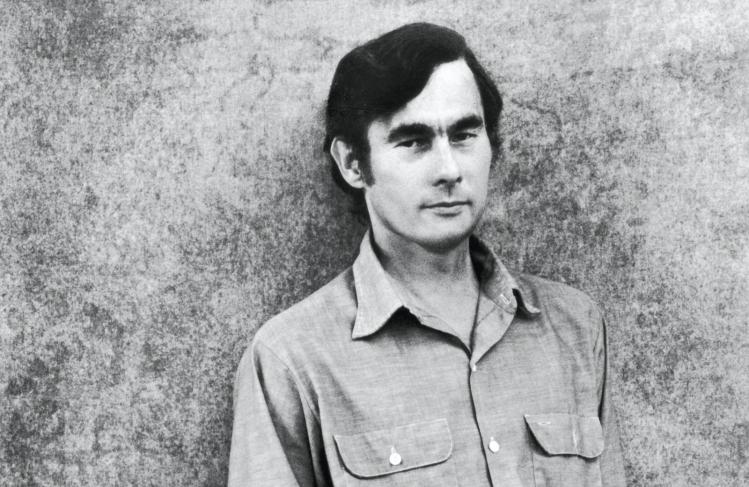

“Theodore Roszak, ’60s Expert, Dies at 77,” read the headline of a New York Times obituary on July 11, 2011. Reducing Roszak’s life and career to digestible nuggets of cliché, the article might as well have dismissed him as a “’60s Period Piece.” As the author of The Making of a Counter Culture (1969) and The Making of an Elder Culture (2009), Roszak, the obit implied, had been a maven of radicals and hippies. Though not quite a Boomer himself (he was well past thirty when he wrote his bestselling anatomy of the counterculture), he acted, the obit explained, as an avid “cheerleader” for cultural upheaval. Tracing the arc of the Boomers from campus rebellion to retirement and senescence, Roszak had “chronicled a generation’s journey from hippies to hip replacement.”

This portrayal of Roszak as a bard of the Boomers ratified the popular memory of “the Sixties,” in which the “counterculture” figured as a carnivalesque insurrection of the id against the military-industrial superego. Punctuated by the iconic milestones—the 1966 Trips Festival, the 1967 Summer of Love, and Woodstock, all conjured to a score of Donovan, Hendrix, or Jefferson Airplane—this story hasn’t changed much in half a century. Seeking release from suburban conformity, repression, and blandness, thousands if not millions of Boomers instigated a moral andcultural revolution, a jubilee of sense and sensibility unprecedented in American history: rock music, the drug culture, sartorial flamboyance, experiments in communal living, the liberation of sexual behavior from the traditional constraints of marriage and propriety. The counterculture flouted the interdictions on desire that made Americans so inhibited and hypocritical. Hippies refused to run in the desperate rat race through the corporate labyrinth, preferring to work (if they worked at all) on organic homesteads or in handicraft cooperatives. They rejected the religion of their parents as so much stolid Judeo-Christian sanctimony, finding more spiritual depth and fulfillment in Zen Buddhism or Gestalt therapy. Against a bourgeois utopia of consumer domesticity—automobiles, ranch houses, canned goods, and patio furniture, all blessed by God in His heaven as long as the mortgage payments were on time—the counterculture posed a paradise of festivity and pleasure enveloped in mysticism.

For many, this account is a celebratory tale of emancipation and pluralism: the countercultural revolution in manners and morals cleared space for feminism, ecological sensitivity, and sexual liberation. Of course, the custodians of traditional mores take the opposite line: the counterculture was a sexual and hallucinogenic pandemonium that prefigured our decadence, undermining marriage, family, work, and faith. To historians, the hippies, beatniks, and flower children were more reformers than revolutionaries, conducting unpaid, pioneering research in the cultural laboratory of capitalism. With their moral and stylistic revolt co-opted and even anticipated by admen, they danced as the barefoot prototypes for today’s bourgeois bohemians. As Thomas Frank writes, the counterculture was “a stage in the development of the values of the American middle class, a colorful installment in the twentieth-century drama of consumer subjectivity.”

