It was a morning of stark contrasts: giggling ten-year-old school kids filing into the modern chapel built on the site of the old Emperor Wilhelm Memorial Church, which was almost completely destroyed during the Allied bombing of Berlin in 1943. A bit of the old church tower and apse still stand and have been carefully preserved over the years, an icon not only to Berliners but to all Germans. It is known as the “Gedächtniskirche,” or the “memory church.” The memory it preserves is not that of the emperor but of war itself.

Before unification in 1990, it was the Berlin landmark, at least for West Berliners. The famed Brandenburg Gate had been incorporated into a portion of the Berlin Wall; the Reichstagsgebäude (the Wilhelminian-era parliament building) was still a leaky half-ruin on the very edge of the divided city, housing a history exhibit on German militarism. And the impressive East German TV Tower (Fernsehturm) was in any case a latecomer to the cityscape. It debuted in 1969, and was in those days more a fixture of Cold War competition. It was meant not only to look stunningly graceful, a gleaming credit to the still young German Democratic Republic (GDR), but also to jam the anti-communist broadcasts of RIAS (Radio in the American Sector) emanating from West Berlin and until that point making their way without interference into the heart of the GDR.

The school kids, from the nearby Jesuit Canisius-Kolleg, radiated joy as they poured into the chapel that morning at 8:30 precisely. Though not quite a holiday, it was at least free of instruction. Apparently, even an Ash Wednesday prayer service was reason enough for a little giddiness. Their laughter and banter lit up that dreary Berlin morning, less a reminder of our mortality—the Ash Wednesday messaging had blessedly not quite reached them—than a testament to undying Easter joy.

Pater Marco Mohr, SJ, rector of the Jesuit community and president of the school, had his hands full, as anyone would who is charged with preaching an Ash Wednesday sermon to an ebullient school group. On the other hand, these Berlin students are in some ways closer to Lenten suffering than many others. The esplanade they crossed on their approach to the service was the site of the 2016 Christmas market terrorist attack, the reason the area is now ringed by heavy-duty barriers meant to impede another such assault.

After Poland, Germany has taken in more Ukrainian refugees than any other country. As of late February, they number about 1.2 million (figures vary, in part because Ukrainians can enter Germany without registering, and some have returned). Ukrainians are now Germany’s largest refugee group, exceeding even the then-historic influx of about one million who came to Germany in 2015–16 in the wake of the Syrian civil war. The anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and, prior to that, the earthquake in Turkey and Syria, have understandably been grabbing the headlines lately. Less commented upon is the ongoing challenge of providing for so many refugees.

This is no abstraction to these Berlin students from Canisius-Kolleg, some of whom are refugees themselves. Unlike other schools that either refused to accept refugees in 2015, or did so only under duress, the Canisius-Kolleg opened its doors early in the crisis. The rector at the time, Fr. Tobias Zimmermann, SJ, made it a central mission question: If we don’t do this, he asked, why even continue on? Not all parents (or teachers, for that matter) were equally enthusiastic. Some were worried about foreigners diluting the quality and status of this highly respected school. Would the refugees be up to it? Do they really fit the profile of an ambitious Gymnasium (college preparatory school)? If they can’t speak proper German, how can they possibly keep up with the demanding coursework?

Undaunted, Zimmermann and his successor Mohr petitioned the Berlin school authorities for special licensing and funding that would allow them to retool and formally expand their mission beyond the elite Gymnasium curriculum. They succeeded, and several years ago opened an “Integrierte Sekundarschule,” a more flexible secondary school they’ve named the Arrupe Zweig, in honor of Pedro Arrupe, the long-serving Superior General of the Society of Jesus (from 1965 to 1983), who placed social justice at the heart of the Jesuit mission. Formally, this new wing is open to foreign students of diverse backgrounds, but it was founded principally to accommodate refugees and that remains its primary mission. The point is not to create an isolated parallel educational stream, but rather to provide for as much crossover as possible, allowing some pupils to integrate into the Gymnasium proper and encouraging “traditional” students to interact with the newcomers.

