Nothing in the long and tragic history of Catholic anti-Jewish action rivals the blood libel for shock, horror, and folly. The sudden disappearance of a Christian child in a small rural Central or Eastern European town is met, unexpectedly, by an outburst of accusations by local Christians against their Jewish neighbors. Good men and women who have lived peacefully for decades suddenly hear themselves accused of abducting and murdering a small child for the purpose of religious sacrifice. The blood libel has been around since the twelfth century, fostering in Christians the feeling that they are once again the victims of Jews, hence justified in defending themselves, their faith, and their children against the ancient enemy.

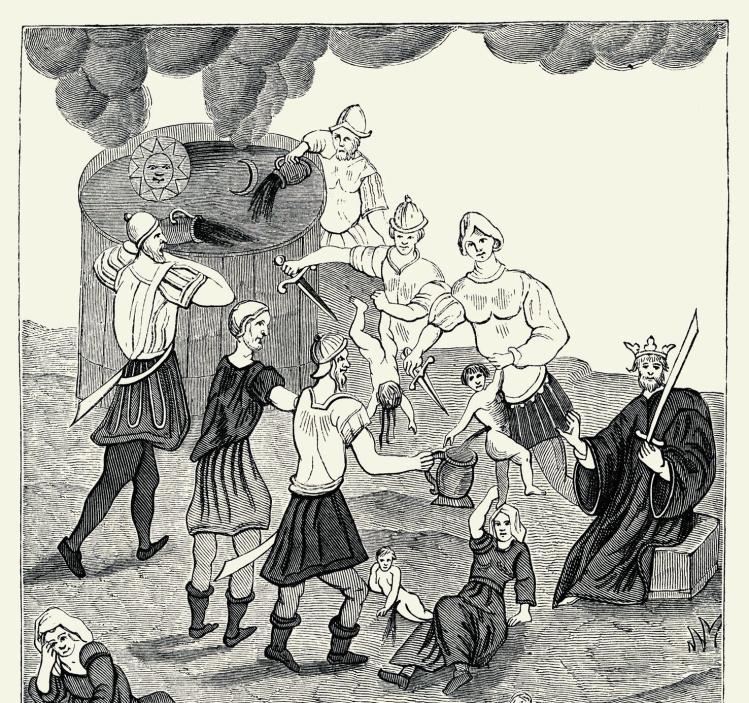

In truth, ritual-murder accusations took hold only rarely: fewer than a hundred noteworthy cases in a millennium. And such charges almost invariably provoked some degree of disbelief among the educated and those in authority, as well as refutations from the learned—Christian or Jewish. Formal investigations and trials were authorized despite ambivalence and reluctance on the part of doubtful officials. Indeed, the case that proved to be the “big bang” of blood-libel notoriety involves Simon of Trent (1475), which exploded into high visibility mainly because secular and religious authority was united in the hands of a powerful prince-bishop who found it politically expedient to pursue this case. He did this so efficiently that Rome felt obliged to acquiesce: Simon was eventually canonized, while books about “the martyr” were still being churned out more than four centuries later in justification of the blood libel.

Tendentious books of blood libel went uncondemned by the magisterium, transforming fake news into established tradition, a long “memory trail.” Those in search of a pretext could always find phony documentation to justify their chimerical beliefs about Jews. “This long story of the persistence of anti-Jewish blood libels despite arguments to the contrary is dispiriting,” concludes Magda Teter in Blood Libel: On the Trail of an Antisemitic Myth, a long-awaited study of ritual-murder accusations. Teter, a professor at Fordham University, shows that the “great” medieval cases of William of Norwich (1144) or “Little Hugh” of Lincoln (1255) took on celebrity status only centuries later in the sinister retroactive light shed by Simon of Trent. Teter also shows that the blood libel, even as it arose in very Catholic Poland, did not turn on matters theological (e.g. the Crucifixion) but consisted of vitriolic efforts to brand Jews as criminals or perpetrators of anti-Christian cruelties in order to impede their social interaction with Christians. (The attempts did not always work: in Eastern Europe, as in Central or Western Europe, Jews and gentiles got along well for the most part.)