Theodore Roszak predicted this ironic denouement, but he also saw something more valuable in the counterculture. In The Making of a Counter Culture and Where the Wasteland Ends (1972), Roszak argued that the cultural ferment of his day was nothing less than a critique of modernity, a challenge to “the myth of objective consciousness,” which reduced the world to the parameters of scientific and technological rationality. In Roszak’s view, the culture that needed to be countered was much broader and more insidious than that of white suburbia. Whether pursued under capitalist or socialist auspices, the whole project of “enlightenment” and mastery threatened to impoverish and obliterate humanity as well as poison and desecrate the planet. Politics had been corrupted by a secular inhumanism oblivious to anything but productivity; it would need to be re-grounded in a beatific longing for a “new heaven and a new earth”—a world transformed by some transcendent power, usually understood as love. Rooted in his own spiritual turmoil, Roszak’s work was far more than an apologia for the ’60s counterculture. It constitutes one of the era’s most impassioned attempts to revitalize the utopian imagination.

Roszak was born in Chicago on November 15, 1933, into a working-class, Roman Catholic family. In search of work, his father, a carpenter, moved them to Los Angeles when Roszak was a child. Always struggling to make money, Roszak’s father died at the age of forty-seven, one of those countless workers who “grind their substance away at hard and dirty work for too little pay and appreciation,” as Roszak later wrote. Determined to avoid a similar fate, Roszak enrolled at UCLA, where he majored and excelled in history. He then pursued doctoral study at Princeton, where he finished in 1958 with a dissertation on Thomas Cromwell and the Henrician Reformation. (He never published it or even returned to the topic.) Roszak seemed destined for a sterling academic career; but for the next five years, his curriculum vitae was desultory: he taught at Stanford, the University of British Columbia, and San Francisco State University before settling at California State at Hayward, where he remained until he retired in 1998.

Along with his professional itinerancy, Roszak wrestled with unfulfilled longings that survived the death of his Catholic faith. Unlike his contemporary Garry Wills—who, in Bare Ruined Choirs (1972), remembered the Catholic parish of his youth as “a ghetto, but not a bad ghetto to grow up in”—Roszak recalled little of his own Catholic boyhood but “shame and dread.” Priests engaged in “ruthless creed mongering,” forcing Roszak to read the Baltimore Catechism, “a jackbooted parade of lifeless verbal formulas.” Inducing anxiety and guilt, penance was little more than “a humiliating and wholly trivial exercise in self-condemnation.” Stuck in this spiritual dungeon, an adolescent Roszak waged “mind-murdering struggles” to protect and unfetter his soul. At UCLA, he “learned the death of God like a data point in freshman survey courses,” and he quickly surmised that secularism was the only respectable position among intellectuals. Among educated people, one didn’t speak of anything so maudlin and retrograde as “the needs of the spirit.” Yet despite God’s consignment to historical oblivion, Roszak longed for something beyond: “the transcendental impulse that cried out in me for life...had to stay jailed up in my mind as a personal fantasy.” Though happy to be free of his clerical tormentors, he now felt imprisoned by atheism.

Roszak grappled with his spiritual ambivalence during a period of two congruent historical trends: the emergence of what historians have called a “post-materialist” political outlook among liberals and socialists, and the halcyon days of the Cold War university, flush with students, talent, and money. The “golden age of capitalism” in the three decades after World War II engendered a new and often buoyant optimism among reformers and radicals throughout the North Atlantic democracies. Thanks to industrial and cybernetic technologies, so the thinking went, advanced capitalist societies had crossed the economic threshold that separated scarcity from abundance. That meant they were now free to cast off the strictures of frugality. Exponentially expanding prosperity permitted the use of economic planning to eradicate poverty, extend the range of public services, and mitigate or abolish the business cycle. Though crystallized in Keynesian economics and public policy, the post-materialist political vision encompassed more than the Great Society programs of President Lyndon B. Johnson. Across the liberal-left spectrum, the impending disappearance of scarcity provoked speculation about new moral and existential possibilities: the reduction of work, the rehabilitation of leisure, the relaxation of sexual restraints and taboos, the cultivation of humanity as an end in itself rather than as a means to greater productivity. As the sociologist David Riesman declared in 1953, “we have approached the accomplishment of one mission, and are searching for another.” In the Port Huron Statement, the 1962 manifesto of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), Tom Hayden declared that the material plenitude generated by automation would finally allow men and women to explore their “unrealized potential for self-cultivation, self-direction, self-understanding, and creativity.” By the end of the 1960s, the Frankfurt School Marxist Herbert Marcuse was proclaiming in An Essay on Liberation (1969) that “utopian possibilities are inherent in the technical and technological forces of advanced capitalism,” and that it is only “their use and restriction in the repressive society which makes them into vehicles of domination.”

