Twice in my life I’ve put my head in my hands and cried after learning that a singer-songwriter I loved had died. The first time was when Johnny Cash went to his reward and rejoined his beloved June. The second time was yesterday, when I read the news that Billy Joe Shaver had passed away at eighty-one years old.

I saw Billy Joe play only once, now well over a decade ago, at a small theater in Virginia. There was no opening act. Instead, his set was preceded by a screening of the documentary The Portrait of Billy Joe, which had just been released—an intimate, gut-wrenching look at the truest of all the Texas troubadours. The teaser for a profile of him published in Texas Monthly in 2003, not long before the documentary came out, gives a sense of the life that provided such abundant material for the filmmakers:

In his 64 years, the Corsicana native has been a cotton picker and a roughneck, a screwup and a scoundrel. He’s hit the bottle, hit rock bottom, and been born again. He married the same woman three times, mounted multiple comebacks, survived a heart attack onstage and the deaths of nearly everyone he’s ever loved. All of which explains why he’s one of the greatest songwriters in the world.

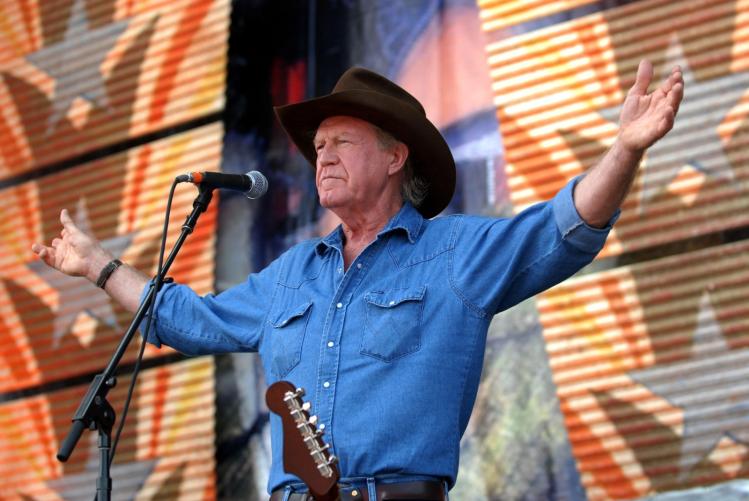

One of the details missing from this description is that, when he was a younger man, Billy Joe lost two fingers on his right hand during a stint working at a lumber mill. The accident meant that, while he sometimes strummed along as he sang, more often he set aside his guitar and performed his songs—flapping his arms, punching a fist into the air, using his entire body to convey the emotion behind them. The night I saw him, he made his way down from the stage after the show, wading into what remained of the crowd. And there he was, right in front of me. The only reaction I could muster was to stick out my hand and tell him that he was great. That instant, however, I knew I’d ventured into awkward territory—the hand I went to shake was the one with the missing fingers. He saw the look on my face, but didn’t flinch, grasping my hand and replying, “Thank you, that means so much.”

Many singers tell tales of drunks and addicts, cheaters and brawlers—many are those things. But their names will be forgotten while Billy Joe Shaver’s endures. What set him apart is that he never flinched, as an artist or as a man. He offered his wounds to listeners, just as he offered me his hand.

Those wounds were many. Billy Joe once wrote, “My grandma’s old-age pension is the reason that I’m standing here today”—and that was the truth. He was the kind of songwriter who had the term “hardscrabble” constantly appended to his upbringing. But his deepest wounds were bound up with his many shortcomings as a husband and father. The pain in so many of his songs is that of a man who has wronged his woman and his children, and knew it. In “Blood is Thicker Than Water,” a duet with his son, Eddie, on the last album they made together, The Earth Rolls On, the younger Shaver sings:

I’ve seen you pukin’ up your guts and runnin’ with sluts

When you were married to my mother

Now the powers that be are leadin’ you and me like two lambs to the slaughter

I need a friend, I’m your son and you’re always gonna be my father

On Victory, an earlier album from “Shaver”—the name father and son gave their band—Billy Joe had recorded these words in “Live Forever”:

You fathers and you mothers

Be good to one another

Please try to raise your children right

Don’t let the darkness take ’em

Don’t make ’em feel forsaken

Just lead ’em safely to the light

That song would become especially wrenching to listen to when Eddie died of an overdose shortly after he and Billy Joe finished recording The Earth Rolls On. Eddie’s friend Todd Snider memorialized him in “Waco Moon,” a lament that the supremely talented guitar player had wasted his gifts (“Quit too late, died too soon”). But what comes through most of all is Snider’s pain over Eddie abandoning his father—that pain mingles with anger when he describes “the selfish way you left your dad / When you know what a hard luck time he’s had.”

Snider’s response to Billy Joe’s vulnerability is the same as the listener’s. In unadorned yet poetic language, Billy Joe unfurled his sorrows and regret. His lyrics remind us that our failures finally lead back to the human heart in conflict with itself. Out of that conflict he fashioned profound songs about sin and a longing for redemption, songs in which our everyday lives point toward eternity.

Those memorializing Billy Joe will surely note that he wrote nearly every song on Waylon Jennings’s breakthrough outlaw album, Honky Tonk Heroes, and rightly so. His catalogue is unparalleled, and his achievements deserve our recognition. But what I keep coming back to is the night that I met him. The documentary that was screened before Billy Joe played included footage of him giving his testimony to a little Bible church in Texas. He recalled being strung out and wandering into a cave overlooking a cliff. He thought of killing himself. In his confusion and grief, Jesus came to him in a vision. Until his last song, he labored to convey that vision. He knew that we live forever—and that our work here and now is to be the light that casts out the darkness, until that day when the light is all there is.