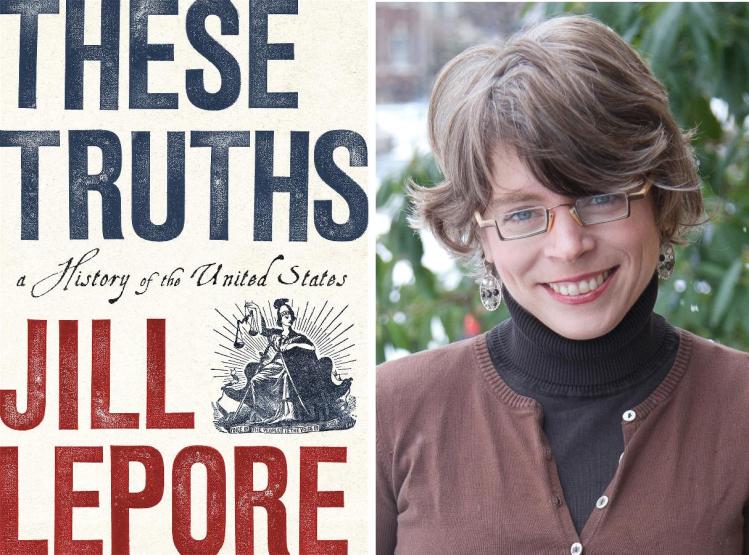

“This book,” explains Jill Lepore in the introduction to her exhilarating one-volume history of the United States, “is meant to double as an old-fashioned civics book.” It’s not a conventional advertisement, but we could do worse than to press a copy of These Truths into the hands of every bored high-school sophomore peeking at Instagram during government class, or every immigrant hoping to obtain citizenship. One of the country’s most accomplished historians, Lepore teaches at Harvard and has written books on topics as diverse as Benjamin Franklin’s underappreciated sister, Jane; the seventeenth-century King Philip’s War in colonial New England; and the origins of Wonder Woman, the comic-book heroine. She has even coauthored a novel—and all this while producing a stream of crisp, witty essays as a staff writer at the New Yorker. In a recent interview, Lepore expressed frustration with encomiums to her productivity, likening them to “complimenting a girl on her personality.” Well, okay. But her output over two decades does inspire awe.

At the outset of These Truths, Lepore warns her readers that the task of fitting the history of the United States into one volume requires hard choices. My own deformation as a professional historian made me flinch when she glided by the Pacific theater in World War II in a paragraph, while spending a couple of pages on the relatively obscure wartime Office of Facts and Figures. Her assessment of the economic boom of the 1950s and ’60s—a few disjointed paragraphs—is insufficient. And Commonweal readers may find the unreflective treatment of Catholics (constituted by Fr. Coughlin, Phyllis Schlafly, and malevolent opponents of Roe v. Wade) discouraging.

But to focus on the inevitable quibbles is to miss Lepore’s achievement. These Truths is at once a compelling narrative and an argument about American democracy, and in making that argument, it keeps one eye focused on our democracy’s unstable present. If the initial two chapters, taking us from Christopher Columbus up to the American Revolution, are the least compelling, that’s because for Lepore the real story is yet to begin. Only with the Declaration of Independence and its self-evident truths, followed eleven years later by the Constitution and its effort of “securing the blessings of liberty,” does American history succeed in fashioning a template for an ongoing argument about equality, natural rights, and the sovereignty of the people.

The ricochets of these arguments structure Lepore’s book. The most consequential is the relationship between slavery and the “unalienable” right to life, liberty, and happiness—a phrase coined by Thomas Jefferson a few years before he fathered the first of six children with his enslaved lover, Sally Hemings. Such paradoxes abound. The first New York newspaper to include a printed copy of Alexander Hamilton’s The Federalist No. 1, Lepore tells us, also contained a classified ad offering for sale a “A LIKELY young NEGRO WENCH,” touting her as “healthy” and “remarkably handy at housework.”