The university was to train the intellectual vanguard of a post-materialist society; yet it was also the university that showcased the tensions and contradictions of the liberal imagination. University presidents such as James B. Conant of Harvard and Clark Kerr of UC Berkeley lauded what Kerr called the “multiversity”: higher education as service provider to advanced industrial societies, training the managerial, professional, and technical cadres of the Organization. While liberal academics hoped to imbue the Organization Man with post-materialist values, savants of what the liberal economist John Kenneth Galbraith called “the technostructure”—scientists, engineers, and technicians—forged links with the national-security state, conducting research and development sponsored by the U.S. weapons and surveillance apparatus.

The multiversity also reflected what the sociologist Daniel Bell dubbed “the end of ideology”: the translation of political conflicts into problems soluble by trained professionals. As President John F. Kennedy put it in 1962, “most of the problems that we now face...are technical problems, are administrative problems. They are very sophisticated judgments which do not lend themselves to the great sort of passionate movements which have stirred this country so often in the past.” There was no longer any need for the prophets or visionaries so often included in the canon of the humanities. Although Bell and other liberals believed that “the end of ideology” heralded more rational, humane approaches to public policy, its technocratic implications were not just undemocratic but morally bizarre. Under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara prosecuted the Vietnam War in much the same way that he’d managed the Ford Motor Company: it was all about an efficient administration of resources, with “body counts” and “kill ratios” measuring the output of napalmed, bullet-riddled flesh. “Defense intellectuals” such as Herman Kahn prided themselves on “thinking the unthinkable,” contemplating the thermonuclear incineration of millions with sociopathic equanimity.

While many humanists quietly acquiesced in the ascendency of their better-funded colleagues in the sciences, Roszak raged that the multiversity was a grotesque travesty of intellectual life. In a June 1961 article for the Nation, he scolded academic scientists and engineers for abandoning the university’s traditional mission for a mess of military-industrial pottage. While these experts justified their participation in the development of Titan and Polaris missiles by invoking “the grand romance of scientific progress,” Roszak denounced academic munitions makers for “prostituting to such demonic purposes the nobility of pure intellectual aspiration.” Against their respectable lunacy, he posed figures such as Franz Jägerstätter, the Austrian Catholic who was executed for refusing to serve in the Nazi army (see page 58). Lacking any intellectual sophistication, this “overly pious, strait-laced...colorless, uncomplicated and naïve” man nonetheless “recognized deceit, barbarism, and bloody murder for what they were.” Although his neighbors remembered Jägerstätter as “a zealot, a fanatic, a demented fool,” Roszak thought it was the neighbors who needed to be explained. Like the military-industrial intelligentsia, they were “realistic” and “practical” people who imperturbably rationalized homicide.

The health of Roszak’s “transcendental impulse” also explains why, in the fall of 1964, he began a year-long sabbatical from Hayward. Rather than use this time to finish a book or churn out academic articles, Roszak (accompanied by his wife Betty and their young daughter) went to London to edit Peace News, a renowned British pacifist journal. Though dismissed by one Marxist writer as “a vegetarian tabloid with a Quaker emphasis,” Peace News had had an illustrious roster of contributors since its founding in 1937: Vera Brittain, George Lansbury, A. J. Muste, Richard Gregg, Alex Comfort (yes, that Alex Comfort), Kenneth Kaunda, and Kwame Nkrumah. Alas, Roszak found working with the British peace movement a bleak and dispiriting experience. British pacifists, like their U.S. counterparts, were lethargic and isolated, “suffocating in pessimism and dismal introspection.” Made up almost entirely of middle-class intellectuals, pacifists resisted engaging with workers, the poor, and the broader middle class. Pacifism needed, Roszak thought, to evolve into a more ambitious social movement that tied opposition to war to other social and economic issues.