It is not perfect. The school leaders here view it more as a work in progress than a model program, but in some respects they are too modest. School assessment authorities reviewed the program recently and marveled at the acquisition rate of German language among the refugees. But there is also heartbreak whenever a student fails to make the grade. And that happens too, for a variety of reasons.

All of which made me wonder if I had too readily fastened upon the students’ joy that morning. I am after all an outsider, seeing perhaps what I most want to see. Savoring their jocular, teasing exchanges, I of course don’t hear those other stories of discrimination, deportation, and despair.

Pater Mohr is more attuned to the darker side, and he invokes that, oh so gently, in his sermon. Somehow finding the right words, he addresses the war in Ukraine, the earthquakes in Turkey and Syria, and the climate crisis. It breaks my heart that kids this age need to be concerned with these heavy issues. Mohr is wiser: he knows that these are not elective “issues” to them, but rather unavoidable realities.

Even to fairly well-off Berliners, the energy crisis was brought home by the sudden interruption in the flow of Russian gas and oil earlier in the year. And even those without relatives shivering in the cold Ukrainian winter will have some inkling of the changed situation. Churches are no longer heated here (and attendance is even lower than usual), and when you go to the public pools, you are now asked not to let the shower run on the automatic timer, but to turn it off manually. Every little bit helps keep Germans independent of Russian gas.

Germans were in the news recently for their “failure” to provide Leopard-2 tanks in a timely fashion. The eminent historian of Germany Timothy Garton Ash invented a new German verb to pillory Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s trademark hesitation and delay before finally giving in to what political observers thought inevitable from the outset. The verb, appropriately, is “scholzen.”

But in Germany, Scholz’s hesitation resonates, and is far more widespread than Ash’s neologism implies. While there is substantial support for Ukraine in general, when it comes to providing attack tanks, that support drops to just over 40 percent.

That figure jumped by about 10 points once the chancellor made the announcement, but a widespread sense of threat (almost 50 percent) and hesitation to provide further arms (35 percent) persist, as new data reported by the respected weekly Die Zeit documents. The war is simply a lot more real to Germans: Kyiv is about as far from Berlin as are cities like Freiburg in southern Germany. And the concern—as some opposed to further military aid to Ukraine have openly admitted—is that Russia will punish Germany by placing it in its crosshairs.

Which is precisely why others think Germans need to step up and lead in a more decisive manner. It’s time to act like the country it is: Europe’s richest and most populous.

Yet doing so would defy central tenets of Germany’s postwar political culture, one the United States rather insistently fashioned. West Germany was after all a vassal (or, to put it slightly more politely, client) state until it joined NATO in 1955, and even then wasn’t officially and fully independent until unification in 1990. The joint entry of East and West Germany into the United Nations in 1973 was meaningful symbolically, but also a bit of window dressing, suggesting to many that both countries were more independent than they actually were.

It is now popular (and my students at the University of Notre Dame eagerly join the chorus) to demand that Germany actually spend the 2 percent of its GDP on defense that it committed to under the George W. Bush administration. Many of these students seem to think this call was new with Donald Trump, and it is their effort, I suspect, to salvage a remnant of that president’s persistent tirade against Germany and its then chancellor, Angela Merkel. During the Trump years, Germans feared the United States more than Russia or China by a large margin, and awarded the president the lowest popularity rating—9 percent—ever measured in postwar history.

I had always been quick to urge my students to view “defense” more broadly, to consider, for example, the huge expense entailed in hosting millions of refugees, the first wave of which came to Europe in part due to the failed war in Iraq and the prolonged and botched occupation of Afghanistan. (Some scholars estimate Germany’s refugee hosting, broadly construed, costs in the neighborhood of €30,000 per refugee per year.) And as long as there was a U.S. president in power who openly cast doubt on America’s Article 5 obligations under the NATO treaty, why should Germany rush to fulfill its obligation?

But the world has changed since then. It is not just Biden and Blinken at the helm that has reassured our NATO allies. More than anything, it was Putin who caused the sea-change in German thinking. Within just three days of the invasion, Scholz, whose own Social Democrats had notoriously dragged their feet when it came to armaments and defense readiness, announced a €100 billion investment in Germany’s embarrassingly outmoded military. This posture is referred to here as a “Zeitenwende,” a new era in German political culture, a term that echoes the radical rupture in German history constituted by unification (die Wende) in 1989–90.