If the Reformation and Enlightenment largely put the kibosh on German, French, and British blood-libel charges, the Counter-Reformation gave the lie new life as a popular discourse in Poland–Lithuania. A report prepared by Cardinal Ganganelli (the future Pope Clement XIV) in 1758 concluded that ritual murder was a calumny void of truth, but this text lay buried in the archives for more than a century. It was printed for the first time around 1900 because the blood libel, having receded from visibility for three centuries, underwent a stunning revival in five shocking cases. Teter does not include Tiszaeszlár (1882–3, Hungary), Xanten and Konitz (1891–3 and 1900, respectively, both Germany), Hilsener (1899–1900, the Czech lands), and Beilis (1913, Russia) in her study, though she does have a postscript on them. They are covered with great detail in another recent book: Blood Inscriptions: Science, Modernity, and Ritual Murder at Europe’s Fin de Siècle by Hillel J. Kieval, a professor at Washington University.

Teter and Kievel are both accomplished and respected scholars, yet in critical points of method, interpretation, and understanding, they sharply differ in their approach to the topic—a reminder, if one were needed, that history is always as much an art as a science. Had Teter chosen to “finish the story” with a hundred pages of analysis of the modern cases, one suspects she would have turned out a study very different from Kieval’s.

Teter’s is a sweeping work of longue durée, from the mid-twelfth to the late eighteenth century throughout Europe. While much changes, the continuities prevail over the discontinuities. Her book is, most importantly, a study where religion is the final reference point, notwithstanding numerous learned peregrinations into the adjacent terrains of society, economy, and politics. For Teter, the ritual-murder accusation has a clear and stable identity from its earliest appearance to its most recent. In fundamental ways, the Beilis case in 1913 rehearses the William of Norwich case in 1144, thanks to nearly eight centuries of Christian anti-Jewish discrimination, persecution, and contempt in sermons, rites, policies, and public sentiment.

Kieval, on the other hand, has produced a micro-history focusing on five locales in Central Europe over thirty years. In his telling, modern ritual murder is a new phenomenon that relates only nominally to the earlier cases Teter focuses on. In this, Kieval follows the prevailing scholarly view, according to which “antisemitism” constitutes a thorough-going departure from religious anti-Judaism. Kieval’s conclusions about the novelty of latter-day ritual murders are anchored in his analysis of his subjects’ distinctively modern epistemology, which embraced the secular languages of forensic science, politics, and “breaking news” journalism. In other words, their understanding did not turn on theology, and they were not concerned with the religious symbolism of the alleged crimes: Jesus was no longer being “crucified.” Instead, the modern version of the blood libel accused kosher butchers of slicing up Christian children for no particular reason beyond, in Kieval’s pungent words, “raw brutality…. [S]acrifice has been transmuted into slaughter, the altar into the cutting block…. The Jews, themselves, finally, are not religious adversaries, the vanquished recipients of the Old Law; they are Yids.”

“This is not a book about the tenacity of myth and superstition in the modern world,” Kieval writes. He posits no “cultural backwardness” or “atavism” in the antisemites he studies. They were not seduced by some “irrational element in the blood libel”; there was no breakdown of Enlightenment understanding. In short, he finds no “regrettable continuity between the medieval accusation and its modern variant.” He concedes that he had once thought differently, believing that modern antisemitism represented an explosion of “irrationality in the Weberian age of disenchantment.” But no longer: immersion in the language of officials, police, lawyers, doctors, and experts disabused Kieval of this idea, for they all viewed events through modern glasses and understood them through modern scientific categories. The “modern trial for ritual murder” has “unique features,” he writes, and constitutes not only “a new phenomenon in the long history of the blood libel [but] a new chapter in Jewish-state relations.”

Kieval’s accounts of the five stories of modern ritual murder do not unfold quite as smoothly as we might expect. At every stage of every trial in Hungary, Germany, or Bohemia, premodern language—explicit or vague charges of ritual murder—swirled and eddied throughout the town, as locals not previously known to be Jew-haters took up the cry that a Jewish neighbor had abducted a young Christian for his or her blood. Kieval calls this the “disreputable” language of tradition; it cascaded throughout the ensuing trial and media circus and ran up against the more “reputable” language of science. Indeed, hoary tradition often got the jump on modernity, appropriating legal and forensic developments to its own ends.

