This article first appeared in the December 20, 1935 issue of Commonweal.

I wish the subject I discuss here in a short article could be discussed in a big book, or a long series of books. I rather fancy that, if it could really be reduced to its elements, we should find the elementary truth about Catholicism and Protestantism and the present problem of our civilization. It would perhaps explain why, in the coming Christmas, many millions of our mature fellow creatures, so far from hanging up their stockings to have them filled, will rather hang up their hearts and heads and find them empty; and why they will continue to enact a fable for children to believe in, and for children who do not believe in it. For the sake of brevity, let me sum up such a scientific monograph under the heads of three or four questions.

First, who was Santa Claus, or who was he supposed to be? Why do we actually describe this domestic and familiar figure by a name in a foreign language that few of us know? Why should a sort of uncle or grandfather so intimate that he is allowed to enter by the chimney, instead of the front door, have on his visiting-card the rather florid name of a distinguished foreigner? The answer is important. It is because in my country the saints really have crept back again like spies. St. Nicholas of the Children may not come through the chimney like a burglar; but he was really admitted through the front door only as a foreigner. It is part of a paradox, that Protestant England satisfied its intense insularity mainly by the use of foreign words. For instance, men cannot do without the image of the Mother of God; the veritable Queen of Hearts, with every sort of lovers in every sort of land. But the Victorians got over her omnipresence in all art by calling her “a Madonna,” whatever that may mean. As it was British to talk of Mary only in Italian, so it was British to talk of St. Nicholas only in German. So we could tap all the traditional poetry of Christendom, without calling it Catholic or even Christian. It was a sort of smuggling; we could import Nicholas without paying the tax to Peter.

Second, everybody could then dispose themselves in elegant attitudes of sad sympathy and patronizing pity over a mere fairytale for children, which children themselves must soon abandon. Santa Claus has passed into a proverb of illusion and disillusion. A man wrote a poem about how he had ceased to believe in Santa Claus at the age of seven and in God at the age of seventeen; and explained how he really regretted God not much more than Santa Claus. The notion that the thing had ever had any relation to any religion, or that that religion had ever had any relation to any reason, or that it had been a part of a real philosophy with a fringe of popular fancies but a body of moral fact, never occurred to anybody. And I startled some honest Protestants lately by telling them that, though I am (unfortunately) no longer a child, I do most definitely believe in Santa Claus; though I prefer to talk about him in my own language. I believe that St. Nicholas is in heaven, accessible to our prayers for anybody; if he was supposed to be specially accessible to prayers of children, as being their patron, I see no reason why he should not be concerned with human gifts to children. I do not suppose that he comes down the chimney; but I suppose he could if he liked. The point is that, for me, there is not that complete chasm or cutting off of all relations with the religion of childhood, which is now common in those who began by starting a new religion and have ended by having no religion.

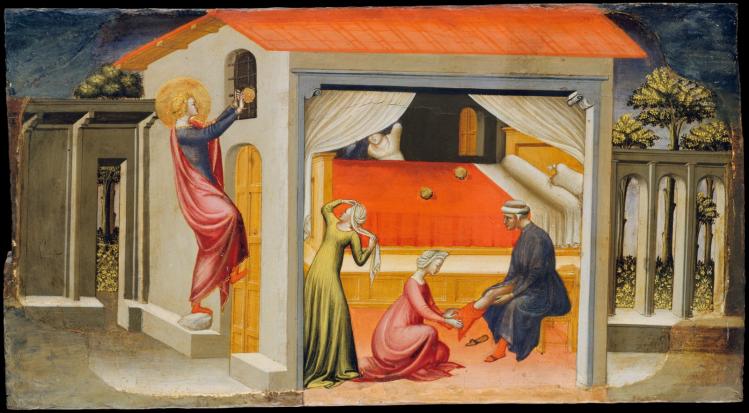

Third, do our contemporaries really know even the little that there is to know about the roots, or possible origins, of such romances of popular religion? I myself know very little; but a really complete monograph on Santa Claus might raise some very interesting questions. For instance, St. Nicholas of Bari is represented in a well-known Italian picture of the later Middle Ages not only as performing the duty of a gift-bringer, but as actually doing it by the methods of a burglar. He is represented as climbing up the grille or lattice of a house solely in order to drop little bags of gold among the members of a poor family, consisting of an aged man and three beautiful daughters who had no money for their wedding dowries. That is another question for our contemporaries: Why were celibate saints so frightfully keen on getting other people married? But anyhow, I give this only as one example out of a hundred, which might well be followed up if only grown-up people could be induced to take Santa Claus seriously. It looks as if it might be the root of the legend. To see a saint climbing up the front of our house would seem to most of us as odd as seeing a saint climbing down our chimney. Very probably neither of the things happened; but it might be worthwhile even for scientific critics to find out what actually did happen.

Fourth, what do our great modern educationists, our great modern psychologists, our great makers of a new world, mean to do about the breach between the imagination and the reason, if only in the passage from the infant to the man? Is the child to live in a world that is entirely fanciful and then find suddenly that it is entirely false? Or is the child to be forbidden all forms of fancy; or in other words, forbidden to be a child? Or is he, as we say, to have some harmless borderland of fancy in childhood, which is still a part of the land in which he will live; in terra viventium, in the land of living men? Cannot the child pass from a child’s natural fancy to a man’s normal faith in Holy Nicholas of the Children, without enduring that bitter break and abrupt disappointment which now marks the passage of a child from a land of make-believe to a world of no belief?