Up until now, Germany had determined never to send military materiel into active war zones; its own troops, such as they are, have been essentially confined to peacekeeping missions in conjunction with the UN or NATO. Yet when we criticize Germany as a defense “freeloader,” we should probably keep in mind that this is exactly what the United States wanted and demanded for most of the postwar period. NATO placed nuclear weapons in Germany, but they were never under German control. A condition for permitting German unification—one insisted upon above all by the French and British—was precisely that Germany not flex a military muscle of any kind, indeed that it remain fully subordinate. Helmut Kohl needed to sacrifice the beloved Deutsche Mark and substitute the Euro as a gesture of European integration. The fear then—just a generation ago—was of German strength and self-assertion. Within a fairly short period of time, Germany’s posture of subordination would come to be seen as that of a shirker unwilling to pay its fair share of defense or to take the lead in European affairs.

When Scholz hems and haws, then, he is not just scholzing. On the contrary, he is responding to a deeply conflicted political culture that frankly does not change course on a dime. Yes, the war in Ukraine has been going on now for more than a year. But even such irrefutable and upsetting evidence of aggression cannot reverse decades of “lessons” that were deeply inculcated in the Germans. Accompanying support for Ukraine, calls for greater diplomacy are on the rise.

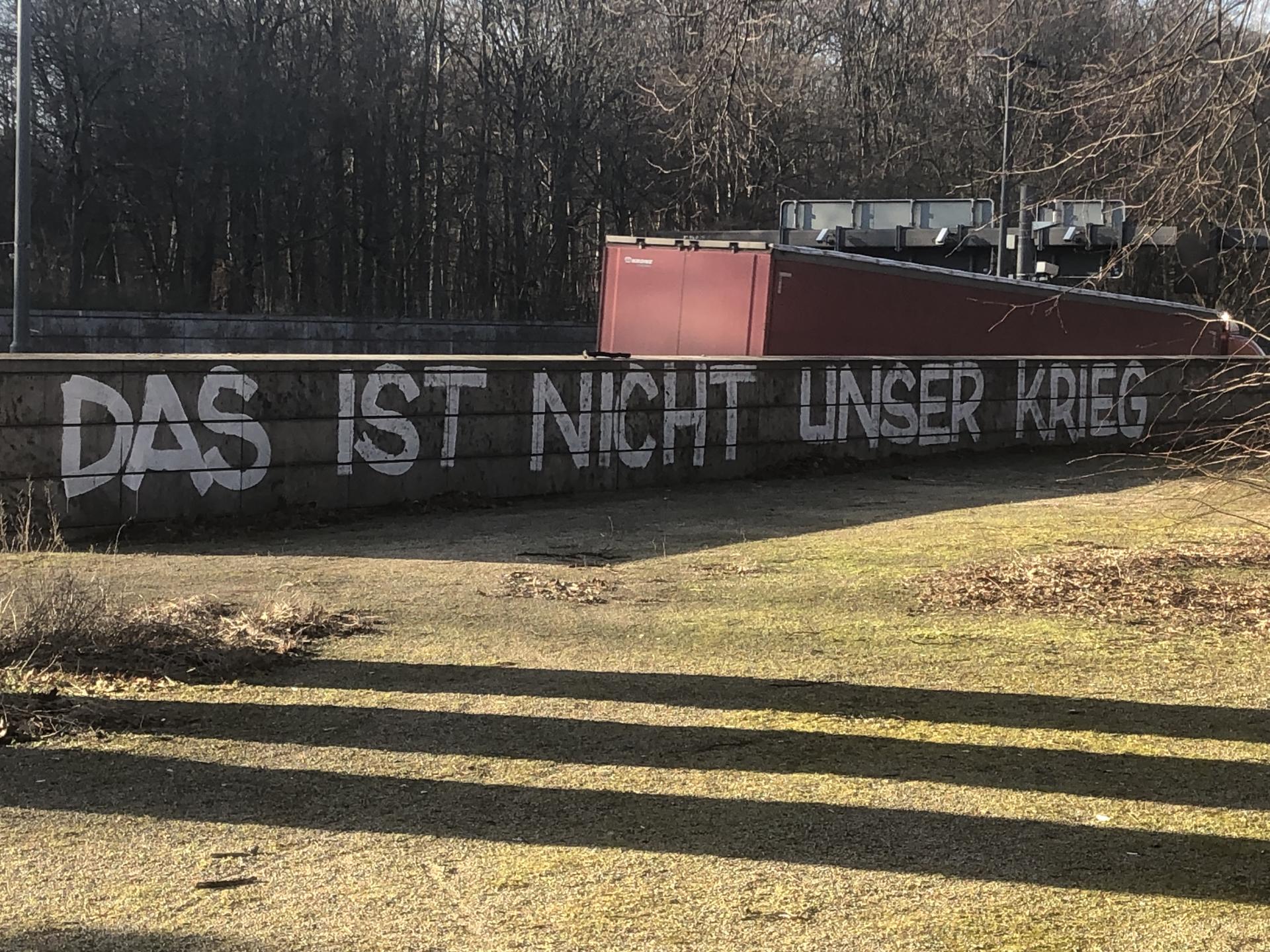

The chief lesson of World War II—made famous by the Käthe Kollwitz sketch of the young man screaming “Never again war” (“Nie wieder Krieg!”)—was of course pacifism, at least for Germans, and for the foreseeable future. Their military history is just too tainted, the thinking goes, ever to allow them to participate again. Abstinence is both a virtue and a requirement (all too convenient, politically and economically, some critics would say), a feeling that fueled a lot of the opposition to providing the Leopard-2 tanks to Ukraine. “Imagine,” I’ve heard a number of Germans say, “a German-made tank once again moving against the Russians!” The sentence is spoken as if it is a self-evident rationale for withholding the tanks.

Now the same sentiment is being marshaled against the proposal to send fighter jets to Ukraine. I find myself growing impatient, wanting to blurt out: What if the Allies had responded with such nonsense during Hitler’s wars of aggression? Why can’t Germany just finally step up and lead?

