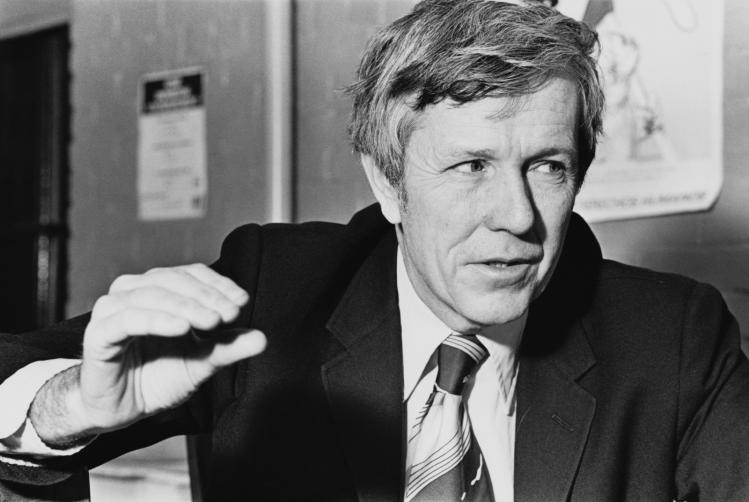

In February 1973, Michael Harrington convened a weekend conference on “The Future of the Democratic Left” at New York University. A hundred of his friends showed up to hear his pitch for a new organization. Most were refugees of the Socialist Party. A few were veterans of the New Left that skyrocketed and crashed in the 1960s and others were youths straight from the McGovern presidential campaign. They resolved to launch an organization modestly called the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee (DSOC). Harrington was a board member of Americans for Democratic Action who knew that most of its sixty thousand members were closet socialists, and so were many of the McGovern workers. He believed the United States had more socialists than ever; the mission of DSOC was to lure them out of the closet.

His charter statement for DSOC declared: “We identify with the tradition of Eugene Victor Debs and Norman Thomas—with a socialism which is democratic, humanist, and antiwar.” Harrington vowed that DSOC would have no doctrinal line and no cadre holding a vanguard pretention. His lecture tours built up DSOC, stressing that its pragmatic multiplicity embraced feminists, Fabians, democratic Marxists, gay-rights activists, Zionists, non-Zionists, pacifists, non-pacifists, former Communists, and environmentalists. He told audiences he was definitely some of these things and not others, but DSOC was emphatically all of them. He was religiously musical, albeit as a Catholic atheist, and thus welcomed religious socialists, who built one of the strongest DSOC commissions.

Many of us who joined DSOC in the mid-1970s came from colleges where the Old Left was unknown and the New Left never happened. It was puzzling to learn that Harrington had broken only recently from the Shachtmanite neoconservatives. He seemed nothing like the neocons who decried the McGovern campaign as an atrocity. Some DSOC stalwarts radiated Old Left Cold Warriorism, but not Harrington. The New Left, too, belonged to the past, a tale of youthful radicalism that crashed when we were in high school. We heard that a group of former Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) radicals had founded an organization in 1971 much like DSOC, the New American Movement (NAM). But it was confined to a few scattered strongholds. DSOC was a last shot at the historic Old Left dream of uniting the democratic Left, with Communists and anarchists left out.

Harrington’s stump speech during this period was titled “Liberalism Is Not Enough.” It commended the New York Times on civil rights, Richard Nixon, and the Vietnam War, and blasted the Times on economic justice, challenging audiences to cite any instance in which the Times supported a strike. He called the McGovern youth to battle for the soul of the Democratic Party in the “left wing of possibility.” On occasion Harrington made a Marxian point (“Here’s a note for Marxologists”), but he was careful to confine Marxian debates to his books and keep his sectarian past in the past. DSOC would not have succeeded had Harrington felt compelled to rehash either thing. I first heard his recruiting speech in 1974 at Harvard, where I co-founded a DSOC chapter, and first heard the introduction that always made him cringe. Harrington was introduced as the author of The Other America, “the book that launched the war on poverty.” He gently reintroduced himself: “I’ve written several other books that might interest you.” His other books were important to him, and he hoped they were better than The Other America, a puffed-up version of a journalistic article he wrote on the run during his Greyhound Bus years.