But Roszak also criticized the traditional left’s concentration on material issues. Reflecting on his sojourn a year later, he lamented a politics unleavened by “post-materialist” concerns. In an article for the Nation, he wrote, “When political parties talk about anything worthwhile at all, it is the bread-and-butter issues, which is the stuff man does not live alone by.” Only anarchists, “Marxist humanists,” and the nascent London bohemia were talking about cultural, even spiritual matters: anomie, alienation, the lack of meaningful work and community, the attrition and impoverishment of personal experience in advanced capitalist societies.

Over the next four years, Roszak shuttled back and forth between London and Hayward, acting less as an anthropologist of the counterculture than as a careful participant-observer. Along with other disgruntled academics, Roszak helped form the “Antiuniversity of London” in 1967, one of the first in an archipelago of “free universities” that blossomed over the next five years. Rejecting traditional hierarchies and curricula, the “Antiuniversity” attracted students, drifters, and other seekers eager to learn, in Roszak’s words, about “Timothy Leary, anarchist politics, and Tantric sex.” They often possessed little more, he recalled, than “guitars, begging bowls, and a stash of magic mushrooms.”

While he conceded to readers of the Nation that hippies were “a scruffy, uncouth, and often half-mad lot,” he diagnosed their raffish alienation as “a symptom of grave default on the part of adults.” That dereliction was not, as Joan Didion wrote in her grim and apocalyptic “Slouching Toward Bethlehem” (1967), that “we had somehow neglected to tell these children the rules of the game we happened to be playing,” but rather that the game itself was so unjust and dishonest that the children were refusing to play. Middle-class adults had failed to articulate any worthy and demanding ideals. The Organization wanted only diligent workers and consumers, while the State wanted cannon fodder. Yet Roszak knew that even the left and its traditional constituencies—industrial workers and racial minorities—were usually hostile to the new counterculture. Thoroughly bourgeois in its mores, the Old Left was stuffy, prudish, and judgmental, while unionized workers and the non-white poor wanted not to reject but to savor and accumulate the fruits of technological innovation. Indeed, the counterculture vilified the very standard of living to which the Old Left had always aspired.

Thus, although Roszak recoiled from the drug scene and (apparently) refrained from sexual adventures (“he had his feet on the ground,” as Betsy later told an interviewer), he sensed that the counterculture harbored more than delinquency from middle-class mores. If, for rebellious youth, Marxism had become—like the Baltimore Catechism of Roszak’s youth—a set of “lifeless verbal formulas,” it was because it repressed a transcendental impulse that cried out for life. By the late 1960s, Roszak was convinced that the counterculture offered a more trenchant critique of the affluent society than most conventional forms of radicalism. “There was more to these matters than sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll,” as he mused in 2007. Eager to explain the new children’s crusade to the elders—and even to the children themselves—he embarked on a mission to give the counterculture “a more accessible philosophical translation.”

Roszak wasn’t the first to attempt a “philosophical translation” of the counterculture. When the Beat phenomenon began to coalesce in the San Francisco of the mid-1950s—especially in the literary culture created by Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Kenneth Rexroth—many writers flocked to the Pacific Coast to study the folkways of this aberrant tribe. In The Holy Barbarians (1959), the journalist Lawrence Lipton traced the genealogy of the Beats back through the leftists of the 1930s and the expatriates of the 1920s. The difference was that the young people Lipton encountered in Venice, California, were not “protesting” anything; in his telling, they were “disaffiliated” rather than alienated, uninterested in being a revolutionary vanguard. To the anarchist social critic Paul Goodman, “the Beat Generation” he described in Growing Up Absurd (1960) was a “major pilot study of the use of leisure in an economy of abundance.” Goodman wasn’t too impressed with the results: Beat literature and religious heterodoxy struck him as all too “ignorant and thin,” and he wished they weren’t so dependent on “ancient superstitions and modern drugs.”