But then I think of those students at the Ash Wednesday service and feel called to a little more compassion. On the way to the service, one group asked their teacher excitedly: “Are we going to that big bombed-out church? Wow!” These monuments to destruction have indeed left their mark on the German psyche. They represent powerful cautionary tales in the form of dramatic public exhibits. And the invasion of Ukraine, far from making it immediately clear why Germany should provide arms, has in not a few cases stirred deeply disturbing memories among those who came of age in the decades after the war, kids who grew up among mounds of rocks and half-ruined buildings that persisted well into the 1970s (in West Germany) and to the bitter end (in East Germany). No Zeitenwende can erase these deeply ingrained scars, certainly not overnight.

Yet the lingering “German doubt” (to quote one of the leading papers here) is not just a Cold War artifact, but something equally attributable to the Trump presidency, when Germans first learned (on a broad scale) to question the U.S. commitment to defend Europe. No one doubts that Biden is a staunch promoter of NATO, but who will succeed him? If it is Trump, or another Trumpian isolationist, that would leave Germany uniquely exposed. Many Germans are watching American politics closely, and they’re worried.

Generations of postwar Germans have been socialized to learn that the Second World War meant that they were never again to lay hands on a weapon, or if so, only under NATO leadership, embedded within an American-led alliance in which Germans follow but pointedly do not lead. For decades, we’ve expected Germans to show repentance, remorse, and reticence—and understandably so. The Kaiser Wilhelm “memory church” that we gathered in to celebrate the beginning of the Lenten season of renewal merges with the larger “memory culture” (Erinnerungskultur) carefully cultivated over decades to confront the Holocaust. Yet how does one combine that required lesson, indelibly imposed on generations, with this new expectation to arm, intervene, and orchestrate military action? Scholz, for all his infelicities, may have it right after all. In all of his scholzing, he’s honoring both the demands of the present and the calls of the past. He may even be the man of the moment for contemporary Germany.