Lepore deftly sketches the protagonists in the enduring debate over slavery, beginning at the constitutional convention in Philadelphia and continuing into the middle of the nineteenth century. The cast includes James Madison; abolitionists David Walker and William Lloyd Garrison; John Brown; John Calhoun; Abraham Lincoln and his political rival, Stephen Douglas; and above all, Frederick Douglass.

The first half of These Truths is organized as much around Douglass as any other figure. The world’s most famous person of African descent, the most photographed person of the nineteenth century (for Lepore, photography is the “technology of democracy”), and the most celebrated American memoirist since Benjamin Franklin, Douglass did more than anyone to demonstrate the inhumanity of the slave system he himself had escaped. His 1852 denunciation of slavery, conspicuously delivered the day after the Fourth of July, excoriated the “boasted liberty” of the United States as a shameful blend of “bombast, fraud, deception, impiety and hypocrisy.”

After the Civil War, Douglass fought for civic equality for freed slaves. He favored the vote for women, too, even if he angered feminist allies by not pressing the issue when Congress approved the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, granting voting rights to all men—but not women—regardless of “race, color or previous condition of servitude.” He lived to see white southern (and some northern) politicians successfully evade the spirit of the Reconstruction-era amendments. By the early twentieth century, just a decade after Douglass’s death, slavery had long been vanquished but it had also become illegal for a black child to play checkers with a white child in a Birmingham public park.

The pace of These Truths accelerates once Lepore reaches the 1930s, an era she interprets as the beginning of a slow unraveling of the founders’ commitment to discovering truth, yielding devastating effects for democracy. Her view that the advent of polling firms (the most famous led by George Gallup) and political consulting partnerships formed the “single most important force in American democracy” since the creation of political parties might seem implausible. Yet campaigns organized around polling data, and reliant on experts paid to fashion candidates acceptable to the public—and on voters conditioned to mistake polling data for reality—surely did weaken the process by which parties choose political candidates. So-called public opinion, Edward R. Murrow warned in 1952, should not become a “petty tyranny” dictating voters’ views of the candidates. Radio, too, proved a destabilizing political medium, one beyond the control of political parties. Yes, radio delivered Franklin Roosevelt’s heartwarming fireside chats. But Lepore dwells on more ambiguous accomplishments, such as its success in making Christian fundamentalism a national movement, and its appeal to demagogues such as Fr. Coughlin and Huey Long—or, more darkly, to fascist propagandists such as Joseph Goebbels.

Much as he stalked Hillary Clinton onstage during the 2016 presidential debates, Donald Trump looms in the background during Lepore’s coverage of the period since the 1950s. The moral urgency of Martin Luther King Jr. occupies its rightful place in this part of the story, as do the charisma of John Kennedy and the crisis in Vietnam. The origins of our current partisanship are evident too. The divide began with the political parties, and Lepore has fun with a report from the American Political Science Association in 1950 bemoaning the absence—yes, the absence—of partisanship in American life. A decade later, Barry Goldwater offered a conservative choice (not an echo), and soon after that, the Democratic Party began its move to the left on social issues. Over time, politicians with the capacity to work across party lines, especially moderate Democrats and Republicans (think Jimmy Carter and Nelson Rockefeller) became endangered species.

Bill Clinton, a centrist Democrat, would seem an exception; but here Lepore is herself immoderate. Clinton in her view is “a rascal,” and his effort to reform welfare policy, his support of NAFTA, and his endorsement of the federal crime bill of 1994 cumulatively marked an “abdication of the New Deal.” These judgments are severe, especially given that Lepore concedes there were precedents for these actions, and also notes that incomes during and after the Clinton era “rose across the board.” Surely Clinton’s participation in welfare reform made it better than it otherwise would have been—and it is worth noting that in urging what now seem like horribly misguided sentencing guidelines, he was joined by members of the Congressional Black Caucus. On the other side of the ledger, and in support of Lepore’s claim, Clinton and his treasury secretary, Larry Summers, unleashed investment banks from New Deal restrictions, helping enable the financial malfeasance that sparked the 2008 recession and, with it, a search for new political champions by the disaffected rural white working class.

