I like walking the streets of New York. Sometimes I’ll head up through Greenpoint to the Newtown Creek, or follow the Hudson River as it wraps around the Financial District, or even wander through the halogen-brightened streets of Midtown. I especially like walking at night, when whole neighborhoods empty out, and windows illuminate otherwise obscured worlds: the art-bedecked brownstones, the silk-walled supper clubs, the pocket-sized bedrooms with their fairy lights and IKEA containers. Recently, I turned toward a bodega’s glass door and saw a cream-colored cat draped across an ATM, a drunk-looking man slowly running his fingers through its fur. You glimpse all these lives, and you are alone. You are presented with the vision of a bright, gleaming city, but at a distance.

Few artists have captured this sense as keenly as Edward Hopper. At a new exhibition of his New York work, I stood before painting after painting of bare apartments and deserted streets, and I felt like an outsider peering in through a cracked window. Even in the Whitney Museum’s bustling, booming exhibition halls, he made me feel completely alone.

Hopper was born just north of the city in 1882. At the turn of the twentieth century, he began taking the ferry down to Manhattan to study at the New York School of Art and Design, where he developed a breezy, impressionistic style. His figures blend into their environments or disappear into shadow, overtaken by the overwhelming geography of the metropolis. Only the sunlight seems capable of standing apart.

Between 1906 and 1910, Hopper spent several long periods in Paris, a city he described (in a letter to his mother) as “graceful and beautiful,” a stark contrast to New York’s “raw disorder.” One could see much of his career as an attempt to find Paris in New York, to discover some grace in all the chaos. His compositions became simpler, cleaner, and less populated. He trained his eye on stray figures crossing empty streets. The paintings achieve order, but at the price of loneliness.

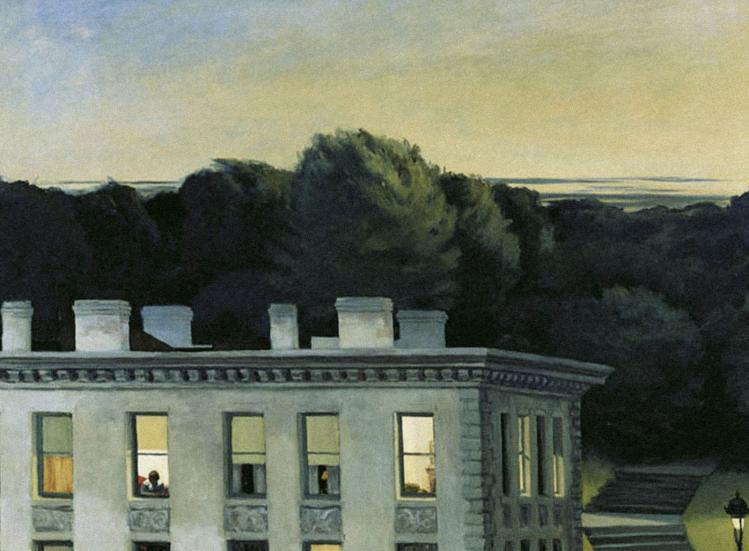

Hopper found his subjects by wandering throughout the city, tramping sidewalks and crossing bridges and peering down from elevated trains. He painted movie theaters and cheap cafeterias, apartment blocks and brownstones, Central Park and Washington Square and Prospect Park in all manner of light. Again and again I pulled up at 1935’s “House at Dusk,” a long rectangular composition showing an apartment building, a strip of trees, and a soft green sky paling into night. Hopper captures both the last pure evening light and the harsher glow burning in each apartment, drawing our attention to an armchair, a mantelpiece, and a woman leaning out a window, her head turned right, focused on some invisible street scene just below the frame. The effect is subtle, but in its way Hopper’s painting is as unsettling as anything by Magritte. The building is small, its residents even smaller, dwarfed by the sky and the surrounding city.

Hopper catches his subjects in private moments, with their backs turned and their eyes averted. His windows form a kind of invisible barrier, generating both intimacy and distance. Even when his viewpoint is from within the room, though, Hopper’s subjects might as well be on the other side of the city. There’s never the slightest suggestion they know they’re being looked at.

What Hopper saw was a city in stasis. His figures appear frozen, forever on the verge of motion—about to turn a page or press down on a piano key. His ushers and actors and café dwellers are always waiting for something, as if hoping the city itself might reach out and carry them forward. Even a bucking horse and the wake of a motorboat seem frozen in place, arrested in time. All paintings are still, but Hopper’s are stiller.

Hopper is often described as a painter of “alienation”—during my time at the Whitney, I even heard one man grumble the word from his bench. This exhibition certainly has its share of shuttered storefronts and lonesome café women, the kinds of images that by now have become visual shorthand for the estrangement of modern life. But his work also has a quiet warmth. His urban labyrinth is full of Vermeerian sunlight; his spare apartments are homey, at ease with their loneliness.

Part of the warmth and ease come from the recurring visage of a quiet, sharp-nosed blonde woman. In 1924, Hopper married the artist, actor, and designer Josephine Verstille Nivison. Edward and Jo lived together at 3 Washington Square North until their deaths, going to the movies, exploring the city, and painting side-by-side. Some of Jo’s watercolors—a potbellied stove; spectral Washington Square; Hopper, balding, at his easel—are displayed beside a portrait painted by her husband, showing her turned away, right arm raised, at work on her own.

Nivison’s image appears frequently in Hopper’s work—as a movie theater attendant, a burlesque dancer, a comedian, a waitress, and as one of the many still women gazing mutely from their apartment windows. One senses that Hopper sought to fill the city with her likeness, to situate her in every hired room, every park, every office, as if to make the city livable by giving it the shape of their own private life. You sense that for Hopper, the geometry of a city is also that of a room, and that one person might easily stand in for a million others.

This might strike you as a somewhat cramped vision. But New York City is like that even now, and your New York will often conform to the contours of your life. You see the same strangers on the same subway lines, come to recognize panhandlers, identify the guy selling incense between stations by the sound of his voice. A whole neighborhood can be irradiated by the ending of a relationship. I once ran into a college acquaintance as she was leaving the restroom at McCarren Park. We chatted as if it had been just a few days, not a decade, since we had last seen each other. Then she went her way and I went mine. There are as many New Yorks as there are New Yorkers, and despite all the anonymous crowds, each of these New Yorks includes pockets of familiarity and solitude.

The Whitney’s faintly hectoring signage insists, again and again, that Hopper’s paintings do not describe any “real” New York; instead, they present the New York of his dreams and memories. His city seems to have the population of a small village (with an entirely white population). His late paintings no longer depict any recognizable place, drawing instead on a store of stock images: bedrooms, cafés, cavernous corner offices. Yet looking at a painting like New York Movie, I see a New York I know well, albeit one wearing a vintage outfit. Jo’s usher could easily be thousands of workers all across the city right now: grocery-store clerks, overnight doormen, bouncers, delivery drivers sitting astride their e-bikes, gallery attendants staring at their phones. Or she could be any one of the people who seem just to be killing time as they walk past bustling restaurants and foggy bars. This is still a city of people forever on the verge, always about to be doing something, always expecting something more.