In times of crisis I return to books first read years ago and set in eras gone by—not to take refuge in the past, but to gain perspective on the troubled present (so often the reason we look to earlier texts, after all). Our present and its troubles persist, not that I would have imagined this nine or ten months ago when COVID-19 arrived in New York. But with the president and his allies soon to politicize the pandemic and then flatly deny its ever-worsening toll, I wanted something that might shed light on our moment, noisy with nationalism and the kind of paranoid conspiracy-mongering Richard Hofstadter first cataloged decades ago. It was still there on my shelf: Robert Stone’s 1966 debut novel, A Hall of Mirrors (Mariner Books, 416 pp., $19.95).

The timing was right for more reasons than one, given that the spring also brought a new Stone biography and a collection of his essays (both courtesy of Madison Smartt Bell, and both also recommended). These informed my reappraisal of A Hall of Mirrors, which I’d last read about twenty-five years ago. Back then, though impressed by Stone’s method, I was put off by his register—druggy, mystic-hipster pronouncements on the American psyche, a little high on its own supply. But a quarter-century made a difference. Stone’s tale of lost souls stumbling into a New Orleans subculture of fundamentalist Christians, bigoted conservative schemers, and corrupt local politicians is far more complex and original than I remembered, and now also reads as prescient.

As would become his regular technique, Stone moves us among multiple protagonists, though here the two who count most are Reinhardt and Geraldine. The former is a hyper-literary, fast-talking drifter; the latter, a tragically unlucky-in-love waitress bearing the literal scars of bad relationships. Both, it may not surprise, are drunks, and though booze may bind them there is also something like love at work. It’s when Reinhardt lands a gig as a conservative radio talk-show host that A Hall of Mirrors reaches out of the past to touch us now: he has no interest in ideology but knows just what to feed a rabid audience. If Stone isn’t entirely successful in resolving his sprawling plot—it is his first novel, remember—well, that may not be the point.

“I think growing up Catholic, taking it seriously, compels you to live on a great many levels,” Stone wrote in his 1987 essay, “The Way the World Is.” Living on many levels is also necessary to the novelist’s empathic obligations. At one point, the drunken Reinhardt and Geraldine read from a battered poetry anthology, eventually stopping to mull over the tenth stanza of Part IV of “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” and the notes Coleridge provided alongside: “[T]hey enter unannounced, as lords that are certainly expected and yet there is a silent joy in their arrival.” The beauty of the language moves them but also prompts an unlikely admission from Reinhardt. “Sometime I would like to arrive somewhere and have my arrival provoke silent joy,” he says. “I don’t think I have ever arrived anywhere and provoked that.” It isn’t self-pity. It’s expressive of a basic human desire that, when unfulfilled, can manifest in the despair and anger that Stone was attuned to when he wrote A Hall of Mirrors. And it serves in understanding Reinhardt’s dark epiphany later on: “I believe there’s a kind of man among us who feeds on pain to keep himself alive.”

The image of living on many levels came back to me in reading Carolyn Forché’s remarkable 2019 memoir, What You Have Heard Is True (Penguin Books, 400 pp., $18), a firsthand account of the unfolding horrors in El Salvador between 1978 and 1980. (See our April 2019 interview with Forché, “I Just Had to Say Yes.”) There’s an implausible, almost fantastical quality to its beginnings: the young poet is visited in California by a friend’s mysterious relative, a loquacious stranger who has driven from El Salvador in hopes of bringing her back with him to chronicle the conditions that will soon plunge the country into conflict. He is Leonel Gómez Vides, and almost against her wishes Forché accepts his invitation.

In the course of multiple and increasingly lengthy visits, Leonel immerses her not only in the anxious day-to-day life of a country on the verge of war, but also in the dark and tangled history that has brought El Salvador to this point. Forché accompanies Leonel on increasingly dangerous travels through the countryside and mountains, visiting impoverished workers, getting stopped at military roadblocks, happening on the remains of ordinary people slaughtered by the government. On her stays in the capital, she is introduced to politicians, businesspeople, and American diplomats—all of whom seem to have some unknown but apparently significant stake in how things might play out. She witnesses death squads snatch people off the street in broad daylight. She herself is soon under surveillance, suspected of being anything from a CIA agent to a co-revolutionary.

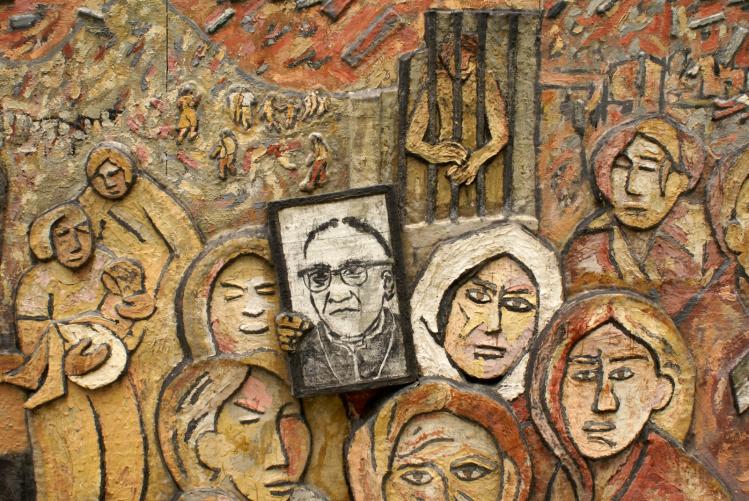

Her safety seems even less assured after visits with Archbishop Óscar Romero (whom she describes as emanating “an emulsion of light, such as sanctity bestows”). Romero urges her to return to America, exhorting her to report on what she has witnessed—the sufferings of the poor, the repression, the injustice—assuring her, against her own doubts, that “the time would come for me to speak.” Forché ultimately spent fifteen years at work on her account. “Every evil permitted anywhere in the world could spread to the whole of the world,” she comes to understand. This realization, of course, is also a warning. Decades after the events Forché describes and more than a year since its publication, What You Have Heard Is True demands urgent reading.

I have no excuse for not having read anything by Louise Erdrich until this year, and after finishing Future Home of the Living God (Harper Perennial, 288 pp., $16.99) I am eager to make up for lost time. I found a copy of her 2017 novel in a box left out on a Brooklyn stoop (the streets of my neighborhood are fertile ground for literary foraging) and, having recently enjoyed Anthony Domestico’s interview with Erdrich in Commonweal (September 2020), quickly set to work.

I was surprised and delighted to discover within the opening pages that the first-person protagonist is the editor of “a magazine of Catholic inquiry.” But that’s not even the most appealing or important of her qualities. Twenty-six-year-old Cedar is the adopted daughter of a liberal Minneapolis couple, Ojibwe by birth, and four months pregnant at the novel’s outset—vital to Erdrich’s speculative premise: worldwide biological evolution has somehow come to a halt, and indeed seems to be moving backward. As the crisis grows, pregnancy and childbirth become matters of state security, and laws targeting pregnant women for capture are enacted.

Why immerse oneself in a dystopia in this most dystopian of years? Because Erdrich doesn’t confine herself to the genre’s conventions. The novel also succeeds as a thriller, a work of spirituality, a commentary on women’s agency, and, ultimately, literature. Then there’s Cedar herself, a winning and indefatigable narrator addressing herself to her unborn child. She has long believed that “there is nothing that one human being will not do to another,” but late in the book reflects on a passage from Merton: “With those for whom there is no room, Christ is present in this world. He is mysteriously present in those for whom there seems to be nothing but the world at its worst.” In this she allows herself, as well as the reader, to find comfort and hope.