His big-book case for democratic Marxism, Socialism, was published the year before he founded DSOC. Four years later there was a sequel, The Twilight of Capitalism (1976), which Harrington dedicated to “the foe of every dogma, champion of human freedom and democratic socialist,” Karl Marx. Both books argued that Marx was a democratic socialist much like Harrington. To be sure, Marx was spectacularly wrong about the imminent implosion of capitalism, and some things he wrote fell short of championing human freedom. He mistook the takeoff of capitalism for its decline and wrongly predicted that workers would get poorer. As for the bad parts of Marx that Lenin seized upon, Harrington said they were temporary lapses, which Friedrich Engels compounded by grafting onto Marx his pet theory of dialectical materialism.

Much of Harrington’s argument rehashed signature tropes of Eduard Bernstein and the Social Democratic tradition. The opening line of the Communist Manifesto was absurd, with Europe in 1848 at war over bourgeois freedoms, not communism. Marx waxed hyperbolically about the specter of communism and the death of the bourgeoisie while advocating tactical alliances with Chartists in England, agrarian reformers in the United States, petty-bourgeois radicals in France, and the bourgeoisie itself in Germany. Then Karl Kautsky codified “orthodox Marxism,” which teetered on the contradiction between Marx’s apocalyptic vision of revolutionary deliverance and the tactical reform politics he espoused for the interim.

Nearly everything that Kautsky-Marxists and Bernstein-revisionists contested for decades traced back to whether they kept a two-house structure in place (Kautsky) or judged that Marx’s utopianism and denigration of liberal democracy compelled the democratic socialist corrective (Bernstein). Harrington was in the Bernstein tradition, but believed it was short on militant conviction and seriously underestimated Marx’s commitment to democracy. Both faults were evident before, and especially after, Leninism gained power and democratic socialists were compelled to oppose it.

Democratic socialists repudiated Marx’s doctrine of proletarian dictatorship and his claim that a proletarian revolution would abolish classes and the state. Harrington added that Marx was not an economic determinist, except on occasions when he was “unjust to his ideas.” Marx’s preface to the Critique of Political Economy (1859) contended that all intellectual, political, and religious phenomena are super-structural rationalizations of economic interests. Harrington said this formulation fell under the rule, “Even Homer nods.” The real Marx was the anti-mechanistic neo-Hegelian of the Grundrisse who taught that economics, politics, and culture intersect and mutually determine each other. Harrington was surely right that Marx, a profound and powerful thinker, was not a vulgar Marxist; the Critique of Political Economy oversimplified his argument by trying to summarize it concisely. But Marx published his preface in multiple contexts and did not publish the Grundrisse. Had Marx shared Harrington’s concern to absolve Marxism of economic determinism, he would not have recycled his formulation about it so determinedly, which supported his concept of class. Harrington did not believe the mode of production determined the organization of slave and feudal societies, but Marx emphatically believed it, defining a class precisely by its function in the mode of production.

Marx over-believed in the transforming power of proletarian democracy, failing to grasp the problem of bureaucracy that would bedevil every form of monopoly capitalism, social democracy, Marxism, and communism. Harrington stressed this problem and his indignation that Marx was constantly smeared as a Leninist totalitarian, especially by the Wall Street Journal, which Harrington read every day. He said the biggest problem with Marxism was that Marx trusted too much in democracy. Marx made errors large and small, but he saw in the struggling, hurting, ragged proletariat of the mid-nineteenth century the human builders of a good society. Reformist trade unions, of all things, were the cells of social revolution.