Lepore’s appraisal of Clinton’s “foolishness, irresponsibility and recklessness” in his affair with Monica Lewinsky—a twenty-one-year-old intern, Lepore reminds us—also hits its mark. The affair has had lasting consequences. Its exploitation by Republicans began a bipartisan pattern of attempting to discredit and even unseat presidents, including George W. Bush and Barack Obama. It also pushed further into the national spotlight a New York real-estate developer and twice-divorced socialite, Donald Trump, whose loud and gleeful opinions included the assertion that he would have respected Clinton more if he’d had an affair with a supermodel. Trump moved on to jumpstarting the “birther” movement that slandered and denigrated President Obama, contributing to a political polarization so widespread that by 2018, 40 percent of Americans said they would be “upset” with a son or daughter marrying a member of another political party.

Lepore’s treatment of the Clinton scandal also lays bare the roots of the media fragmentation that plagues us today. The ratings of an upstart network, Fox, skyrocketed with saturation coverage of the Lewinsky episode. Once broadly nonpartisan, and indeed required by the government to give “equal time” to mainstream candidates and viewpoints, major media outlets lost viewers and listeners to more combative competitors. Conservative talk radio (some nine hundred stations by 1992, led by the influential Rush Limbaugh) and Fox News made no pretense of objectivity, with Limbaugh once going so far as to accuse Hillary Clinton of concealing a murder. Donald Trump’s attacks on reporters, These Truths reminds us, are the culmination of a decades-long effort to discredit the “mainstream media.” The liberal reaction has been more of the same, just less ruthless; MSNBC in Lepore’s view is not “less partisan than Fox News...merely differently partisan.” The most dramatic assault on objectivity occurred in 2016, when Russian hackers manipulated Facebook to place ads extolling Donald Trump and denigrating Hillary Clinton before 120 million Americans.

Along with political parties and the media, universities have contributed to the polarization problem, and currently find themselves teetering on the edge of what Lepore terms an “epistemological abyss.” Here the culprits are mostly on the left, and Lepore is cold-eyed, even courageous, in her assessment of an identity politics, traceable to the 1960s and ’70s, that too often seems more concerned with the social location of the speaker than the content of her ideas, and that has effectively dismissed the idea of “truth” as old-fashioned, even malign. Just as liberals followed conservatives in developing their own media outlets, conservatives eventually took to identity politics, too, under the veneer of “fair and balanced” straight talk, with groups such as the National Rifle Association cultivating what Lepore calls a no-compromise “cultural style animated by indictment and indignation.” She is especially good on how climate change has gotten dismissed as “fake news,” and described as merely one theory among many, by Republicans who know better. These Truths makes clear that the new and daunting environmental reality we face today should dampen our willingness to dismiss ideals of objectivity. A “post-truth” view of science seems less appealing in a world where icebergs the size of Delaware are breaking off Antarctica.

A reader might skip the final sentences of These Truths and their extended metaphor about a reeling ship of state, with liberals stuck belowdecks and conservatives setting bonfires with the planks. Better to finish with Lepore’s sober-minded reporting on a 2016 post-election forum held at Harvard, where representatives from Facebook, major media outlets, and the campaigns all seemed singularly uninterested in how their own mistakes might have brought them (and us) to this point. Better still to remember her eloquent plea to revisit the nation’s founding truths, notably a commitment to equality and popular sovereignty informed by debate and inquiry. Displayed to great effect as recently as the civil-rights struggle of the 1960s, this commitment badly needs renewal. So too does the sense that the United States remains a noble experiment in rule of, by, and for the people.

The renewal must take place on both sides of the ideological divide. Liberals, Lepore writes, need to rely less on “judicial remedies, political theater and purity crusades.” Conservatives need to avoid overzealous judicial remedies, too, and refrain from wallowing in false nostalgia about lapsed American greatness. Good advice all around, especially at a moment when democracies around the world are experiencing their own varieties of populist nationalism. Let’s hope These Truths finds the readership it deserves—and pushes us toward the politics we need.

These Truths

A History of the United States

Jill Lepore

W. W. Norton, $39.95, 960 pp.