Echo in the Canyon refers to a hilly Los Angeles neighborhood whose winding roads link Sunset Boulevard to the San Fernando Valley, and whose population in the mid-1960s included key figures in the emerging pop-folk-rock scene. Laurel Canyon was a place, says David Crosby, then of the Byrds, where you could be close to a city yet feel out in the country; where instead of clubs, people popped into each other’s homes for impromptu music sessions, trading ideas and inspiration. The community provided crucial proximity to the burgeoning music industry in LA, which was wresting influence from New York and increasingly provided a conduit to record deals and airplay. Suddenly, careers were taking off. “We knew the Byrds,” Michelle Phillips of The Mamas and the Papas recalls with a laugh. “They were our friends. If they had a hit record, anyone could have one!” The scene was the pop-music equivalent, the film proposes, to the literary ferment of Paris in the 1920s and ’30s.

Directed by longtime music executive Andrew Slater, and featuring Jakob Dylan as a kind of master of ceremonies, the documentary studies the transformative energies of the LA music scene during those years. Echo interviews many of the chief players from that time and place, along with younger musicians, including Beck, Regina Spektor, Cat Power, and Norah Jones, who ponder the era’s significance, discuss its music, and perform some of the songs in a Laurel Canyon tribute concert.

The transformation that occurred when folk music met the electric guitar is often traced to Bob Dylan and the 1965 Newport Jazz Festival (a subject about which, along with anything else to do with his father, Jakob Dylan is notably silent). But Echo attributes it to Southern California. The theme is announced explicitly by The Mamas and the Papas’ smash hit, “California Dreamin’,” which redirects our attention from the brown leaves and gray sky of Manhattan to the warm and sunny left coast. Musically, the shift is nicely encapsulated in Echo by a segue from Pete Seeger performing “The Bells of Rhymney” before a silent churchlike audience of folk devotees, to the Byrds doing their version of the same song, the austere melody enlivened by Roger McGuinn’s jangling guitar riff on his twelve-string Rickenbacker.

With such deft studies, Echo makes us present at the creation of folk rock. It focuses particularly on the four B’s: the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield, and the Beach Boys, all acting partly in response to the Beatles. The process involved what both Stephen Stills and Ringo Starr refer to as “cross-pollination,” especially across the Atlantic—the way in which the Byrds’ recording of “Mr. Tambourine Man,” for instance, influenced Rubber Soul, and then (via Brian Wilson, who was wowed by it), Pet Sounds—which, lobbed back into the Beatles’ court, in turn helped shape the huge smash of Sgt. Pepper. It was the kind of musical borrowing that stops short of stealing. For instance, George Harrison’s 1965 Rubber Soul song “If I Needed Someone” owes a huge debt to McGuinn’s version of “The Bells of Rhymney”—first recorded, as we have seen, by Seeger, with lyrics taken from a poem written by the Welsh poet Idris Davies way back in 1938, but which McGuinn first heard in a haunting cover by Judy Collins. Given such a complex pedigree, McGuinn wasn’t bothered when a notably similar guitar sequence emerged in the Beatles’ song. Besides, when the song came out, Harrison politely sent McGuinn a note of thanks. People were nicer then.

As for the Beach Boys, they and their trademark surfer pop—garage-band rock-and-roll adorned with mellifluous vocals—might at first glance seem like an outlier in this company. Interviewed by Jakob Dylan, Jackson Browne comments wryly that “To me, at first, The Beach Boys was just four guys wearing the same striped shirt and carrying a surfboard. I thought it was lame.” Then he listened to Pet Sounds and changed his mind. With its innovative and complex orchestrations, and its norm-busting song lengths, Pet Sounds figures as a leitmotif of genius in Echo, drawing lavish comparisons (Bach, Mozart), and a broadly shared awe at Wilson’s gifts as a composer; in the estimation of just about everyone interviewed here, it was the most powerfully influential album of its era.