German sociologist Werner Sombart opined in 1906 that the United States was hostile to socialism because American prosperity prevented revolutionary consciousness from arising, the American economy had access to enormous natural resources, and American workers were obsessed with getting ahead; socialism might hold them back. Harrington countered that the United States had no deficiency of suffering and exploitation. Sombart’s famous brief for American exceptionalism made sense only in its immigrant context. Many immigrants found a better life in the United States after they fled from degrading conditions in their homelands. Moreover, America’s ethnic pluralism turned workers against each other and the introduction of labor-saving machinery set native-born skilled workers in the craft unions against unskilled immigrant laborers. Harrington lamented that the American Federation of Labor and the Socialist Party thus had anti-immigrant legacies, treating immigrants as the problem. American capitalism split the working class, and immigrant industrial workers stood outside the labor movement. American socialism never became what it should have been.

Socialism, to Harrington, was the idea of a society in which certain fundamental limitations of human existence are transcended—a vision of ample social goods being shared and enjoyed. The struggle for scarce resources programmed invidious competition into life, but in the modern age there is more than enough for everyone. The essential prerequisite for cooperation, community, and equality to become natural is the abolition of scarcity. Harrington resisted eco-apocalyptic projections for this reason. He believed that people do not respond generously to doomsday threats. Tidal, solar, and geothermal power, he would say, remain to be tapped; the benefits of space exploration are unknowable; modern assumptions about consumption are not immutable. Harrington was stubbornly optimistic in order to safeguard his premise that the means exist to create cooperative societies. Socialism cannot be created under conditions of scarcity. For socialism to be achievable, the battle for survival and the predatory culture of winning at the expense of others must be overcome.

DSOC projected a harder edge than the Thomas-era Socialist Party, though some DSOC Marxists objected that Harrington was no more Marxist than Bernstein and that his central trope—bureaucratic collectivism—did not come from Marx. Bureaucratic collectivism, to Harrington, was the defining feature and problem of late capitalism. The rise of late capitalism in the 1940s rendered obsolete the customary debate about economic planning. Planning, he argued, is a central feature of modern economies; what matters is the form in which it takes place. Corporate capitalism is a top-down form of bureaucratic collectivism in which huge oligopolies administer prices, control the politics of investment, buy off the political system, and define cultural tastes and values while obtaining protection and support from the state. It shakes down the state for subsidies and favors, and socializes its losses with government bailouts, all the while claiming to believe in private enterprise. Late capitalism vests managerial elites bent on increasing their own wealth and power with the power to shape the kind of society that everyone lives in.

DSOC built an advocacy organization called Democratic Agenda that played a major role in writing the 1976 Democratic Party platform. Two things enabled tiny DSOC to play an outsized role in Democratic politics: Harrington and DSOC were better than liberals at defending the welfare state, and DSOC had powerful union allies, especially AFSCME national president Jerry Wurf, AFSCME New York president Victor Gotbaum, UAW president Doug Fraser, and Machinists president William Winpisinger. These unions generously financed Democratic Agenda, showing that progressive unionism was real and growing. The centerpiece of Democratic Agenda was the Humphrey-Hawkins bill for full employment, modeled on the full employment bill of 1944. Humphrey-Hawkins committed the federal government to achieve an adult unemployment level of 3 percent or less. In 1976 Jimmy Carter won the Democratic presidential nomination and left-liberals went to work on him. Carter delivered a liberal speech at the Democratic Convention, named Minnesota liberal Walter Mondale as his running mate, and told his platform operator Joe Duffy to accommodate the Democratic Agenda caucus. He ran on Humphrey-Hawkins and a pledge to limit defense spending, defeating Gerald Ford in November.

Harrington claimed that Carter owed his victory to the coalition of unionists, Blacks, Hispanics, feminists, and liberals represented by Democratic Agenda, but Carter drew a different conclusion, having won ten of the eleven former Confederate states. He believed that being an outsider was the key to his election and presidency. Thus he took pride in his bad relationship with a Democratic Congress, counting it as evidence of his virtue. Carter was a moralistic-technocratic throwback to the pre-New Deal Democratic Party, albeit with updated views about racial justice, feminism, and human rights. DSOC and the labor movement seethed that Carter did almost nothing to stem a tidal wave of layoffs, plant closings, and union busting. The economy slid into a miserable recession and a chorus of liberals joined Harrington in imploring Carter to enact the Keynesian policies he ran on.