The drawn-out “affairs” Kieval writes about could last for as long as two years, occasioning large riots, extensive property destruction (including to synagogues), and harm to people. These episodes often required authorities to dispatch substantial army units to restore and maintain order. Kieval’s book makes for a tense reading experience, as we wonder whether rational idioms and rules of expression will finally prevail in the great battle for control of interpretation. Frequently, they do not. Discussing Konitz, for example, Kieval remarks on the amount of time that members of the prosecution were “misguided—led astray by explicit and implicit bias, rumor, the power of suggestion.” As time passed, “the legal and scientific discourse of Jewish ritual murder became increasingly ‘illegible,’ even as anti-Jewish emotions appeared to be gaining in strength.”

Kieval’s intricate picture of a “naturalized” blood libel, stripped of all obvious religious symbolism, is brilliantly rendered and important. The high faith of 1200 and the low superstitions of 1890 took very different forms, and Kieval is right to insist on the importance of the changes. On the other hand, most aspects of human life—from science and statecraft to law and sewage disposal—changed radically between 1200 and 1890. Yet it is another question whether these changes transformed them into different things entirely. Ancient sacraments are still holy; Good Friday today is still closer to the original day of the Crucifixion than to any midsummer’s day, as Charles Taylor notes in A Secular Age. So, is Kieval right that no “continuity [exists] between the medieval accusation and its modern variant”?

Scholars pore over the medieval origins of the modern state and nation. So why do recent generations of historians of modern antisemitism dispute the relevance of a “deep” past (as a previous generation of scholars, from Baron to Katz to Yerushalmi, did not)? It is difficult to find another area of scholarship where historians, of all people, proceed by burying the significance of the past rather than exhuming it. The impulse to reduce modern antisemitism to its racial, economic, social, and political factors may, in truth, be inseparable from the impulse to lay out a new academic field for cultivation, a field distinct from the endless forests of anti-Judaism in theology, literature, philosophy, folklore, and you-name-it. It has the appeal of offering a “specialty,” permitting archival mastery of a fathomable subject. One can thus study examples of anti-Jewish behavior in a given place during a limited period—and keep it there. The practitioner is freed from having to juggle many balls at once.

The reticence to adduce deep historical causes for modern antisemitism may be due in part to the sticky matter of religion. That subject is just too old-fashioned and complicated: religion’s busy afterlife in unbelieving ages, the varieties of so-called secular religions, etc. Even the most desultory inspection reveals to the unsuspecting contemporist that what he had dismissed as a monolith—defunct orthodox religion—is actually a moving kaleidoscope of shifting forms, very much affecting “secular” ages. Whatever his reasons, Kieval staunchly walls off modern ritual murder and the antisemitism that embraced it from “eternal anti-Judaism.” By doing so, he takes the antisemites at their word when they deny religious motivation and insist on “purely secular” reasons for their persecution of Jews—this despite the fact that he warns his fellow historians against an uncritical acceptance of sources.

After fifteen years of studying “modern” antisemitism, I have concluded that nothing is more definitive of antisemitism than the false claim that it is free of religion. Not recognizing this is akin to accepting the argument “but many of my friends are Jewish…” For the historian to look away from religion because he deems it old hat is to fail to see the subtle ways in which religion suffuses antisemitism in general and charges of ritual murder in particular.