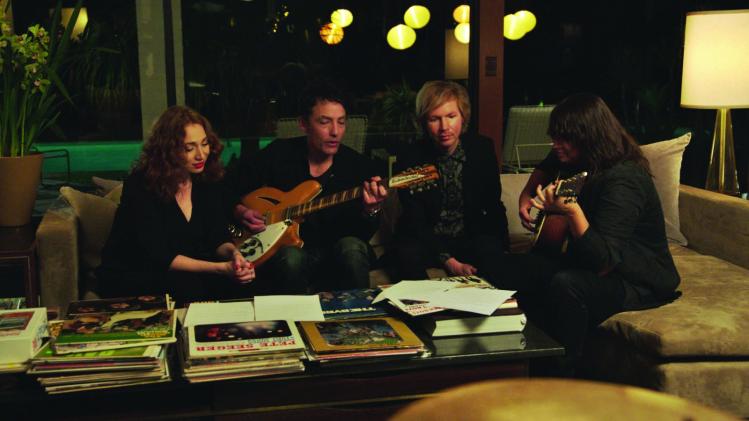

Echo in the Canyon exudes a leisurely nostalgia, and has a low-key, wandering quality. Outtakes from the 1968 film Model Shop, French director Jacques Demy’s love song to LA, are intercut with scenes of Jakob Dylan visiting old recording studios, and Dylan and pals sitting around in someone’s living room, browsing through a big pile of records, discussing album covers, extolling the glories of their musical forebears. The film is oddly constructed so that while Dylan appears to be interviewing people, more often than not, we don’t get to hear his questions, only their answers—as Dylan nods sagely and is quietly impressed. It’s fascinating; at fifty (!) Jakob Dylan strongly resembles his father, yet he possesses all the conventional social and conversational graces that Bob Dylan long ago spurned, if he ever had them. There’s not a touch of anything cryptic or snarky to Dylan fils; he’s a genial host—he’s so normal!—and does a fine job on vocals with many of the songs, especially “I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times” from Pet Sounds.

Curiously, while Crosby, Stills, and Graham Nash all contribute lengthy interviews, Neil Young is absent, until the closing credits, where he is shown—not back then, but today—alone in a studio, playing an odd, stomping version of “Expecting to Fly,” the dreamy 1968 Buffalo Springfield song (and Young composition) that Stills, looking back, describes as a de facto announcement of Young’s leaving the band. Echo construes the song as a signpost of a new and psychedelic impulse in pop music, one that effectively puts an end to the folk-rock moment the film so enjoyably captures.

Danny Boyle’s latest film addresses the meaning and impact of that fourth and greatest B of the ’60s pop scene—the Liverpuddlian one. Yesterday presents a curious mishmash of The Twilight Zone, Notting Hill, and such pop-driven romantic comedies as Once and Begin Again. Rod Serling would have loved the film’s premise (major spoiler coming): What if a strange cosmic hiccup erased the entire history of a world-famous pop group, and for some reason only one man was left with the knowledge of its existence?

This is the conundrum confronting Jack Malik (Himesh Patel), a failed London singer-songwriter who suffers a bicycle accident at the precise moment that a twelve-second global blackout occurs. Jack awakes in a hospital, with minor injuries; consoled by his loyal longtime manager and would-be girlfriend, Ellie (Lily James), Jack asks her, with appreciative playfulness, “Will you still need me, will you still feed me when I’m sixty-four?”

“Why sixty-four?” she asks, puzzled.

Such puzzlement is what you get when you go around quoting the Beatles in a world where the Beatles never existed. As Jack begins to comprehend, some glitch in the cosmic brain, some ontological mini-stroke, has wiped out a seemingly random handful of cultural realities. No more Coca-Cola, no cigarettes, no Harry Potter. And no Beatles.

The situation presents Jack with an opportunity and a dilemma. The opportunity is to reinvigorate his flagging music career with an injection of Lennon and McCartney. The dilemma—which sharpens as his successes mount—is whether doing this is, you know, ethical. Yesterday’s enticing counterfactual provides some prime comic moments. We smile to see the formerly lethargic Jack in his room at his parents’ home, frantically trying to recall the chords and lyrics to all Beatles titles, listed on his wall on colored post-it notes. Soon he is trying out the songs on his friends—who, accustomed to greeting Jack’s music with cheerful affection, are blown away, and bewildered, by his new stuff. Where did this explosion of creativity come from? Working his way outward from friends and family, Jack parlays his ventriloquism into stardom. Soon, failure to launch has become global launch.