In 1978 Harrington and Fraser organized an anti-Carter challenge at the Democratic Party midterm convention in Memphis. They blasted Carter’s entire record while young Hillary Clinton whipped a floor vote to prevent the party from censuring its incumbent president. This convention augured Sen. Edward Kennedy’s primary challenge against Carter. Harrington and Kennedy were friends, and Harrington dreamed of riding into power in Kennedy’s administration. Kennedy challenged Carter for the nomination, DSOC went full bore for Kennedy, and Kennedy ran a strange, timid, vacuous campaign, deflating DSOC. Carter won the nomination and DSOC refused to slink back to him. Harrington could not muster his usual appeal about the lesser evil and holding your nose. He was too disgusted with the odd, isolated, tone-deaf Carter to try.

As much as Harrington despaired over Carter’s bad luck and failure, he realized that both reflected the structural crisis of the welfare state. Rational-choice Marxism had its heyday during this period, proposing to explain the combination of stagnation and inflation that blighted the Carter years. G. A. Cohen, John Roemer, and Jon Elster described welfare-state capitalism as a structural conflict among capitalists, state managers, and workers in which each group rationally maximizes its material interests. State managers provide public services and impose regulations up to the point that capitalists allow, but capitalists have the upper hand because the legitimacy of the managers depends on the health of the economy. State power is exercised within class configurations that condition how it is exercised. Harrington resisted the vogue of rational-choice Marxism because its vaunted “rationality” tied the interests of classes and state managers to capitalist structures. If a state manager’s self-interests define what rationality means, and the state is free, how is this a Marxian theory of the state? Rational-choice Marxism was great at winning perches for Marxists in the academy, but stripped Marxism of its distinct power—Marxian dialectic. Harrington judged that the entire rational-choice school was too individualistic. Real Marxism takes the class struggle more seriously than rational-choice Marxism.

California State University political economist James O’Connor was more helpful to Harrington. In The Fiscal Crisis of the State (1973), O’Connor argued that the growth of the state sector is a cause of the expansion of monopoly capital and an effect of its expansion. As technology advances and production becomes specialized, big firms swallow small ones, creating an economy that is more difficult to regulate, facilitate, support, clean up, and bail out than the economy of smaller enterprises it replaced. O’Connor stressed that, in welfare-state capitalism, nearly every state agency performs accumulation (sustaining or creating the conditions for profitable capital accumulation) and legitimization (sustaining or creating the conditions for social harmony) functions, and nearly every state expense has a corresponding twofold character. Social insurance reproduces the workforce, while income subsidies to the poor pacify what Marx called “the surplus population.” Against conservatives, O’Connor showed that the growth of the state is indispensable to the expansion of capitalism, especially the monopoly industries. Against liberals, he denied that the expansion of monopoly industries inhibits the growth of the state.

O’Connor said this accumulation of social capital and social expenses is a contradictory process yielding the fiscal crisis of the modern state. The state that increasingly socializes capital costs does not appropriate the social surplus. Welfare-state capitalism is about capitalists socializing their losses and keeping the profits. The fiscal crisis is the upshot of the structural gap between state expenditures and state revenues. Expenditures increase more rapidly than the means of financing them. Some special interests are litigated in public view, especially whatever unions and the poor request, and others are carefully screened from public view. In both cases, the market is almost never the coordinating agency. Special interests are processed by the political system and either succeed or fail there, yielding the staggering waste and duplication of welfare capitalism.