Historians are like film editors; the best of them leave a lot of the actual footage on the cutting-room floor. What Kieval minimizes in favor of “scalpels, micrometers, microscopes, and the scientific prestige they wielded” is the common fare of most histories of these five episodes (and there are many)—to wit, the cascades of accusations that ritual murder is “ordained” in the Hebrew scriptures. To sift the era’s press reports and commentaries, and not only the antisemitic ones, is to wander in a thicket of the kind of premodern language and assumptions that Kieval describes as “disreputable.” There were clerics who knew better—for example, Rev. Stoecker, court preacher to the German Kaiser—but nevertheless purveyed the blood libel, and there were clerics who did not know better—for example, Josef Deckert, an Austrian priest who wrote books on the veracity of blood libel, from Simon of Trent to Hilsner. There were skeptical politicians such as Mayor Lueger of Vienna who disbelieved but transmitted the blood libel anyway; they were joined by racists and anticlericalists who hated religion but nodded in sage agreement with the “good Christians” in Konitz rioting against the “child killers.” Is it any wonder that Ismar Schorsch, a respected historian of an earlier generation, laments that “medieval animosity toward Jews” was not dissipated but “sustained, transmuted and intensified”?

Those who propagated accusations of ritual murder at Xanten and elsewhere were not troglodytes; they used electricity and clocks, and knew the earth was round. But many—it is all but impossible to know their precise number—simultaneously believed in dark fantasies where the Jews were concerned. As for the cynical and opportunistic antisemites who knew these were fantasies, they arrived in town only after the scandale was launched, hoping to make political hay while the sun shone. The trials struggled to be modern stagings, but the fog of accusations, publicity, riots, and international debate turned the proceedings into prolonged “affairs,” where the old “disreputable” language reasserted itself.

Ferreting out what a particular person actually believed is often impossible and irrelevant. Since the Trump presidency, we easily grasp that there can be a shocking symbiosis between cynicism and credulity. Some of the people Teter writes about were both credulous and doubtful. At the end of the day, establishing the blood libeler’s true “position” is as complicated as brain surgery—more so, since, to date, no scholar has been able to explain why there was a three-hundred-year hiatus in these episodes or why the era of modern trials lasted only thirty years. Not even Teter establishes just how a largely uneducated populace made contact with the “memory trail” of written tradition that preserved and transmitted the blood libel.

In the absence of such a comprehensive account, historians do the best we can, accenting or downplaying this or that feature of each ritual-murder case. Scholars used to concentrate on the lurid, premodern religious aspects of these cases, but Kieval chooses a different path, offering elegantly written “thick descriptions” of the social and economic contexts of the five cases he investigates. He is formidable at laying out the questions, rumors, and innuendo that triggered a “successful” ritual murder allegation: the kinds of knife wounds and degree of exsanguination in the body, the proximity of Jews, the pointed animus of a few locals, etc. With such granular micro-history, Kieval clearly hopes to avoid one-dimensional arguments based on religion.

The details he gathers are indeed relevant and interesting, and no serious scholar would dispute that the blood libel and the violence it provoked were in part precipitated by the particulars of local political or personal conflict. It is gravely misleading, however, to suggest that charges of ritual murder can be understood mainly in terms of forensic, social, economic, and political conflict. Something else was going on, something that gave these cases their unique charge of emotion and irrationality. Historians cannot indulge in the luxury of the Skinnerian psychologist who focuses only on behavior, not the mind. We need to know something about why people in these places came to think as they did, and we cannot do that without examining the construction of their cultural identity.

So why the Jews? There is no simple answer. Many factors and levels of causation come into play in a blood-libel episode, but the attitudes and presuppositions of the actors are not unimportant. What was the origin of the longstanding social mentality that permitted someone at Tiszaeszlár to accuse a neighbor of a crime so heinous that no one would credit it for a moment if the alleged culprit were anyone but a Jew?

Obviously, a generalized “social imaginary” (or “anti-Judaism as tools for thought”) such as that brilliantly excavated by David Nirenberg in Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition does not explain or even prepare us for the shocking outbreak of a ritual-murder accusation. Then again, a general theory of class conflict cannot account for the outbreak of revolution in Russia in 1917, either. But that doesn’t mean that Karl Marx is irrelevant; it just means that the preconditions of events are not the same as their precipitants. The structures of social belief may nevertheless take explanatory precedence over the immediate triggers of ritual-murder cases. Longstanding biases about “the Jew” sneak in through the back door and affect behavior in ways that the accusers in these cases may not have been fully conscious of.