Rarely has a film been so wholly and clearly the mingling, for better and for worse, of two very different creative imaginations—belonging to two men who coincidentally were born two weeks apart from one another in 1956. One is Boyle, whose penchant for rousing uplift (along with Slumdog Millionaire, he interestingly also created Isles of Wonder, the opening spectacle of the 2012 London Olympic Games) belies both a minor strain of sci-fi darkness, exemplified in his 2000 post-apocalypse horror film 28 Days, and a sympathy for suffering protagonists (127 Hours). The other is screenwriter Richard Curtis. Curtis has written and directed an array of hit romantic comedies, such pleasantly gossamer-like fluff as Four Weddings and a Funeral, Bridget Jones’s Diary, Notting Hill, and Love Actually.

Yesterday is an agreeable patchwork of a movie, stitched together from pieces of other agreeable movies. A scene in which Jack, by now hailed as a musical genius, is challenged by pop star Ed Sheeran (acting as himself) to a songwriting competition—who can write the better song in ten minutes?—echoes the byplay between Mozart and Salieri in Amadeus. Boyle and Curtis crib a lot from Notting Hill, especially the theme of fame colliding with Everyman normalcy, and, eventually, the soothing and anodyne idea that being truly in love—that recognizing soul-mateness and hewing adamantly to it—is a form of courage, and that this courage is both necessary and sufficient to living right. Can you say “happy ending”? There is even a large, comically oafish, “lovable” character who replicates the role played so memorably by Rhys Ifans in Notting Hill. Much of the film is cozily familiar, including such shtick as the LA-based agent played by Kate McKinnon: watching her bluster and insult her way through the film, a veritable demon of greed, is the definition of a cinematic guilty pleasure.

Once the basic premise of the film is in place, it’s not clear that Boyle and Curtis know quite what to do with it. There are plenty of funny tossed-off ironies; asked to explain his songwriting process, Jack engages in squirrely evasions, finally blurting out that the songs just come to him—“almost like someone else wrote them, you know?” Yuk, yuk. For anyone of the Beatles’ generation, it is also satisfying to see dramatic proof that such masterpieces as “The Long and Winding Road” and “Yesterday” (amusingly, Jack has a hard time with “Eleanor Rigby,” struggling to recall the lyrics) are indeed timeless works of genius—so brilliant, in fact, that a schlubby second-generation Indian man in London can become world famous by singing them. Jack’s fame is the ultimate vindication of Lennon and McCartney.

But what is Jack himself supposed to make of that fame? Should he enjoy it? The most interesting and affecting parts of the movie address his growing turmoil as the songs catapult him to dazzling celebrity. Trapped in a sense of personal fraudulence, and increasingly miserable, he belts out a ferociously unhappy performance, in a huge concert accompanying his breakout album, of “Help!”—ending the song with a ragged cry of desperation, as the audience goes wild. Yet if in fact Jack is to renounce the spurious fame that performing the Beatles brings—if that renunciation is the key to wholeness—we are left with a question: What about the Beatles’ music? Should it be sacrificed on the altar of Jack’s integrity? He is, in effect, the only anthropologist in the world with access to what constitutes, in pop-musical terms, the greatest ancient civilizational dig ever. If he walks away, what about the rest of us?

The last third of Yesterday goes downhill, picking up romantic speed as it zooms along to the inevitable Richard Curtis ending, with Jack abandoning celebrity in order to ally himself with that special person who was there by his side all along—the prospect of pure love tying things together in a joyous vision of life in which, as the Bard wrote, Every Jack shall have his Jill, and all shall be well. The hallmark of such endings is not just that the main thing has to end happily, but that everything does. Thus, as in John Carney’s Begin Again, a musician proves not only happy in love, but defies the evil record-label corporate types by giving his music away as a free download in order to make all humanity happy. But wait, isn’t that the kind of thing that destroyed the music industry? Never mind.

Such quandaries aside, we can be grateful to Boyle and Curtis for any number of pleasures along the way, including gratifying every person’s Walter Mitty pop-music fantasy. Wait, you mean you haven’t heard of Walter Mitty? Hey—what’s going on here?