This analysis and a similar Germany-based account by Frankfurt School socialist Claus Offe undergirded Harrington’s analysis of the social costs of late capitalism. The government is charged with arranging the preconditions for profitable production, and its rule depends on its success in doing so. The capitalist state is not capitalist, so it depends on capitalists. Every public servant works for the benefit of monopoly interests. Like O’Connor, Harrington lingered over the labyrinthine process that produces a federal budget, cautioning that its pro-corporate outcome is only partly explained by the political power of corporations and the rich. Government acts as the representative of the capitalist class as a whole, something no enterprise can do. Marx famously described the democratic state as the executive committee of the bourgeoisie. Harrington said this is a true insight into the function of the state under late capitalism. The anarchic and competitive capitalist class must be more discrete in democratic societies than was true in Marx’s time. Under late capitalism, the state plays the indispensable role of articulating a unifying national interest and ideology that transcends all business rivalries. The U.S. state sustains the functional illusion that all Americans have equal opportunity, freely choose their work, and freely choose their rulers.

Harrington departed from O’Connor on one point. O’Connor said unions are completely co-opted, enabling monopoly capital to export capitalist conflicts to the small-business and state sectors. Union wage increases in the monopoly sector are passed on to the society, while big business and big labor share the benefits of social investments, social consumption, and defense outlays. Corporations are hostile to government production of goods or services, while unions are not, but otherwise, the relationship between big business and big labor is a partnership. Any plausible resistance to capitalism must come from alliances of teachers and administrators, transport workers and transit users, welfare workers and welfare recipients, and the like. Autoworkers, steelworkers, and other big unions were hopelessly lost to the struggle for justice, having bonded with monopoly capital.

Harrington refused to believe it. To be sure, the welfare state is systematically biased in favor of monopoly capital. The game is rigged and the state is deeply implicated in it; the case for fatalistic resignation is awfully strong. But Harrington insisted that the welfare state is more dialectical and complex than O’Connor said. It matters that progressive unions exist. The union struggles of the 1930s helped to build the New Deal and the industrial unions. The welfare state, Harrington contended, will never produce anything more than very limited concessions to the needs of the vast majority. Almost nothing that Left-liberals want in the economic arena can be achieved without mobilizing progressive unions. Price controls on oligopolies, universal health insurance, quality education, full employment, redistribution of wealth and income, and a minimum guaranteed income are out of reach if big labor rests content with sharing the spoils of monopoly capitalism. The spoils, however, were diminishing in 1980, which ruined Carter’s presidency and yielded the election of Ronald Reagan, a fire alarm crisis for the democratic Left.

DSOC came from a decade that never quite began. In historical-political terms, there were no 1970s. The 1930s belonged to Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal, which extended through Harry Truman’s surprise victory of 1948, holding off the Republican attempt to end the Roosevelt era. Dwight Eisenhower clearly stamped the 1950s as a political era, and the 1960s were also dramatically marked off (though Harrington, waxing on this theme, always said there were two 1960s, divided by 1965). Nixon blew his chance to stamp the 1970s and Carter was too ineffectual even to try. Nixon owed his presidency to the backlash against the 1960s and Carter owed his presidency to being a moralistic contrast to Nixon. The backlash reached full throttle in 1980, electing Reagan. The 1980s turned the 1960s upside down, though Harrington insisted until his death in 1989 that the 1980s were simply another lost decade that would soon be left behind in memory and feeling.

Carter spent the last days of the 1980 campaign trying to awaken a sense of revulsion about Reagan, reminding Americans of his ugly opposition to the civil-rights movement. That was futile; the overwhelming majority that elected Reagan was finished with feeling bad about African Americans, Vietnam, the poor, and America. Reagan heaped vile ridicule on women of his imagination—the so-called “welfare queens.” He told Americans their country was in economic decline because labor elites strangled productivity, liberals created government jobs for themselves, and poor mothers were addicted to welfare. Liberals coddled America’s criminal class (coded Black) and welfare class (also coded Black). The poor became “the underclass,” another coded term meant to repel. The word “liberal” became an epithet in American politics. Neocons took high positions in Reagan’s administration and appointed more neocons under them.