At the same time, in the wake of the barbarism unleashed during World War II—the strategic bombing conducted by both the Axis and the Allies, the nuclear devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and, above all, the Holocaust—some on the left grew disappointed with the inherited political traditions of modernity. In Norman O. Brown’s words, many liberals and socialists witnessed in these events “the superannuation of the political categories which informed liberal thought and action in the 1930s.” The ominous sense that there was something fundamentally perverse about modern civilization—a position usually attributed to conservatives—pervaded postwar “personalism,” a constellation of religious and secular thinking that included Muste, Goodman, Dorothy Day, Dwight Macdonald, and contributors to journals such as politics and Liberation, two prominent venues for pacifists, anarchists, and other non-Marxist radicals. Personalists were appalled by the leviathan scale of contemporary social and economic structures and by the enlistment of science and technology in the service of mass extermination. They argued not only for more decentralized and face-to-face communities but for new forms of political ontology that could replace both left or right versions of realpolitik. As Muste insisted, “there are in our universe resources for living the life of love which we have hardly begun to tap, but which we must learn to draw upon.” In the personalist political imagination, love was a power and not merely an ideal.

The vernacular of “love” was not alien to the American left. In the Progressive era, Randolph Bourne had envisioned the goal of radical politics as “the good life of personality lived in the Beloved Community.” In the Port Huron Statement Hayden described “participatory democracy” not only as a form of governance but as a way of life devoted to exploring our “unfulfilled capacities for freedom, reason, and love.” Characterized by “fraternity and honesty,” a new, more substantial democracy would “replace power rooted in possession” with “power and uniqueness rooted in love, reflectiveness, reason, and creativity.” The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) echoed Bourne’s hope for “beloved community,” translating it into a more Christian idiom in its brief and forthright “Statement of Purpose” (1960). The SNCC sought a “social justice permeated by love,” and defined love as “the force by which God binds man to himself and man to man.” When Martin Luther King Jr. declared that “the moral arc of the universe is long, and it bends toward justice,” he did so confident that the arc was part of a larger cosmology in which love was the quintessence of the universe. As he put it, “Unconditional love will have the final word in reality.”

As a fellow-traveler of this personalist milieu, Roszak commenced his countercultural project with an anathema upon the multiversity: The Dissenting Academy (1968), in which he assembled a number of left-wing scholars—the historian Staughton Lynd, the sociologist Gordon Zahn, and the linguist Noam Chomsky, among others—to indict the intellectual and political subservience of professors to the national-security state. Rather than act as “handmaidens” for the corporation or the Pentagon, universities, Roszak demanded, must renounce their narrow conception of “service” and become “an independent source of knowledge, value, and criticism.” Though encouraged by the student uprisings at Berkeley in 1964 and Columbia in 1968, Roszak argued that the prominence of academics in the citadels of power meant that something about academic life itself had led to the intellectual legitimation of the war. By sanctioning both thermonuclear weapons and the brutal tactics of “counter-insurgency,” the Cold War professoriate had violated and even abandoned “any defensible standard of intellectual conscience.”

Roszak echoed a broader radical critique of higher learning in America, one that called into question the wisdom and benevolence of those Chomsky had dubbed “the new mandarins”—scholars who swanned between the multiversity and the Beltway political directorate, epitomized by McNamara, McGeorge Bundy, and the “Whiz Kids” in the Kennedy administration. As Chomsky had asked in American Power and the New Mandarins (1969), “What grounds are there for supposing that those whose claim to power rests on knowledge and technique will be more benign in their exercise of power than those whose claim is based on wealth or aristocratic origin?” Their meritocratic hauteur made them “dangerously arrogant, aggressive, and incapable of adjusting to failure”—a judgment confirmed by the butchery in Vietnam, produced and directed by the Whiz Kids. Radicalized by the antiwar movement, many young scholars embraced Chomsky’s skepticism, sponsoring teach-ins, sit-ins, demonstrations, and “free universities.”

The crescendo of university tumult came in the spring of 1969, when teach-ins and work stoppages at over thirty major universities provoked the social critic Paul Goodman to identify a “religious crisis” among younger intellectuals in New Reformation (1970), his keen diagnosis of the maladies besetting university life. The title was carefully chosen: the savagery of the Vietnam War, as well as the growing awareness of the ecological costs of industrial growth, provoked intellectual youth to blaspheme the liberal faith in science and technology—a “beneficent religion” whose promises were increasingly perceived as hollow or lethal. Though put off by the splenetic self-righteousness of many cultural and political radicals, Goodman nonetheless praised the “metaphysical vitality” of dissident students and the counterculture.

