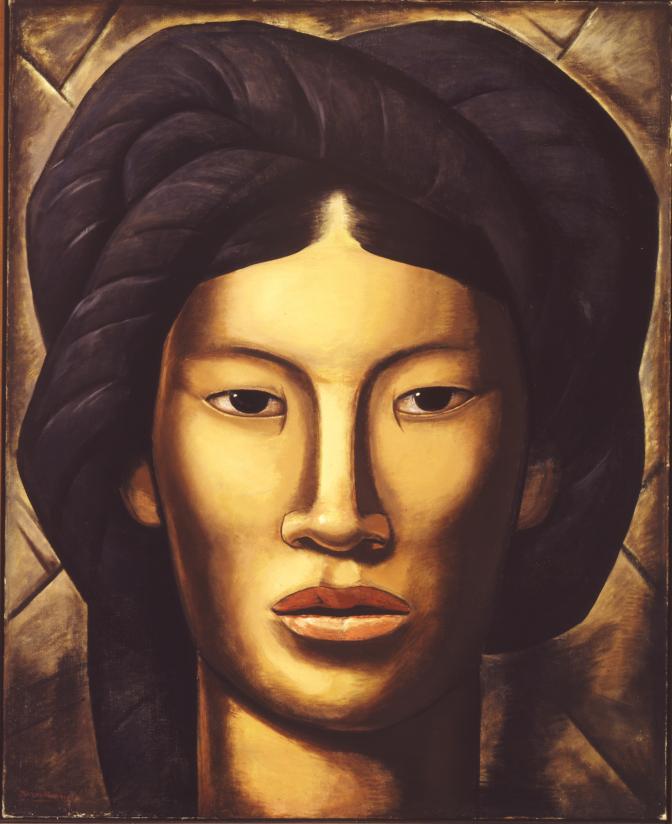

La Malinche, or Malintzin in her native Nahuatl, is one of the most fraught figures in Mexican history. How you see her depends on how you look. Sold into slavery as a girl and then given by the Mayans to the Spanish conquistadors in 1519, Malintzin served as an interpreter and advisor to Hernán Cortés, helping him defeat the Aztec empire. She also gave birth to his son, one of the first mestizos. Her legacy is thus contested: some view her as the mother of all Mexicans, others as a traitor to indigenous people. That’s largely what makes Alfredo Ramos Martínez’s 1940 portrait La Malinche so powerful: instead of a symbol, he portrays her as a person. Using a heavy, almost sculptural palette of browns and blacks, the artist depicts this “young girl from Yalala, Oaxaca” in extreme close-up, framed only by her thin neck and thickly wrapped braids. Her wide-eyed, stoic expression is at once a defiant defense, and a cautious invitation to intimacy.

La Malinche also happens to have brown skin, a trait she shares with many subjects in the nearly two hundred works included in Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925-1945, on display through January 2021 at the Whitney Museum in New York. Audiences and critics have rightly hailed the show, which arrives just as American cultural institutions (and the Whitney in particular) are facing growing calls to diversify their offerings. But there’s more here than a mere historical corrective to the dominant understanding of modernism, which has long favored the abstract over the figural, and white male artists over female artists and artists of color. With its massive gallery space organized around two distinct poles—Mexico at one end and the United States at the other—Vida Americana immerses visitors in a creative “borderland.” Instead of a wall, curator Barbara Haskell presents a crucible, in which Mexican and American artists of different ages, genders, ethnicities, and ideological convictions collaborated, experimented, and learned from each other as they forged something new.

Americans were enthusiastically drawn to Mexican culture in the early 1920s, when the new post-revolutionary Mexican government, led by leftist President Álvaro Obregón, funded a robust program of public art to celebrate (and propagate) the populist ideals of the revolution. The primary cause of the civil war, fought over ten years, had centered on agrarian reform, with the revolutionaries intent on freeing impoverished campesinos from exploitation by the country’s wealthy landowners. In response, painters like Ramos Martínez produced epic scenes of round-hatted, bullet-belted zapatistas, farmers-turned-guerilla-fighters led by the southern revolutionary general Emiliano Zapata. Artists also turned to the women and children left behind in the fields and rural villages, depicting them, often with dazzling greens, yellows, and pinks, in the act of harvesting crops, selling flowers, and dancing at festivals. Indigenous culture swiftly came to form the new core of Mexican identity: even Frida Kahlo, in two striking self-portraits (Me and My Parrots and Self-Portrait with a Monkey), accentuates her peasant clothes, brown skin, and dark hair—braided over her head, of course, in the traditional style of La Malinche.