Supply-side economics, popularized by New Right writer George Gilder, rationalized Reagan’s fiscal policy. It was a pure fantasy championed by economist Arthur Laffer, Wall Street Journal editorial writer Jude Wanniski, and House Republican Jack Kemp. The “Laffer Curve” supposedly showed that massive tax cuts would generate far more revenue than they lost. For a half-century, Republicans had scolded that Democrats were bad because they handed out a free lunch at taxpayer expense. Republicans were the party of responsibility and Democrats were the party of irresponsibility. Reagan turned this tradition on its head by embracing the magical world of supply-side deliverance. Now Republicans offered a free-lunch bonanza to taxpayers, especially the rich. Everybody except the poor would get something and the tax cuts would generate a historic windfall of economic growth. The Reagan White House had to forecast how the economy would develop as a basis for calculating its proposals. Supply-side advisors wanted a very high figure for real growth in gross domestic product (GDP) in order to prove that their proposals worked. Monetarists wanted a low “in money” GDP (real GDP plus the rate of inflation) to prove that their policies held down prices. The two camps figured out what would have to happen to make their contradictory policies come true; then they claimed it would happen. This unhinged mentality tripled the nation’s debt in eight years. Every prediction of the Reagan White House failed, except the political one that tax cuts are wildly popular.

Reagan led the Republican Party and a host of enabling Reagan Democrats into temptation by persuading both that deficits don’t matter because tax cuts more than pay for themselves. Reagan cut the marginal tax rate from 70 percent to 28 percent, cut the top rate on capital gains from 49 percent to 20 percent, and dramatically hiked military spending—an additional 4 percent increase on top of the 5 percent increase for 1981 authorized by Carter. This staggering splurge of social engineering fueled a huge inequality surge, which Reagan officials described as a return to the economic state of nature. The promised trickle-down effect of Reaganomics never materialized because only corporations and the wealthy gained new disposable income.

Harrington grappled anxiously with the stagflation, uneven growth, and threats to the welfare state that were the legacy of the 1970s. He said he felt closer to free-enterprise conservative Friedrich Hayek than to liberals because Hayek understood that the prosperity of the 1950s and ’60s was not coming back, while liberals refused to believe the world had changed. Hayek claimed the New Deal violated eternal laws of economics, eventually reaping what it sowed. The crisis of the 1970s and ’80s was the natural free-market punishment for Keynesian hubris. Harrington acknowledged that liberalism collided head-on with the structural limitations of the system it improved. Working- and middle-class Americans no longer expected to live better than their parents.

In May 1981, Harrington’s friend François Mitterrand was elected as the first Socialist president of France’s Fifth Republic. He enacted his entire campaign program, nationalizing banks and key industries, increasing social benefits, instituting a 10 percent increase in the minimum wage, and enacting a solidarity tax on wealth. He sought to boost economic demand and achieve full employment with a stimulus designed to help the poorest the most. But the economy stagnated, unemployment worsened, the Bank of France maintained a stringent monetary policy, and the franc was devalued three times. Mitterrand began to retreat in 1982. In March 1983 he caved entirely, imposing austerity policies that wrung inflation out of the economy.

In political terms, Mitterrand’s adjustment worked. He had a respectable run as a social democratic manager, winning reelection in 1988 and remaining in office until 1995. Harrington, however, was chastened by the spectacle in France. Nationalizing the banks did not help and neither did Mitterrand’s Keynesian stimulus. Harrington said the only nation where Mitterrand’s aggressive approach might have worked was the United States, but it instituted Keynesianism for the rich instead. He did not claim that Mitterrand should have stuck to his convictions. The world was going through a wrenching transition that couldn’t be helped. What mattered was to limit the harm to workers and the poor.

For two years, Reagan presided over worse misery than anything that Mitterrand could stand or survive. Liberals crowed that Reagan was sure to be a one-term failure like Carter. Harrington warned in November 1982 that Democrats were overconfident and shortsighted. Lower wages, reduced inflation, lower interest rates, fear of unemployment, and shuttered plants might combine to revive the economy just in time to reelect Reagan. Harrington’s prediction was borne out after the defense buildup and consumer spending on credit kicked in. Unemployment was down to 3.5 percent when Reagan crushed Walter Mondale in 1984. Mondale was scorned as a tax-and-spend liberal and for warning about Reagan’s deficits and militarism. Harrington rued that Mondale united all the forces in the Democratic coalition and still got blown away by a brief recovery. It hurt worse than Carter losing, because Mondale was a good candidate.