While Roszak stopped short of characterizing faith in science and technology as a religion, he did consider it a myth: not a lie or a legend, but rather a story that illustrates a culture’s most cherished values. In advanced industrial societies—both capitalist and socialist—the preeminent narrative was “the myth of objective consciousness,” a “Reality Principle” purportedly “cleansed of all subjective distortion, all personal involvement.” “Objective consciousness” was the purely instrumental rationality maligned by Frankfurt School Marxists, the “one-dimensional thought” of vapid efficiency and technological prowess excoriated by Marcuse. Affirming Weber’s account of “the disenchantment of the world,” Roszak traced the origin of objective consciousness to Protestantism’s aversion to Catholic sacramentality, then followed its growth through the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions. Objective consciousness claimed to be unbiased, disinterested, and antiseptic, hermetically sealed against the vagaries of passion, desire, or ideology. “Objective consciousness” also denied the terrestrial efficacy of any supernatural power, explaining the world entirely in terms of forces that could be identified and measured scientifically.

Objective consciousness was the cultural foundation of what Roszak called “the technocracy”: the conglomerate of executives, managers, scientists, technicians, and politicians who made up the ruling elites of industrial civilization. United by a faith in the legitimacy of scientific and technological expertise—“the prestigious mystagogy of the technocratic society”—the technocracy justified its authority by invoking the allegedly “objective” standards of economic growth and technological progress. Roszak never denied the material benefits of the technocratic regime; but the technocracy’s munificence was, in his view, at once its most convincing argument and its most treacherous seduction. Like critics such as Jacques Ellul, Lewis Mumford, and even Norbert Wiener (the penitent father of cybernetics), Roszak feared that industrial societies would allow prosperity to cover a multitude of sins. “Deeply endorsed by the populace,” the mystique of technocracy legitimized the exploitation of workers, a callously extractive relationship to nature, and—most perniciously—“the repression of the religious sensibilities,” the erasure of spiritual vision and hope from the minds of modern societies.

Roszak saw no alternative to technocracy on the standard liberal-left spectrum. In his view, Soviet socialism, European social democracy, and Great Society liberalism were all mere appendages of the soulless technocratic regime. Though he noted Marcuse’s status as an intellectual preceptor to the New Left, Roszak rejected the psychoanalytically inflected Marxism of Marcuse’s Eros and Civilization (1955) and An Essay on Liberation. For all his celebration of the freedom made possible by technologically generated abundance, Marcuse had to resign himself, in the end, to the melancholy necessity of death. This herald of liberation, Roszak shrewdly observed, “cannot conceive of life as anything other than a tragic discontent.”

Roszak was more sympathetic to Norman O. Brown, whose Life Against Death (1959) remains one of the boldest and most searching artifacts of psychoanalytic cultural criticism. Brown’s contention that we could overcome the fear of death, recover the sensual enchantment of the infant body, and dwell in the joyful exuberance of Eros was more radical, Roszak believed, than Marcuse’s revolutionary but mournful vision. Roszak applauded Brown for “going off the deep end” into religious territory: Brown’s more oracular later work—especially Love’s Body (1966)—offered a portal into what Roszak called “the visionary imagination,” an ontological dimension traversed by mystics, Romantic poets, and now the counterculture.

For Roszak, the counterculture was the unlikely but legitimate heir to this prophetic tradition. The counterculture’s exemplary prophet was Allen Ginsberg, the notorious author of “Howl” (1956) who launched the Beats into international prominence. In Ginsberg’s poetry, Roszak thought, “the cry is not for a revolution, but for an apocalypse: a descent of divine fire,” a flame that illuminates the world as a province of everyday epiphanies. Often set in subways, bathrooms, offices, and factories, Ginsberg’s poems exhibited “an unashamed wonder at the commonplace splendors of the world.” Ginsberg’s popularity suggested to Roszak that the counterculture represented “a new, eclectic religious revival.”