Known in Mexico as “romantic nationalism,” this pictorial trend, featured in new periodicals like Mexican Folkways, inspired many American artists—painter Henrietta Shore and photographer Paul Strand among them—to travel the Mexican countryside in search of “authentic” subjects. Shore’s Women of Oaxaca (1927) displays a line of curvy figures processing along a range of rolling mountains as they carry jet-black water jugs on their heads, while Strand’s Woman and Boy, Tenancingo, Mexico (1933) shows the pair, wrapped in patterned garments, posing against a door frame. In both instances, these depersonalized subjects become mere stand-ins for an idealized, pre-modern purity—an attitude encouraged by Mexico’s Tourist Department in kitschy travel-ad films like Tehuantepec, Mexico (1943), which gushes over the “free and regal carriage” of that village’s “amazing and lovely creatures.” These indigenous women, the narrator brags, are “taller than your average Mexican,” and so used to bearing heavy loads on their heads that it has actually improved their posture.

Not everyone was on board with such mythmaking. José Clemente Orozco, the least ideological and the most spiritually expansive of los tres grandes, the trio of Mexican muralists (Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros are the other two) who began exhibiting work and securing commissions throughout the United States in the late ’20s and early ’30s (after the Mexican government cut off their funding), was decidedly ambivalent about the revolution. His brooding 1931 painting Zapatistas is a case in point. In the foreground, Orozco gives us a few familiar tropes of romantic nationalism: seven men, almost disappearing beneath their round hats and long rifles, trudge through mountainous terrain as four weary, shawl-clad women follow them. Behind and above sit four larger-than-life generals, mounted on horseback and gazing down on the procession with a mixture of pity, indifference, and scorn. Orozco has drained the color palette, making it appear as if everything—the tall reddish-brown peaks, but also the generals’ horses, shirts, and faces—is smeared with dried blood. It’s hardly the most reassuring portrait of revolutionary solidarity.

Such iconoclasm made Orozco a natural draw for like-minded Americans, eager to absorb new forms capable of expressing their own complex relationships with a rapidly changing modernity. Chief among them was the young Jackson Pollock, who in 1930 made a pilgrimage to Pomona College in California to see Orozco’s mural depicting the Greek myth of Prometheus. (The original is installed in the college dining hall; curators have mounted a stunning replica in one of the galleries.) With a gaunt face modeled on Byzantine icons of Christ and a heaving torso fashioned after the ancient Greek Belvedere marble (housed in the Vatican Museums), Orozco’s Prometheus stands in diametrical opposition to Michelangelo’s sixteenth-century Creation of Adam, also in Rome (frescoed on the roof of the Sistine Chapel). There, a placid Adam reclines passively, ready to receive the spark of life from God’s mighty finger. But here, Prometheus, straining against his cramped, vaulted frame, rises from his knees to seize the divine flame by force. Small wonder that Pollock called it “the greatest painting done in modern times.” Pollock’s energetic, abstract adaptations of the figures and lines pioneered by Orozco—most notably The Flame (1934–38)—are displayed opposite the Prometheus replica. Their kinetic brush strokes, which prefigure Pollock’s later “action painting,” don’t just vibrate with the excitement of discovery; their brilliant reds, whites, and yellows burn with the warmth of gratitude.

If Mexican muralists taught their American admirers how to innovate formally, they also showed them a new way of thinking about what art could be, and who art was for. Midway through the show, the gargantuan works of Diego Rivera begin to dominate the galleries. Two of his most famous public murals are here. A video installation projects Detroit Industry (1932–33), whose twenty-seven hyper-detailed panels fill an entire courtyard at the Detroit Institute of Arts, while a full-scale wall replica displays Man, Controller of the Universe (1934), originally commissioned for 30 Rockefeller Plaza in New York but later moved to the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, after Rivera controversially insisted on including images of Karl Marx and Vladmir Lenin. Both murals reveal Rivera’s fascination with the spectacle of human labor amplified by modern technology: pistons multiply the strength of biceps as microscopes magnify the powers of the eye. The working masses, Rivera believed, had raised humanity to new heights. Artists needed not only to glorify such an ideology, but to demonstrate among themselves—through their collaborative, communal mode of working—the viability of the new fraternal world they believed was coming into being.

