Fifty years ago, Quebec was in the throes of a secessionist movement, its French-speaking majority venting long-accumulated resentment at the dominant Anglo minority. In Canada, “the October crisis” signifies not the 1962 global confrontation over Soviet missiles in Cuba, but the domestic strife triggered in the fall of 1970 by the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ), which committed a pair of high-profile political kidnappings. Envied today for its political serenity, Canada back then seethed with anger stirred up by the FLQ, whose eloquent, impassioned leader was Paul Rose. Rose’s life and times form the subject of Félix Rose’s documentary film Les Rose, or “The Rose Family.”

While most children at some point discover something about their parents in a happenstance way, few can match what Rose heard from a cousin: “Your dad kidnapped a cabinet minister and killed him.” The idea for his film began with this shocking revelation. Who is a freedom fighter and who is a terrorist—and who gets to decide? How do we judge political violence committed in pursuit of justice? Rose addresses these abstract questions implicitly while pursuing concrete, personal ones: Who was his father, and how did he do what he did? “My dad wouldn’t hurt a fly,” Rose recalls thinking upon learning of his father’s revolutionary past. But a political hostage? Perhaps.

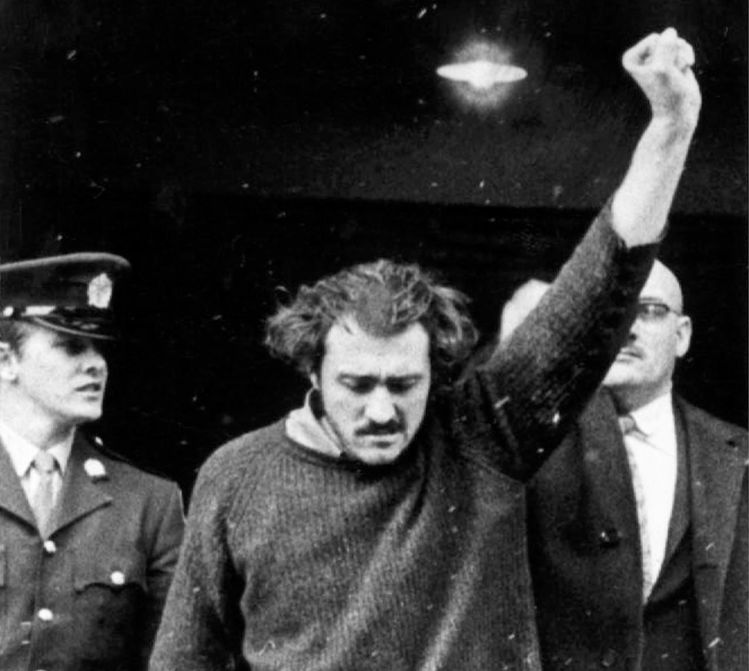

Rose père died in 2013, and the film opens at his memorial service, with family and friends paying tribute as a voiced-over news pundit comments discordantly on “the felon, the terrorist, Paul Rose.” The film deftly contrasts the private person with the political one: the older man we see in his living-room easy chair, bantering fondly with his son, versus the young man being led out of a courtroom, head bowed and fist raised in a classic pose of revolutionary defiance.

Les Rose is cobbled together from home movies, news footage, tape recordings smuggled out of prison during Paul Rose’s incarceration, and interviews his son conducts with family members, especially his uncle, Jacques Rose, a former FLQ member. We get an account of a hardscrabble Montreal childhood, both brothers working as teens at the Redpath sugar refinery where their father and grandfather had worked before them—for “starvation wages,” Jacques recalls, paid by “English bosses [who] got rich at our parents’ expense.” A deep class animus lay behind the separatist movement, a bitter sense of exploitation and marginalization that was more than working-class solidarity. French Canadians felt colonized within their own country.

After a stint as a teacher, Paul drifted toward political activism. His cultural coming-of-age is conveyed in emblematic 1960s scenes: worker committees; protestors taking down the Canadian flag and raising the Quebecois one; a visit by Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau that triggered a riot. We see footage of a summer in la Gaspésie, the rugged peninsula north of Quebec City, where in 1968 young people flocked for a hippie-ish mass gathering, playing guitars, smoking cigarettes, and befriending fishermen.

A mere two years later, these youthful larks led to a darker place. The FLQ had committed its first bombings in 1963—first mailboxes, then larger targets, culminating in a 1969 blast that heavily damaged the Montreal Stock Exchange. The mounting violence followed a script that was also playing out across Europe and the United States, in which resistance groups proceeded ineluctably from theory to protest to action: demonstrations, followed by bombs and robberies; and finally hostage-takings, ultimatums, and political executions. Insurrectionist provocations and government crackdowns ricocheted in a harsh tit-for-tat. “We had to up the ante,” Jacques recalls.

In October 1970, a faction of the FLQ kidnapped British diplomat James Cross. Paul’s faction then kidnaped Pierre Laporte, the deputy premier of Quebec. Publishing a manifesto “in the name of the workers” and pledging to “replace the slave society with a free one,” the group issued demands. The federal government refused to negotiate, and sent in the army. With troops closing in, the FLQ killed Laporte and left his body in the trunk of a car on a military base.

The Rose brothers were captured in December 1970 and herded through a trial whose legitimacy they rejected. Sentenced to life, Paul became a prison leader, chairing inmate committees and organizing cultural and educational events. After several contentious parole hearings and the defeat of a referendum on Quebecois sovereignty, he was released in December 1982, and spent the rest of his life building a family and working as a trade-union organizer and political activist.