In Making of a Counter Culture and especially in Where the Wasteland Ends, Roszak probed this religious revival with a deft and sympathetic intelligence, suggesting an elective affinity between his own spiritual pilgrimage and that of the counterculture. Roszak assumed that orthodox Christianity had nothing to offer the counterculture: discredited by science and corrupted by its unctuous fealty to power, it would survive only as long as it posed no threat to the technocracy. The counterculture turned instead to what Roszak called “the Old Gnosis,” or—more revealingly—“sacramental consciousness”: “the old way of knowing, which delighted in finding the sacred in the profane,” and which encountered the “really real” through “a visionary style of knowledge, not a theological one.” “Its proper language is myth and ritual; its foundation is rapture, not faith and doctrine; and its experience of nature is one of living communion,” he wrote. Unlike the scientist, the technician, or the capitalist, the avatars of sacramental consciousness—the shaman, the magus, the oracle, the sibyl, the prophet, the poet, or the artist—not only hope but “know that there is more to be seen of reality than the waking eye sees.”

One could easily—perhaps too easily—characterize Roszak’s account of sacramental consciousness as a projection of his truncated Catholicism onto the counterculture. He discarded penance and the Baltimore Catechism while retaining the mysteries of the sanctuary. Roszak spoke for millions whose religious experience, such as it was, had been stiflingly doctrinal and moralistic, devoid of what William James once called “ontological wonder”: a gratitude for the sheer actuality of things that lies at the heart of all true reverence. Orthodox religion, in Roszak’s view, had countered the myth of objective consciousness by inadvertently imitating it, insisting on moral and doctrinal scrupulosity at the expense of jubilation and ecstasy. The sacramental consciousness survived outside church walls in the Romantic tradition—in Blake’s “auguries of innocence” and William Wordsworth’s “sense sublime.”

The pre-scientific sacramental imagination is what Roszak believed the counterculture sought in psychedelic drugs—a pharmaceutical beatitude that he dismissed as “a counterfeit infinity.” Too many young people believed that drugs would give them the same kind of aesthetic and spiritual experiences that shamans or Romantic poets enjoyed. But Native Americans ingested peyote in careful religious rituals, and William Blake needed no mescaline to witness the marriage of heaven and hell. Besides, Roszak noted, middle-class Americans already relied too heavily on drugs—to sleep, wake, work, have sex, evacuate, or relax. He lamented that when Timothy Leary advocated LSD as “better living through chemistry,” he meant it “the way Du Pont means it”: the message was that “there exists a technological solution to every human problem.” (Roszak identified Leary early on as a blend of the guru and the grifter.) Drug use was already fueling the rise of a hippie capitalism: not only the illegal drug trade, but “head shops” that sold psychedelic commodities like any other petty-bourgeois enterprise. Anticipating Thomas Frank’s critique of the “conquest of cool,” Roszak predicted that even the technocracy would eventually get its groove on: “It can let long hair grow in high places. It knows how to swing.” The Organization Man in the gray flannel suit would buoyantly yield to the huckster in denim. The drug culture, Roszak predicted, would “distract the young from all that is most valuable in their rebellion” and “destroy their most promising sensibilities.”

For Roszak, the counterculture’s greatest promise lay in a “visionary commonwealth,” a federation of spiritual renegades resisting the technocracy and plumbing “the religious dimensions of political life.” What bound these renegades together was their awareness that “politics is metaphysically and psychologically grounded.” If the world is composed of nothing but forces to be mastered by science and technology, then politics is just the administration of people and things in accordance with the latest expertise. But if the world contains forces that elude the control of the professional intelligentsia, then a different sort of polity is possible, one whose deliberations can be informed, not only by expertise, but by “magic and dreams,” archaic lore, and “visionary poetry.” In the nuclear age, the stakes were nothing less than the survival of the species. Once, Roszak reflected, the spiritual renegades could withdraw from the moral and spiritual pestilence around them: “the God-intoxicated few could abscond to the wild frontiers, the forests, the desert places to keep alive the perennial wisdom that they harbored.” But there were no such refuges left. If the party of “sacramental consciousness” wanted to resist the technocracy, “they must now become a political force.” If not, “their tradition perishes.”