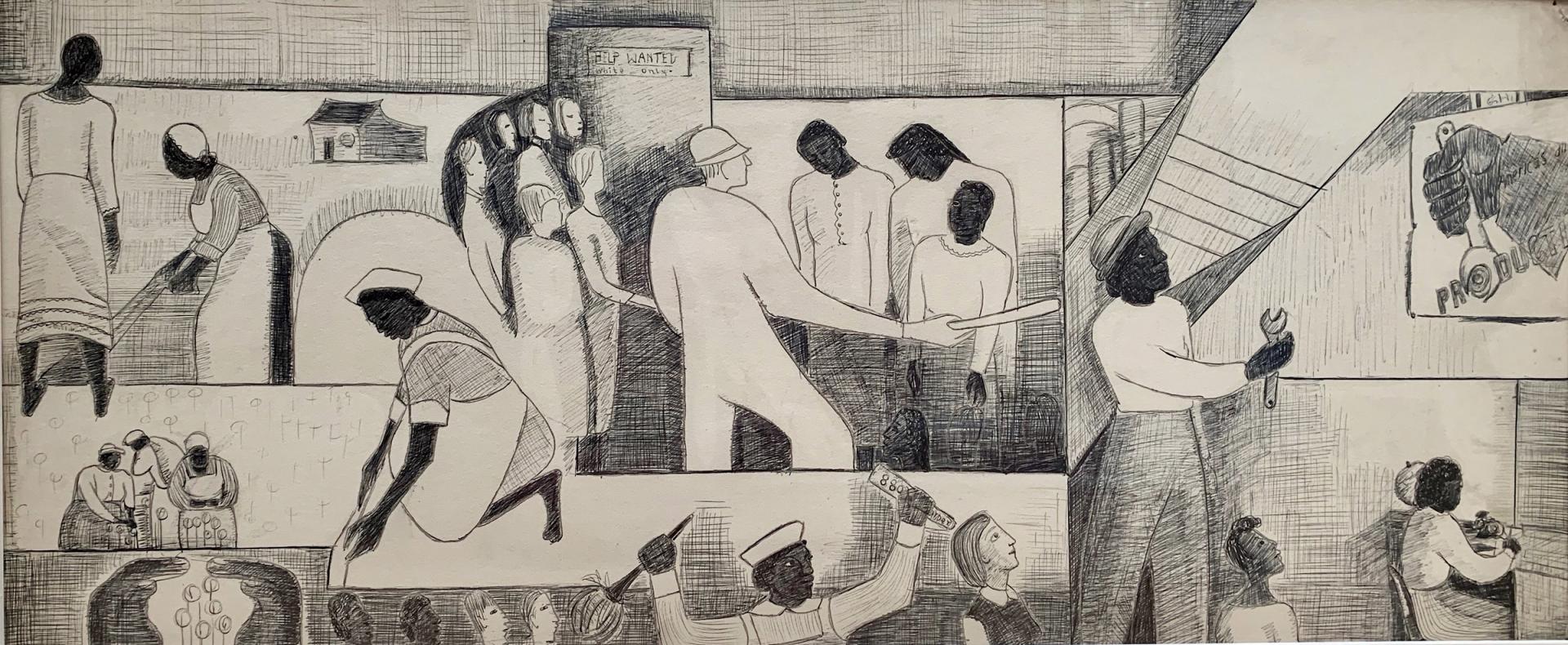

To that end, Rivera employed numerous American artists as assistants and apprentices on his projects, many of whom went on to become celebrated muralists in their own right. For the most part, Vida Americana focuses on large-scale historical cycles and smaller Works Progress Administration–funded paintings by well-known artists, such as Thomas Hart Benton and William Gropper. Rivera’s influence is clear, but the effect of so many muscular men pouring molten steel and pulling levers can be numbing. More interesting, and far more affecting, is a small black-and-white drawing on paper by Thelma Johnson Streat. The first African-American woman to have a work purchased by the Museum of Modern Art, Streat had assisted Rivera on an earlier project in San Francisco, earning his praise as “extremely evolved” and “one of the most interesting” artists in the United States. Her sketch for an unrealized mural, The Negro in Professional Life—Mural Study Featuring Women in the Workplace (1944), acknowledges the reality of racism but refuses to be paralyzed by it.

At the center of Streat’s composition we find an imposing white woman, standing with her back to us beneath a sign reading “Help Wanted. White Only.” Gripping a baton, she dismisses three Black job applicants, who in turn bow their heads in shame. Spiraling around this scene, though, are dynamic images of Black women working. One holds a copy of FDR’s Executive Order 8802, which prohibited discrimination in the defense industry. A second grasps a wrench as she gazes at a wartime production poster. Streat’s calmly defiant message is as simple as it is true: Black women deserve equal opportunities, and equal treatment under the law.

As the rest of the show makes clear (and as the events of summer 2020 visibly reminded us), reactionary political forces frequently attempt to squelch such assertions with violence. (Streat was threatened by the Ku Klux Klan in 1943, after her Death of a Black Sailor mural premiered in Hollywood.) To the raucous sound of a Mexican labor organizer bellowing in the background (a clip from the 1936 film Redes plays on repeat), the show’s last few galleries display dozens of drawings, paintings, and prints documenting the social unrest that convulsed America in the 1930s. In Philip Evergood’s American Tragedy (1937), a packed protest results in beatings, arrests, and a shooting at the hands of the police. Others are more gruesome, like a series of lynchings of African-American men, depicted in woodcuts by Elizabeth Catlett and Hale Woodruff. Only a few—like Joe Jones’s We Demand (1934), in which demonstrators march under elevated train tracks—are hopeful. Most are not.

It’s perhaps appropriate that a show that debuted in February 2020 should end on such a dark note. True, some Mexican artists, such as Siqueiros—the most formally innovative and temperamentally pessimistic of los tres grandes—continued working and experimenting with well-known Americans (like Pollock) through the end of World War II. But by the mid 1940s, the twenty-year period of Mexican-American collaboration had ended, and the spirit of enthusiastic artistic exchange had cooled. Today it can be hard to believe that such an era even existed in the first place. Vida Americana doesn’t tempt us to idealize it, but it does inspire hope for a renewed national willingness to celebrate and even learn from Mexico.