“We never said the welfare state is a substitute for socialism.” This staple of Harrington’s lecture tours had a flipside, his retort to old-school socialists: “Any idiot can nationalize a bank.” He said both things frequently after Mitterrand retreated. Harrington relied on his core message: bureaucratic collectivism is an unavoidable reality. The question is whether it can be wrested into a democratic and ethically decent form. Freedom will survive the ascendance of globalized markets and corporations only if it achieves economic democracy. Harrington had long argued that the market should operate within a plan, but in the mid-1980s his actual position shifted to the opposite. He conceived planning within a market framework on the model of Swedish and German social democracy—solidarity wages, full employment, co-determination, and collective worker funds. To many critics that smacked of selling out socialism. He replied: “To think that ‘socialization’ is a panacea is to ignore the socialist history of the twentieth century, including the experience of France under Mitterrand. I am for worker- and community-controlled ownership and for an immediate and practical program for full employment which approximates as much of that ideal as possible. No more. No less.”

In 1982 he welcomed a merger between DSOC and NAM that created Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). NAM made important contributions to socialist feminist theory and to the Gramsci boon of the 1970s. DSA became a better organization than DSOC had been, but DSA accentuated the old DSOC problem of uniting activists primarily devoted to feminism, anti-racism, gay and lesbian rights, anti-militarism, labor, Third World solidarity, religious socialism, environmentalism, and other causes. It featured even less of a distinct socialist perspective than DSOC had managed. DSA stressed the interconnectedness of economic justice, cultural recognition, anti-militarism, and ecology. Cornel West was one of the newcomers to the merged organization. He said he joined DSA because he needed to belong to some organization that cared about everything he cared about. That was the best argument for DSA, but there were never enough people who felt that way.

Harrington and former NAM writer Barbara Ehrenreich became co-chairs in 1983, with mixed results at best. Many of us puzzled over and regretted the aversion between them, delicately steering around it. Ehrenreich wrote astute, wonderfully snarky op-eds on politics and culture; one of her collections was titled The Snarling Citizen (1995). She helped DSA survive the wilderness years with pluck and humor. Many DSA members were volunteer workers in Jesse Jackson’s Democratic primary campaigns of 1984 and 1988; I was one of them. Harrington was skittish about Jackson in 1984 because electing Mondale seemed imperative. Afterward Jackson won him over and Harrington wrote speeches for him in 1988. Jackson tried to build a Rainbow Coalition of social movements that outlasted the election cycle. Many of us Jackson volunteers worked harder for Mondale in the general election than we managed four years later for Michael Dukakis; others dropped out completely by then. We did not talk about realignment except to say that we no longer believed in it. Even Harrington said there were no political parties anymore. Hollowed out “dealignment” was the reality, organized anarchism. Political adventurers roamed the countryside to build their personal following, armed with state-of-the-art technology, battling each other like warlords. When they won they tried to govern by patching together ad hoc coalitions. Harrington believed that dealignment would eventually throw the entire system into a crisis. He didn’t claim to know what would happen next. He said he just wanted democratic socialists to be ready to be relevant.

In 1985, Harrington learned he had metastatic carcinoma, a secondary growth indicating that he had a serious primary cancer lurking somewhere, which was found at the base of his tongue. Harrington underwent treatment and had a successful operation. For two years he returned to road lecturing. The Youth Section was active in the Central American and South African solidarity struggles, and in 1987 a DSA-led coalition called Justice for All held rallies, teach-ins, and press conferences in more than one hundred cities protesting against cuts in Medicaid, food stamps, welfare, and federal aid for housing. Harrington had reason to believe that DSA was doing reasonably well despite everything, though sometimes he read too much into drawing a big crowd.