Félix Rose has called his film an attempt to understand what impelled his father to political violence. Some critics have blasted the result. “Every son wants to see their father as a hero, but ‘Les Rose’ is a whitewashing of history,” wrote Marc Cassivi in the Canadian newspaper La Presse. One understands the criticism. Rose fuzzes out the full damage wrought by the FLQ (scores of bombings and at least nine deaths); we don’t learn the details of how Laporte was killed (he was strangled); nor does the film implicate Paul Rose in the actual killing, despite substantial evidence that he was involved. Absent too are interviews with government figures or historians; Félix Rose relies on family members, introduced with homey subtitles (“My Mother,” “My Aunt,” and so on), plus a few sympathetic friends.

Yet he nowhere denies the complicity of his father and uncle. Nor does he avoid hard questions; his film puts plenty of moral evasiveness on display. He draws amply from prison interviews with his father done in 1979 and 1980. Asked by a journalist what he had hoped to accomplish by kidnapping Laporte, a bearded and unrepentant Paul cites “consciousness raising” about “infringements of democratic practices.” And Jacques, pushed by his nephew, describes their actions as “the final solution when democracy failed.”

Such comments show that Orwellianism is by no means the sole property of governments in power. “We were requisitioning funds for the organization,” Jacques says of the robberies his group committed. “We called them mandatory donations.” He is not being ironic. Nor is his reference to “the people’s prison”—a converted dumpster the FLQ used for holding hostages. As for the fate of those held there, Paul recalls hesitating to put forth “ultimatums that could prove dangerous to the hostages,” as if the danger lay not in the decisions of the FLQ members, but in the negotiating process itself. “We never wanted a man to die,” says Jacques, looking back. “But it happened. We had no choice.”

Paul remained unapologetic about political violence, advocating it as a form of propaganda of the deed: political action intended not only to accomplish specific goals, but also to catalyze revolution. The concept was formulated by the German-American socialist-anarchist Hans Most (an influence on Emma Goldman), who advocated “action as propaganda” and whose 1885 manual, The Science of Revolutionary Warfare, was a primer for would-be bombmakers. The concept was a staple of such revolutionaries as Mikhail Bakunin, whose 1870 “Letters to a Frenchman on the Present Crisis” stated that “we must spread our principles, not with words but with deeds, for this is the most popular, potent, and irresistible form of propaganda.”

Tout comprendre, c’est tout pardonner, goes a French saying: to understand everything is to forgive everything. But while Les Rose understands, it stops short of pardoning Paul for continuing to espouse political violence, including the taking of human life. “I regret nothing,” Paul said in an interview with Le Devoir in the 1990s. “Placed before the same circumstances today, I would do exactly the same thing. It was not a youthful indiscretion.” Not a youthful indiscretion, but a conscious political plan. Yet it did not work. A wave of revulsion followed the Laporte murder and triggered, if anything, a loss of support for sovereignty.

Les Rose covers little of the last thirty years of Paul’s life, beyond brief clips of a middle-aged father doting on his kids. The uneventfulness of these years seems significant, and I would have liked more attention paid. What did it signify to Paul Rose to understand that life goes on, and that a type of change that is gradual, rather than cataclysmic—a change that reflects slow work, patience, and personal relationships—is the rule? The interviews of Jacques Rose take place at his house overlooking the St. Lawrence River, where he chats with his nephew while doing home renovations: the aging, ponytailed ex-terrorist, now the very image of the bourgeois retiree. “We just wanted people to get along,” he says. “That’s the ultimate goal of independence.” It seems a far cry from his long-ago fiery pledge to defeat the slave society through redemptive political violence. Uncle Jacques flies the Quebecois flag, and the roof of his home is a bold Quebecois blue: patriotism as home décor. At film’s close he is installing new, oversized windows throughout, as if to see more clearly.

An unsettling hybrid of family movie, political chronicle, and what might be called perpetrator history, Les Rose proves suggestive about the fraught nature of the ’60s and ’70s, and the limitations of the era’s revolutionary fervor. Arguably, part of the problem was grandiosity, the belief that political movements could, and should, solve all problems of existence with one fell stroke. “We wanted to take on American imperialism and British colonialism,” says Jacques. Winter winds howl through much of the film’s soundtrack, reminding us what a cold, unforgiving, and liminal place Quebec is—and also evoking the political gale that buffeted that distant era. Paul himself, in one of the tapes smuggled out of prison, refers poetically to “a wind no one can tame—this great drive, this great fervor within us. I feel it. Together we will create a hurricane.”

What is the ultimate effect and meaning of the storm that the Roses helped unleash? “Violence sickened them,” asserted the writer, socialist, and friend Jacques Ferron in an interview during Paul’s incarceration, “but they took direct action to move history forward.” Confidence regarding not only history’s eventual judgment, but also its own efficacy in driving history’s very mechanism, has always been a hallmark, even obsession of the Left, beginning with Marx himself. But did such would-be revolutionary groups as the FLQ move history forward? Those players who remain alive are uncertain. Jacques is alternately melancholic, emphatic, and at times nostalgic—laughing about a contretemps during his trial, when a melee erupted in the courtroom, the judge fled, and he was left holding his wig. “I thought I had scalped him!” he tells his nephew. Just so does time heal all wounds, alchemizing our rages into gleaming gems of memory, gratifying and baffling the revolutionary.