It is also crucial to note that the ancient force and ongoing presence of a religious mentality is not the same thing as formal religion—e.g. sermons attacking “Christ killers”—although there was plenty of that, including in the cases Kieval studies. Religion is the red thread connecting the ancient and the modern, from William of Norwich to Esther Solymosi of Tiszaeszlár.

It is a single mentality, variously developed and expressed. The people making the wild accusations of ritual murder while burning synagogues, desecrating Torahs, and attacking homes and individuals were not primarily arraigning Jews for their race, but for their alleged attachment to “diabolic” teachings in Judaism’s holy scriptures. The battle line the accusers drew was most often between Jews and Christians, not between Jews and Aryans or Germans.

Many participants were driven by extreme emotions—fear, anxiety, hatred—that needed no encouragement from theology or the clergy. As the German scholar Christoph Nonn has shown, the accusers wanted the chimera of ritual murder to be true; they were motivated not just by self-interest but also by a will to believe, a will with roots in hope and fear. This will to believe was the blood libel’s hidden strength, hard to pin down because it often went implied, and because those impelled by it did not leave records or give interviews attesting to it. That means that historians must often detect it indirectly. But if they overlook it, they miss something indispensable to a proper understanding of nineteenth-century blood-libel cases. These cases involved innumerable novelties and variations, as Kieval well documents. But for all their novelties, they were not an innovation—not an invented tradition, but a real one, stretching back many centuries. Jews had become the targets of many other kinds of accusation during all those years: social, economic, cultural, political, racial. But if ever proof were needed that the original and essentially religious charge of “devil” was still current, then the blood libel is it.

We tend to account for the recent upsurge of antisemitism in Western societies mainly in terms of global geopolitics and immigration trends. But explanations that restrict their view to Israeli–Palestinian relations or the presence of Muslim newcomers in wretched suburbs overlook another crucial factor: the complex meaning attached to the word “Jew” in Christian society.

That factor becomes clearer if we look at another episode in the same era as the ritual murder trials Kieval discusses. Timothy Verhoeven’s book Sexual Crime, Religion and Masculinity in fin-de-siècle France: The Flamidien Affair (2018) recounts a straightforward case of pederastic homicide. A Lasallian brother named Flamidien in Lille was accused of murdering a twelve-year-old pupil to keep him from talking about Flamidien’s sexual predations. The event amounts to a small fray in the ongoing clash between the French Republic and the Catholic Church; within a year it got swallowed up by the Dreyfus Affair. What is noteworthy about the episode is not the set-to between anticlericalism and Catholicism—a theme well known and studied—but rather that it never occurred to either side in this conflict to resort to medieval myths or apocalyptic calumnies. Indeed, the only moment of true craziness in this episode concerned the Jews, when a Catholic editor defending Flamidien speculated that a secret Jewish cabal was somehow behind the whole affair, taking revenge on the Church.

The kinds of accusations leveled at Jews would have been considered patently absurd had they been leveled at any other group. Only “the Jew” could be described as the origin of evil, the devil’s creature, the enemy of the nations, the drinker of Christian blood. No amount of archival ferreting out of the racial, economic, social, political, or cultural contributors to antisemitism will explain away its abiding anti-Judaic dimension. Scholars may wish that modern antisemitism were a purely secular matter, detached from the foundations of its medieval forerunner; yet only the deep religious past can explain this curiously non-ideological, non-“scientific” idea of the Jews as a diabolical menace. One notes something peculiar about violently anticlerical, racist antisemites, the kind who insisted that race, not religion, is the key. They often followed this up with “the only way to fight ‘the Jew’ is with another, greater spiritual conviction,” as Eugen Dühring put it. This is a wild contradiction unless we keep firmly in mind the underlying religious nature of Jew-hatred.

In sum, the secular doctrines and politics of the “new” antisemitism were by no means identical with the collective social understanding (the traditional anti-Judaism) on which they implicitly depended for their popular reception. How ritual-murder accusations were “heard” is a different matter from what the antisemites intended them to sound like. It was anti-Judaism’s lingering presuppositions that allowed antisemitic ideology to penetrate so deeply into modern European societies. The result was usually more than anyone bargained for.