Harrington found out in November 1987 that he had a new and inoperable tumor in his esophagus. He vowed to write a capstone book, and the following June his friends organized a sixtieth birthday celebration at the Roseland Dance Hall in New York. Edward Kennedy, William Winpisinger, Gloria Steinem, Cesar Chavez, and Canadian Socialist leader Ed Broadbent spoke. Kennedy lionized his ailing friend. Harrington responded with his favorite set piece, the water parable. In desert societies, he said, water is so precious it is money. People fight and die for it; marriages are arranged to secure it; and governments rise and fall in pursuit of it. Entire societies stretched over several millennia have taken for granted that fighting over water is ingrained in human nature. Many such deserts still exist, deeply conditioning the human beings that live within them. Yet in modern societies we expect not to die of thirst: “Water is the one thing that has been socialized. Hoarding it, fighting over it, marrying for it are not part of human nature after all—because we have confidence that it will be shared. So why can’t we go a little further and imagine societies in which each person also has food and shelter? In which everybody has an education and a chance to know their value? Why not?”

His last book, Socialism: Past and Future (1989), expounded his signature trilogy of points: first, socialism is the hope of human freedom and justice under the conditions of bureaucratic collectivism; second, the fate of freedom and justice depends upon social and economic structures; and third, capitalism subverts the possibilities of freedom and justice that it fostered—unless it is subjected to democratic control from below. Harrington fastened on the contradictory meanings of “socialization” and the ambiguous legacy of Marx related to them. Marx caught the crucial contradiction of capitalism by describing it as private collectivism. Capitalism is an anti-social form of socialization that began by expropriating the labor power of the individual. Peasants were driven from their land, artisans were deskilled, and a regime of collective property replaced individualistic private property in the name of securing it. To be sure, Marx over-believed in contradiction dialectics, contending that capitalism would abolish itself after it abolished feudalism, but Marx was right about capitalism destroying its own best achievement. Harrington’s last book updated his argument that late capitalism subverts freedom and justice by enlisting the state to subsidize its interests, socialize its losses, and protect the rule of elites.

Socialization can refer to the centralization and interdependence of capitalist society under the control of an elite, or to bottom-up democratic control. Harrington wanted to say that socialization is really only the latter, while the former should be called “collectivism.” But that would be misleading, since both terms have varied historical meanings. Socialization can mean different things. Reagan employed the power of the state to carry out a class-based reduction of taxes to subsidize a rich minority. He used social power on behalf of an elite, but it would be strange to describe Reaganomics as collectivism. On the other hand, state ownership suited the socialist movement in only one brief phase of its history, between the two World Wars.

Good socialism is about empowering people at the base. Capitalism has created societies in which hardly anyone in the working class believes their work has a positive value. Harrington commended the feminist and ecology movements for relieving the Left of its traditional focus on the workplace, but he still viewed the human experience of work as central to economic justice. New technologies were creating new kinds of work that demand re-skilled workers and new kinds of workplaces. Harrington began to write his last book on the day he was told his cancer was inoperable. Socialism: Past and Future was a letter to the next Left.

Harrington said the world desperately needs socialism to have a future. Only socialists have a record of caring about everybody in entire societies and the world. Socialists do not let go of demanding freedom, equality, and community for everyone. He denied that his conception of socialism was insufficiently radical. Only a socialism construed as visionary gradualist pressure has any chance of democratizing bureaucratic collectivism.

Today this is a minority position in DSA. Many who surged into the socialist Left in recent years moved straight to one of its ultra-left ideologies. Revolutionary state socialists and anarchist-libertarian socialists are radically opposed to each other, but agree that Harrington-style gradualism is much too tame and modest. They point to the capitulation of European Social Democratic parties to neoliberalism, and to the SPD propping up four Conservative Merkel administrations in Germany. They are right on both counts, but there is such a thing as a social democratic socialism that fights for economic democracy. Harrington exemplified it to the end of his days.

The present article adapts material from the book American Democratic Socialism: History, Politics, Religion, and Theory, forthcoming in September 2021 from Yale University Press.