pearl and for the novel? Because salvation means absolute transformation, and absolute transformation necessarily entails violence. It’s not a matter of clean bookcases but of a harrowed soul; not of following humane dictates but of being pierced and changed by the absolutely Other. Salvation is unnatural and uncivilized, the novel suggests, and anyone who tells you otherwise is lying. Through her experience on the island and with its children, Pearl comes to experience a God that is totally unlike the one she has been led to expect: “Not the God of her mother’s faulty and romantic vision, but the true one. A God of barbaric and unholy appearance, with a mind uncomplimentary to human consciousness.” By the end of the novel, she has come to know “the lunatic face of God.”

You know who knows the lunatic face of God from the beginning, though? The children. Children aren’t angels but beasts, Williams suggests—and it’s precisely in their beastly wildness that they know the divine wildness of God. This novel’s God is a God of the raw, not the cooked.

Jesus said, “Verily I say unto you, Except ye be converted, and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.” The Changeling says yes, absolutely, but don’t think that these words mean we must become innocent, or meek, or gentle, or carefree. They mean, rather, that we must become wild. “Always it was summer in the womanish, childish, animal houseshape of God.” Difficult words to understand, even more difficult words to accept. But that’s the radical message of The Changeling—one that 1978 wasn’t ready to hear, and one that I doubt we’re ready to hear now, either.

The Changeling

40th Anniversary Edition

Joy Williams

Tin House Books; $19.95; 336 pages