The future political economy of this visionary commonwealth would not be anarchy, in the pejorative sense of chaos, but anarchism—“the political style most hospitable to the visionary quest.” Preceded by the early Christians, Taoists, Buddhists, medieval heretics, radical Protestants, Romantics, and the utopian communities of antebellum America, anarchism represented the desire for personal fulfillment in a beloved community. “A wisdom gathered from historical experience,” anarchism was not an arcane ideological system such as Marxism; it favored mutual aid, freedom from bosses and bureaucrats, and direct workers’ control of production. Long dismissed as the bray of peasants and artisans crushed by industrialization, anarchism, Roszak thought, was reappearing in “the communitarian experiments and honest craftsmanship of the counterculture”: organic farms, cooperatives, and rural and urban communes. Roszak argued that “peace and personal intimacy” required “the life of small, congenial groups.”

It was no surprise, then, that Roszak wrote the introduction to the U.S. edition of E. F. Schumacher’s Small Is Beautiful (1973). With his numerous references to Buddhism, Hinduism, and scholastic philosophy (Schumacher had converted to Catholicism a few years before), the British economist and philosopher impressed Roszak as “the Keynes of postindustrial society.” Following Schumacher’s counsel that “the task of our generation is metaphysical reconstruction,” Roszak rejected not only capitalism and its “phony plebiscite of the marketplace,” but also the dubiously “objective” assumptions of the discipline of economics: inert, disenchanted matter, a metaphysical “scarcity” that licensed competition, and a conception of men and women as nothing more than rational utility-maximizers.

Writing at the dawn of the neoliberal era, Roszak was faintly hopeful that countercultural economics could prevail. “If there is to be a humanly tolerable world on this dark side of the emergent technocratic world-system,” he claimed, it would emerge from the “fragile renaissance of organic husbandry, communal households, and do-it-yourself technics.” Over the next generation, however, the technocracy triumphed, evolving into a ruthless plutocracy. Invaluable and indispensable as they are, “small, congenial groups” were not enough to withstand the juggernaut of capital accumulation. Yet the more fundamental problem with Roszak’s “philosophical translation” of the counterculture was that it was never clear how seriously Roszak took any particular manifestation of “sacramental consciousness.” Animism, karma, and Christian sacramentality are extremely different forms of what Roszak called “visionary splendor.” If politics is indeed metaphysically grounded, we need more than an amorphous sense of “transcendence” to foster solidarity.

Roszak believed the Christian tradition was so compromised by its subservience to power that only the broadest syncretism could preserve the sacramental imagination. But is Christianity really as exhausted as Roszak believed? Two of his contemporaries, Thomas Merton and Kenneth Rexroth, drew upon “sacramental consciousness” for some of the period’s most incisive social criticism, echoing the counterculture’s impatience with “objective” rationality. “Every blade of grass is an angel in a shower of glory,” Merton rhapsodized in 1966, “every plant that stands in the light of the sun is a saint and an anthem.” An erudite and still undercelebrated poet and critic, Rexroth urged his fellow radicals to be saintly, as “the saint saw the world as streaming / In the electrolysis of love.” Though modified by elements of Buddhism and Taoism, Rexroth’s religious anarchism flowed naturally from this sacramental perspective. For him, anarchism was a form of “agape, the love of comrades in a spiritual adventure.”

The left—even much of the Christian left—has grown shy and embarrassed about the language of love in political life, convinced that the only realistic dialect is that of power, interest, victory, and defeat. (Cue the snarky references to Marianne Williamson.) But if we really believe that the power of love resides in the marrow of creation, then that assurance must inform our political imagination. Roszak’s countercultural wisdom receives an imprimatur of sorts from Pope Francis in Laudato si’ (2015), his encyclical on ecology and economics. Opposing the same “technological paradigm” that Roszak and the counterculture rejected, Francis claims that love is “the fundamental moving force in all created things,” and that our efforts to dispel the false objectivity of our technocratic age must be “illuminated by the love which calls us together into universal communion.” It is not enough to speak truth to power as long as truth is understood in exclusively scientific terms; we must also speak love to power. Roszak reminds us that, despite all its confusions and excesses, the counterculture of the 1960s conveyed the oldest and most venerable realism.